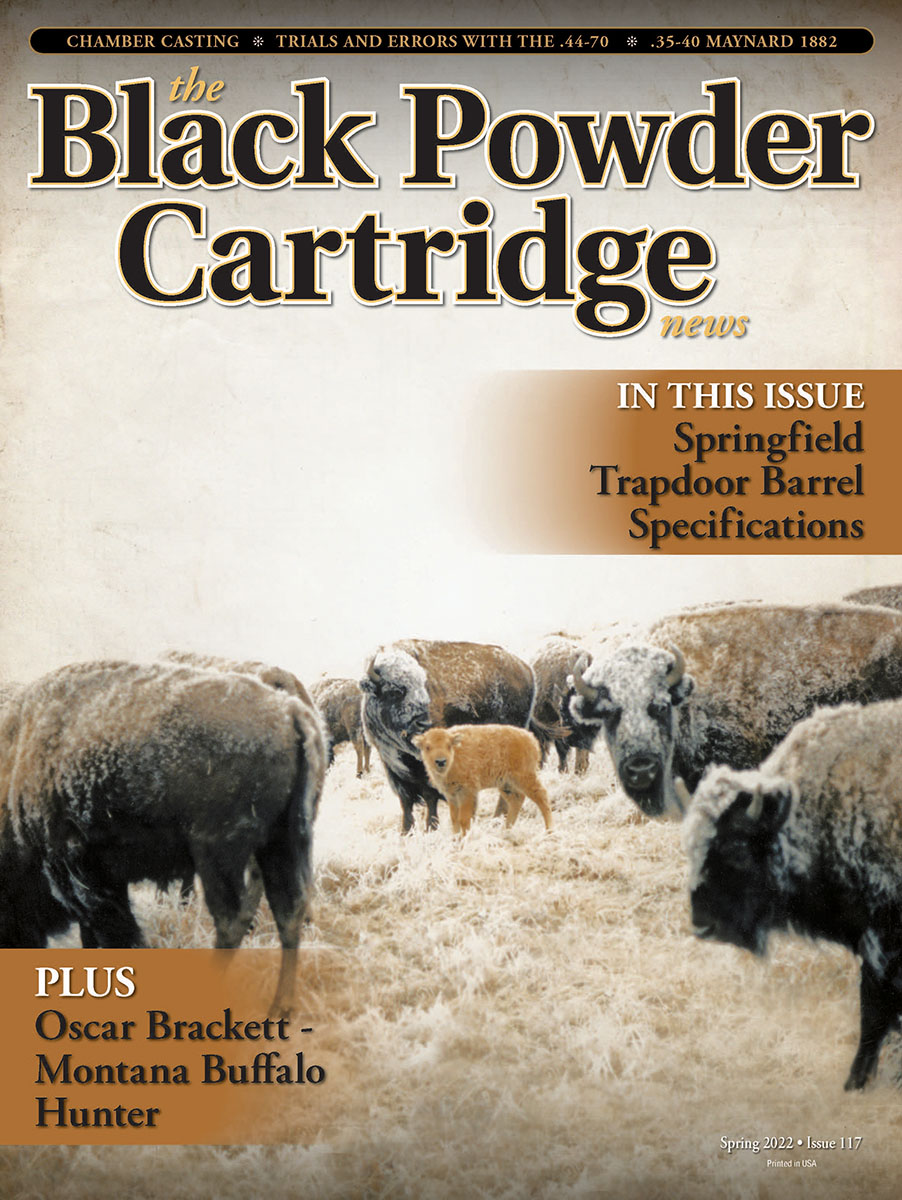

Oscar Brackett

A Montana Pioneer and Buffalo Hunter

feature By: Leo J. Remiger | March, 22

Brackett had been born in East Corinth, Maine, in 1850; made his way west and by 1872, he had arrived at what he called “Moorhead, North Dakota.” (In 1908, Brackett mentioned he arrived in Moorhead, North Dakota, in an article written about him that appeared in The Ismay, the local newspaper of Ismay, Montana.) As Minnesota became a state in 1858, and the city of Moorhead, Minnesota, was platted in 1871, that is unlikely. Moorhead was incorporated in 1881 and was named after William Galloway Moorhead, an official of the Northern Pacific Railway.

