.35-40 Maynard 1882

A Minimum, but Effective Black Powder Silhouette Cartridge

feature By: Rick Moritz | March, 22

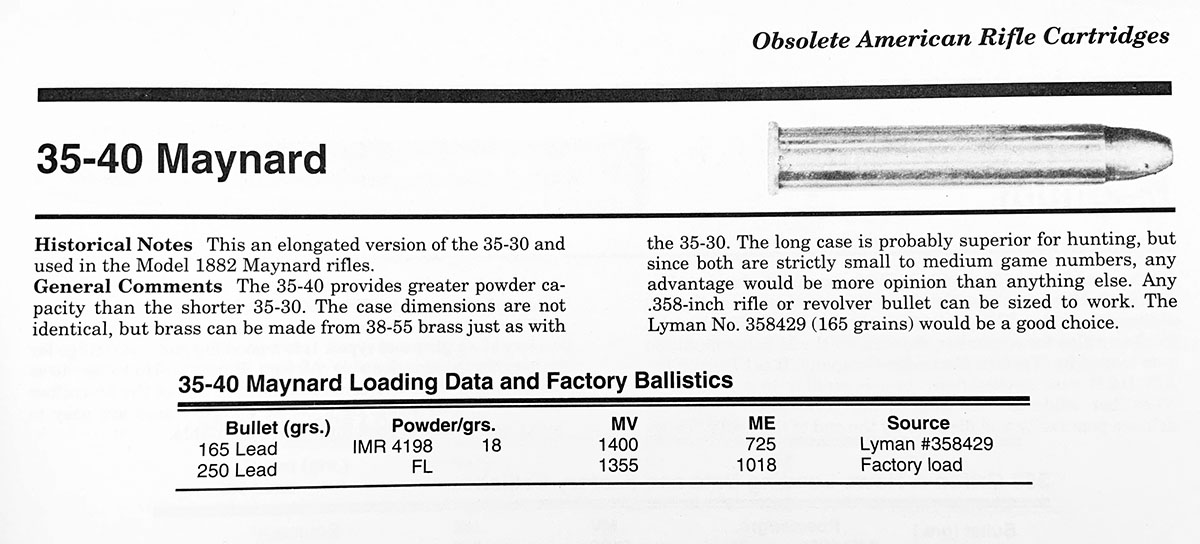

The Massachusetts Arms Company developed the .35-40 cartridge for its Maynard Model 1882 tip-up single shot, along with many other calibers. Before 1882, the Maynard cartridges had a very large diameter case head that was gripped by the fingertips for extraction. The 1882 series cartridges had what we would consider a normal-size case head.

The Maynard rifles were considered of excellent quality and were recognized as possessing great accuracy by the top shooters of the late 1800s. I have never had the opportunity to fire an original, but I have held a couple of very nice Maynard specimens. With minimal effort, the rifles seemed to hang on the target when held from the standing position. The balance and fit were recognized immediately. Unfortunately, the J. Stevens Arms & Tool Company purchased the Massachusetts Arms Company in the late 1890s and discontinued the Maynard rifle, not an uncommon way to eliminate the competition.

Cartridge Reloading

The case could also be easily fireformed from .30-30 brass, although they will be about .040 inch short. This would probably best be done using a small charge of pistol powder, Cream of Wheat cereal and a wax wad to retain the cereal. To allow chambering for fireforming the .30-30 case will require sizing in .35-40 dies to reduce the diameter at the shoulder.

I am careful not to overdo full-length sizing during reloading since this can cause “expander bulge.” The CH4D dies size the case slightly beyond what is necessary. Due to the over-reduced neck, the expander can leave a bulge in the case at the end of the expander travel. Adjusting the sizing die off of the shellholder and testing with the expander will determine how far the brass should be sized. I have found if the bulge is present, the cartridge runout will increase. After expanding with a .358-inch tapered expander the case will accept a .357-plus gauge pin.

Light sizing can create other issues that I have also found common to the .40-65 WCF and the .38-50 Remington Hepburn cartridges. The diameter, just in front of the rim, is not reduced during sizing and will tend to increase over time. After four or five firings, a shooter may find the cases want to stick during extraction. For the .35-40 Maynard, if the cases are full-length sized with a .38-55 WCF die, it will keep the base diameter at the appropriate size and eliminate the sticking problem. The .38-55 WCF die will only touch the bottom portion of the case and will not touch the neck area.