Moorhead is bordered on the west by the Red River of the North and Fargo, North Dakota. Fargo was platted in 1871, as well and incorporated in 1874. Fargo, North Dakota, was named after William G. Fargo who was one of the directors of the Northern Pacific Railroad as well as one of the founders of the Wells-Fargo Express Company.

Being they are considered “Twin Cities,” only separated by the Red River, it’s easy to see how both of them could have been considered either Moorhead or Fargo in 1872. Especially when leaping back 36 years in memory like Oscar Brackett was doing during his interview for the original article:

“I was born in old Maine in 1850, and was only a young man of 22 when I got my first experience. It was when the Northern Pacific railroad was being built through the Dakotas and I first landed at Moorhead, North Dakota. I got the stage at Moorhead for Valley City – which was only a railroad grading camp then. Here I found employment in a railroad supply store and remained all summer. This gave me an opportunity to look around a little and get my bearings. It was all new to me – this big western country. At that time they were building the Northern Pacific railroad through to Bismarck. The road was started the year before and was built as far as Moorhead.”

His cousin, George A. Brackett, was one of four contractors building “the road” through to Bismarck. The three other contractors were Messrs. Morrison, King and Pillsbury. They operated out of Minneapolis. Supplies were hauled out from “end of track” to the various supply stations by ox team. Brackett mentions the supply trains consisted of 20 to 30 teams per train. While at Valley City, Brackett described a visitation by grasshoppers:

“At Valley City that summer was the first and only time I saw a visitation of grasshoppers. They came on afternoon about three o’clock and settled down a regular black cloud over everything. They left the next morning about 9 o’clock, but they had eaten up every green thing in sight – including the leaves on the trees. You couldn’t walk without crunching them under your feet. It was awful. The railroad campers had a fine garden and the hoppers left nothing of it but bare ground. The ground was literally covered with them.”

That fall, Brackett returned to Minneapolis and spent the winter working in a pork packing house. In the spring of 1873, he traveled back to Bismarck and found employment with Prescott & Bly at their sawmill. The steam-powered sawmill was located six miles below Bismarck on the river, near the mouth of Apple Creek. The majority of the lumber cut was cottonwood. In the fall of 1873, they relocated the sawmill and Brackett remained that winter to look after the lumber, and at the same time, cook for the camp of Daniel Manning. Manning’s outfit hauled lumber from another sawmill to Bismarck with what they called a “4-bull team.”

In the spring of 1874, Brackett ran a wood yard, located near the old mill site and supplied steamboats on the river. In the fall and winter of 1874, Brackett teamed up with a man named Andrew Collins and became a market hunter. They killed deer and elk in the Big Timber bottoms along the Missouri river.

In the spring of 1875, Brackett worked for a man named Oscar Ward, approximately six miles from Bismarck, he did not detail what the job consisted of.

News of gold in the Black Hills fired up the local population and Brackett caught the fever just like the rest:

“I got the fever just the same as the rest. That winter we made up a party of about 30 – mostly Bismarck boys and men. We had ten teams. We did not dare leave in a body, so we pulled out, a team and a few men at a time. We met at a point on the Hart river, about 30 miles from Bismarck. This was about the 10th of December. We crossed the Missouri river on the ice. There was a good deal of snow on the ground near the river and in the valley, but a couple of days’ travel took us out of the snow and for the rest of the way we had fine wheeling clear to the Black Hills.

“Every night we stood guard over our horses for fear the Indians would come and run them off, but we saw no Indians until we reached the Hills. The first night after reaching the Hills we camped not far from Crook City at Bare Butte. We did not go into the hills then, but bore off to the left and followed the edge of the hills for a day’s travel and went in on the Custer trail. The day after we left Bare Butte, while crossing over a spur of the hills that run away out into the prairie we saw what we took to be soldiers out on the prairie. As we stood looking at them we saw a lot of Indians moving through the oak timber that grew near the foothills and a little beyond the first lot was another party. Then we discovered that what we had taken for soldiers out on the prairie was a big body of Indians. They were traveling. Shortly after, a couple of Indians came up the road directly behind us. We didn’t want to get too close, so we fired a couple of shots over their heads. They ducked down behind their ponies and went back over the hill on the run. And it wasn’t very long after this until there seemed to be Indians all around us. We were all well armed with good guns and opened fire and had quite a battle, but I guess nobody was killed on either side.

“We drove down off the hill or spur and got into the prairie and kept going. One Indian got into the road behind us and as we were going up a little rise of ground he shot into the train, but it was at very long range. We had an old buffalo hunter by the name of Dick Stone in the party who had a big buffalo gun with a telescope sight. He went over the hill and laid for the Indian. When the latter poked up his head Dick shot at him and the bullet tore up the ground in front of where he lay. It was too close for the Indian. He dug out and went away out on the prairie to the windward of us and the rascal set the grass on fire.

“The grass was heavy and tall and burned very fast. It looked pretty ugly for a little time, but before it reached us we set a back fire and drove on to the burned ground. We finally drove on and camped that night on the top of a square butte. We made a corral of our wagons and tied our horses inside and dug holes for our beds on the outside of the corral, throwing up the dirt for a sort of breastworks, thinking sure we would have a night attack. But their medicine was poor and they quit us.

“One of our boys on this trip was Henry Dion, now a well-known and prosperous business man of Glendive. He had a partner named Isadore and a team of very slow mules. After the fight began Isadore was very excited and scared nearly to death. He would dance about the team and wagon and yell frantically “Whipperde mules, Henry! Whipperde mules, Henry!” I guess Henry never heard the last of Isadore’s “Whipperde de mules!” I know Isadore dug his hole good and deep and crawled into it and he wouldn’t come out to stand guard or anything else. Henry couldn’t have pulled him out of that hole with the old mule team.

“The next morning was New Year’s Day. We went on into the Hills and camped in a beautiful park. The next day we made only a short drive and went into camp. It snowed that night and we laid over the next day and took a deer hunt. Anybody that could shoot at all brought in a deer that night. The next day we went on over to Rapid Creek and most of us took up placer claims. But they didn’t amount to anything.

“That winter, however, there were some rich strikes made up on Deadwood Creek and there was a grand rush up there. I went over there in the spring, 1876. Deadwood was full of people. Lots of them were dead broke, too, and couldn’t find work or grub. About that time – after I had been at Deadwood awhile – the Custer massacre took place. I had got about all of the Black Hills I wanted, too, though I had not seen much of the gold. So along about August I left there. Joseph Penwell of Bismarck was in with a lot of freight teams and I went out with him. The very first night out the Indians attacked us and tried to stampede our horses. They did not succeed, however, as we saw them before dark and was on the lookout for them. They shot one of our men, Frank Figge, through the foot. The next morning we put the wounded man in one of the wagons and pulled out. We hadn’t gone more than a mile or two when the Indians showed up again and began firing into us. Two of the Indians were in the road behind us blazing away at us. Penwell and myself went back a little and laid behind a little hill and let the train go on, but with instructions not to go far enough so that Indians could cut us off from them. At the crack of our guns one of their ponies threw down his head and began to turn around and tried to lay down, but Mr. Indian played the quirt to him and got behind a hill. We missed the Indian but his horse was killed. After that they let us alone.

“The third day out we came to a creek in the afternoon. There we saw a wagon standing on the bank. Coming up two men crawled out from under the wagon, and off a little ways was a dead man. They had camped there the night before on their way to the Hills. Early in the morning a band of Indians came down the creek. The men tried to motion them not to come in close, when the Indians fired on them and killed one. The others got behind their wagon and succeeded in killing one of the Indians and standing the rest off. They had a yoke of oxen picketed out in a low place where the Indians had not seen them. They had filled some sacks with sand, put them under the wagons and got in behind them for breastworks and waited until we came. We took the dead man back about ten miles to another creek and buried him. We trailed their wagon and drove the oxen back to Bismarck...

“Oscar Ward, now a well-known business man of Bismarck, was one of our party. He started to the Hills after our party went the winter before. Andrew Collins, the man I used to hunt with on the Missouri bottoms and a fine shot, and about thirty others had gone in together. He and Collins had quite a bunch of milch cows they were taking to the Hills. At the Meadows the Indians came one night and drove all the cattle away. In the morning Ward, Collins, and Ward’s brother, Henry, and ten or twelve others took their trail and came up with them. The cattle were grazing on a little flat. They rode up to the cattle and were about to drive them off when the Indians showed up and surrounded them. They had one of the hardest fights that ever took place around the hills. Ward’s brother was shot and killed and Collins was shot through the knees. He fell and thought his leg was broken, but the shot just grazed the bone above the knee cap. They killed a number of Indians and stood the rest off. On the start, some of Ward’s party ran away and that give the Indians courage. They rode up and shot one of Ward’s party in the back with an arrow. He fell off his horse and then did some good fighting. Those who ran away got back to camp and reported the rest all killed. Those who stayed with the cattle finally drove the Indians off, but had to leave the cattle to bring in their dead and injured…”

The government established Fort Keogh near Miles City.1 The hay and wood contract for the new post was let to McLean & McNiter of Bismarck. When Brackett got back to Bismarck, the firm was fitting out a lot of teams and men to go up to Fort Keogh and put in hay and wood for the use of the troops there. Brackett joined the party and they traveled up the east side of the Missouri to Fort Buford where they took a big government boat and went up the river to a place called Fort Union. There, they took their wagons and supplies and the men across the Missouri in the boat, swimming the horses over. Fort Union was just above the mouth of the Yellowstone River. There, they were joined by government troops who escorted them to Fort Keogh.

After they arrived at the mouth of the Tongue River, near where Miles City now stands, they camped on the east side and the troops camped on the west side of the stream. They built some temporary barracks and remained in these until the fort was pretty well under way. The materials for the new fort were shipped up the river by steamboats the next spring and summer. There wasn’t any hay on the ground, so they had to start in on the wood. The firm filled their contract with all dry wood. They were not allowed to cut any green timber. A few years before there had been a very hard winter with much deep snow and the Indians had cut down most of the green cottonwoods to feed their ponies. The Indian ponies would eat the bark off the limbs and eat the small twigs just like a lot of beavers. Brackett mentioned it must have been a very deep snow as many of the stumps, where they had cut the trees down, were up six or seven feet from the ground.

Brackett also mentioned:

“About the first of December the buffalos had begun to come in from the north on the head of Sunday creek. I heard all sorts of stories of how plentiful they were, and as I was pretty well tired of the wood-cutting, Archie McMurry, Bill Hook and myself took our ponies, loaded them up with supplies and started up Sunday Creek. We were going to make our fortunes poisoning wolves. We traveled all one day and until nearly night the next before we saw any buffalo. But we came to them at last and there were hundreds of them in sight just ahead of us up the creek. We went into camp for the night and in the morning moved up the creek a short distance. When we were packing up we heard some shooting, but thought it must be a party of wolfers.

“After we had made camp again McMurray and Hook went out to get meat and put out some poison. I remained in camp to watch the horses. The boys didn’t come back until dark. When they did get in the first thing they said was, “We’ve got to get out of here. The country is full of Indians.” They shot one buffalo. It ran over the hill and fell. At the same time the Indians were shooting into the same bunch. The boys backed out and got into a deep gulch and lay hidden all day. The next morning we were packed up and on the go by daylight. We traveled all day and at night reached Little Porcupine Creek about two miles from the Yellowstone. When we got down to the Yellowstone we camped under a big cottonwood tree. Someone had camped under the big tree before us and the tree was blazed and written on it was the names of two Johnsons and one Jackson. One of them was Jack Johnson, our ex-sheriff, and the other was George Johnson, one of Gen. Miles’ scouts. The latter was drowned the next summer while swimming the Missouri River. The third was Pete Jackson, afterwards my partner and who now lives at the mouth of Little Porcupine.

“We went out to a little island in the Yellowstone just above the mouth of little Porcupine and built us a cabin. There were no buffalos up to that time on the Yellowstone. The morning after we had our cabin finished it turned very cold. I went out so I could see up and down the bottoms and the buffalos were coming down the bluffs by the hundreds and the bottoms seemed to be covered with them. From that time until spring the country was full of them on the north side of the river, but they did not cross the Yellowstone. We only killed what we wanted for meat and wolf bait. We got only about a hundred wolves, but they were big ones. The two Johnsons and Pete Jackson with a couple of others got about 1,500 wolves that winter. They took big circles and put out lots of poison.

“At that time the wolves went in big droves and followed the buffalo up. It was a common thing to poison forty or fifty wolves at one bait. We got thirty-four all at one time. Those days it was easy to poison wolves, but now it is very hard to get them. The poison doesn’t seem to affect them.

“I remained at the cabin until the river broke up. McMurray and Hook went up the river and I have never seen them since. I rafted my outfit and hides down the river to old Milestown. I joined Pete Jackson there and trapped beaver down the Yellowstone. The country was wild – not a house from Miles to Buford, except at Glendive. There were a few soldiers there. We didn’t see a soul in the two months that we were trapping, except at Glendive. A few days before we quit trapping a couple of scouts came up the river and told us that the Seventh cavalry was coming up and the steamer “Far West” was coming along with forage for them.

“So we made camp close to the river and killed four antelopes and a deer and hung them up close to the bank so they could see them from the boat. We expected they would want meat and take us aboard. When the boat came along it tied up for the night right near the camp. I saw the captain of the boat and told him he could have the antelope and deer if he could take us to Miles. He said he could not take us. Shortly after, the cavalry came along and we sold the meat to the soldiers, except one nice quarter. I sent that to the commanding officer with my compliments.

“After supper I took a stroll over to his tent and asked him if he could not get us up on the boat – telling him the captain wouldn’t take us. He said, “Yes, you go right down and put your stuff on the boat. Need not say a word to the captain. I am running that boat.” So we were all right. We had sold our meat and got a free ride to Miles on the boat.

“We caught sixty beavers on that trip. We gave the captain two nice hides to make his little girl a cloak. After going back to Miles I started a wood yard on the river just above Buffalo Rapids and sold wood to the steamboats that spring. That was in 1877. A little later I put up hay and sold it to the government for use at the Fort. I got $20.00 per ton. That fall Pete Jackson and I went up to Little Porcupine and killed buffalo and rafted the meat down the river to the Fort and Milestown. The buffalos came south earlier that fall.

“After the river froze up Pete and I built us a large smokehouse and cured and smoked buffalo hams. We got a fine lot of meat. The fall before there had been some parties who shipped vegetables down from the settled valleys of the Upper Yellowstone in big flat boats. In the spring of 1878 I bought one of these boats, loaded on my smoked meat and went down the river. Besides the meat I had seven passengers. When we got to the Indian Agency at Berthall I sold my meat to the agent and then kept on down the river to Bismarck. When we unloaded our stuff from the boat I found a small buffalo ham which had been overlooked. I was on my way to my old home in East Corinth, Maine, so I wrapped the ham up and took it in my trunk and carried it along. On opening it we found it had kept nicely. I divided it up among my neighbors.

“After I had made my visit I came back to Bismarck. At that time Senator Dorsey and the Star Route mail contractors were fitting out men and teams to establish a mail route from Bismarck to Fort Keogh. Joseph Penwell, the man I had made the trip from the Black Hills to Bismarck with, was among the mail route outfit. I threw in with them and came along. The route followed up Hart River, crossed the Little Missouri just above where the Northern Pacific road now crosses. From there it ran to Fallon Creek Crossing, where the town of Ismay now stands; thence to the mouth of Powder River and then up the Yellowstone to Fort Keogh.

“Stopping places where they could feed and change horses were put in about every twenty miles. I was not feeling well and stopped at the second station out from Bismarck. Here I did the cooking and looked after the stage horses. While I was there one day I saw a large party of men on horseback and with teams coming. When they came up the first man I met was my cousin, George A. Brackett. With the party was General Rosser, chief engineer of the Northern Pacific construction outfit and a lot of officials. They had a government escort and were going through to the Yellowstone to look out a route for the Northern Pacific road. George was a good deal surprised to find me out forty miles in an Indian country, all alone. I guess I was a little foolhardy in those days, but I came out all right.

“I only remained there a short time and they sent a man out to take charge of the station and I took the stage and came on to a station twenty miles west of the Little Missouri called Lake Station. I stayed there for eighteen months. There were lots of antelopes and deer in there and I nearly kept the stage line in meat and made good money.

“In the fall of 1879 the buffalo came south early. A large band of them, a good many thousands, swam the Yellowstone river near the mouth of Powder and went in on the head of the Little Missouri and Grand rivers. The buffalo never remained in the Yellowstone valley summers, but always went further north each spring. The winter of 1880 I wintered on Alfalfa creek and hunted small game. In the spring of 1881 George McCone, now state senator from Dawson county, went to Bismarck where we bought us a fine team and went out on the head of Hart River and put in a big garden. The Northern Pacific was building their road through that country then. The government troops were there guarding the work and we sold our vegetables to the troops. We didn’t do any irrigating, but raised some good stuff.

“The next winter, 1881-82, I went up on Sandstone Creek, a branch of Fallon Creek, and killed buffalo for their hides. I killed about 700 buffalo that winter and sold the hides to A.C. Gifford, now a well-known resident of Fallon. He paid me $3.25 each for robe hides and $1.25 each for the bull hides. While the fur was good in the winter we never killed anything but cows and young buffalo. After about March 1st we only killed the big bulls. Their hides were tanned for leather. I camped by a big butte and this is now known as Brackett’s Butte.

“Up to that year there had been no market for buffalo skins. After they began to buy them everybody in the country went to killing buffalo. Some men did nothing but shoot them down and had men hired to do the skinning. Some of these hunters killed as many as two thousand in a winter.

“The next winter I went over on the head of Grand River and hunted. I got about 700 head that winter and sold my hides to Phil Brandenberg in the spring. He was one of the first settlers in Miles. The hides were hauled to Sully Springs, about ten miles east of the Little Missouri crossing of the N.P. road. That was the last year of my buffalo hunting.

“In the spring of 1883 I went into the sheep business and stayed with it until the hard winter of 1886-7. We had 7,000 head of sheep at the opening of that winter and came out in the spring with less than 2,400 head.

“About 1883 they began to stock the country up with cattle and sheep. Before this time there was nothing doing except buffalo hunting, wolfing, getting in wood and hay at Fort Keogh and keeping wood yards along the river to supply the steamboats. There were lots of boats coming up the river in those days, and the wood yard business wasn’t a bad one.

“During 1883 to 1887 the big stock men from the south began to ship in trainload after trainload of cattle besides driving them up across the country from the south in big bands. The country was simply overstocked. The winter of 1886-87 was the hardest on stock ever known since it was settled up. Most of the big cattle outfits came out of it with only about 15 percent of their stock alive, and these were mostly big steers.

“Since then I have been in the horse and cattle business mostly, except one year I spent in Alaska. I didn’t like that country. I came back to Custer county pretty well broke and have built up my ranch and home and stock business since.”

Oscar Brackett settled on the bank of Whitney Creek, some 12 miles from Ismay and about 30 miles from Terry. He built a comfortable log house of some six or seven rooms. It was pleasantly located on rising ground and commanded a wide view of hill, valley and plain – set off with the picturesque fringe of the celebrated Pine Hills. About the house were several tracts of cultivated ground and roomy stables, sheds and corrals. Just in the rear was a two-room “bunkhouse” – the usual adjunct of the Montana ranch home. One notable feature was the garden and orchard. Something over an acre in extent, the garden was one of the best ever seen and evidenced the care it had received. A thrifty young orchard was another feature unusual about ranch homes in this section.

In back of the house some distance was a big reservoir and, on the bank, or dam, a windmill and incomplete arrangements for irrigating a considerable portion of the valley immediately surround the house and grounds. Further down the valley were one or two large reservoirs and ditches for irrigating the land.

The house was painted white with a red metal roof, and the interior was provided with everything needful and comfortable. About on the hillsides and benches grazed the horses and cattle and near the barn big stacks of hay and grain showed the thrift and industry that built up a fine, prosperous ranch. Indeed, Oscar Brackett was a very successful Montana pioneer and buffalo hunter.

Notes:

1. Fort Keogh was established in August 1876, by Colonel (Bvt. Brigadier General) Nelson A. Miles for whom Miles City, Montana, is named. The original size of the Fort Keogh Military Reservation was 100 square miles, 64,000 acres. The original site, known as Cantonment on Tongue River, was abandoned in favor of a site a mile west of the original. The new site was officially named Fort Keogh, on November 8, 1878.

Source

The Story of Oscar Brackett, Pioneer, The Ismay, Ismay, Montana, November 18, 1908, Pages 1 & 8.