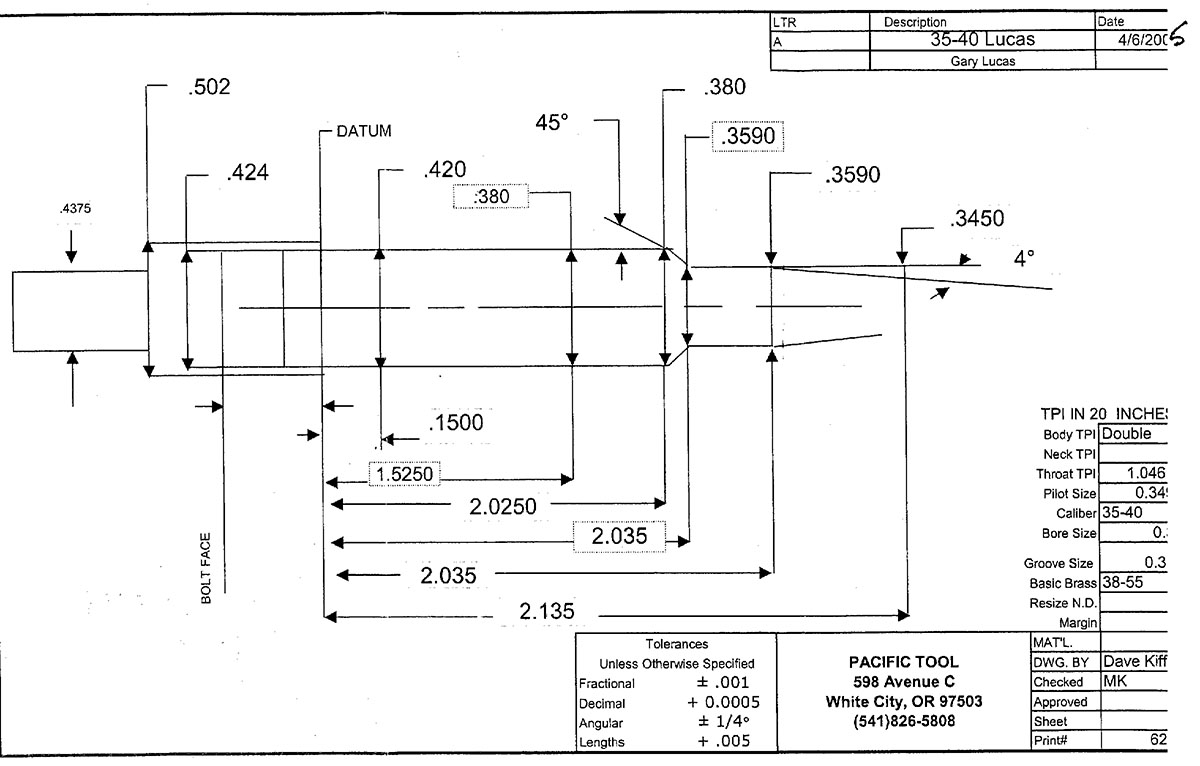

The .35-40 Lucas reamer is set up for .003-inch clearance on the .500-inch straight neck section so the brass does not require neck turning. After forming, using the .35-40 sizing die, the cases were 2.080 inches long and did not require trimming as this was the targeted brass length. Distance to the end of the chamber is 2.088 inches based upon the chamber reamer drawing.

I would like to share all the tests I have run with various bullet shapes, styles and weights. The truth is, I own one .35-caliber bullet mould made by Colorado gunsmith, Mike Lewis. The four-groove bullet weighs 340 grains when cast from 16:1 alloy. There are four bands behind the nose, diameters of the nose, and each of the four bands are in order .349, .351, .355 and .359 inches. This seems to mesh well with the four degrees per side of the chamber throat. This bullet has worked so well, I have not strayed. I know some .35-40 shooters that have tried a 200-grain cast roundnose pistol bullet for chickens. It is a relatively fast, low-recoil load. However, based upon shared information, the accuracy on paper at 200 yards was marginal.

The 340-grain bullet is 1.445 inches long, which would indicate a required twist of 13.4 inches (using the Greenhill Formula). In my opinion, there should be a margin of two inches between the calculated Greenhill twist and the actual barrel twist. The Douglas 10-twist barrel exceeds the minimum margin of two inches ensuring bullet stabilization to 500 meters. The bullet is seated .250 inches in the case, which helps preserve some of the limited case capacity. From the base of the bullet to the top of the second full-size baseband is also .250 inches. Based upon bullet runout measurements, keeping both the .359-inch bands within the case aids bullet alignment.

The bullet is firmly seated into the lands. Using mild thumb pressure, the cartridge stops .080 inch short of fully chambering. The Highwall action easily cams the tapered bullet into the rifling.

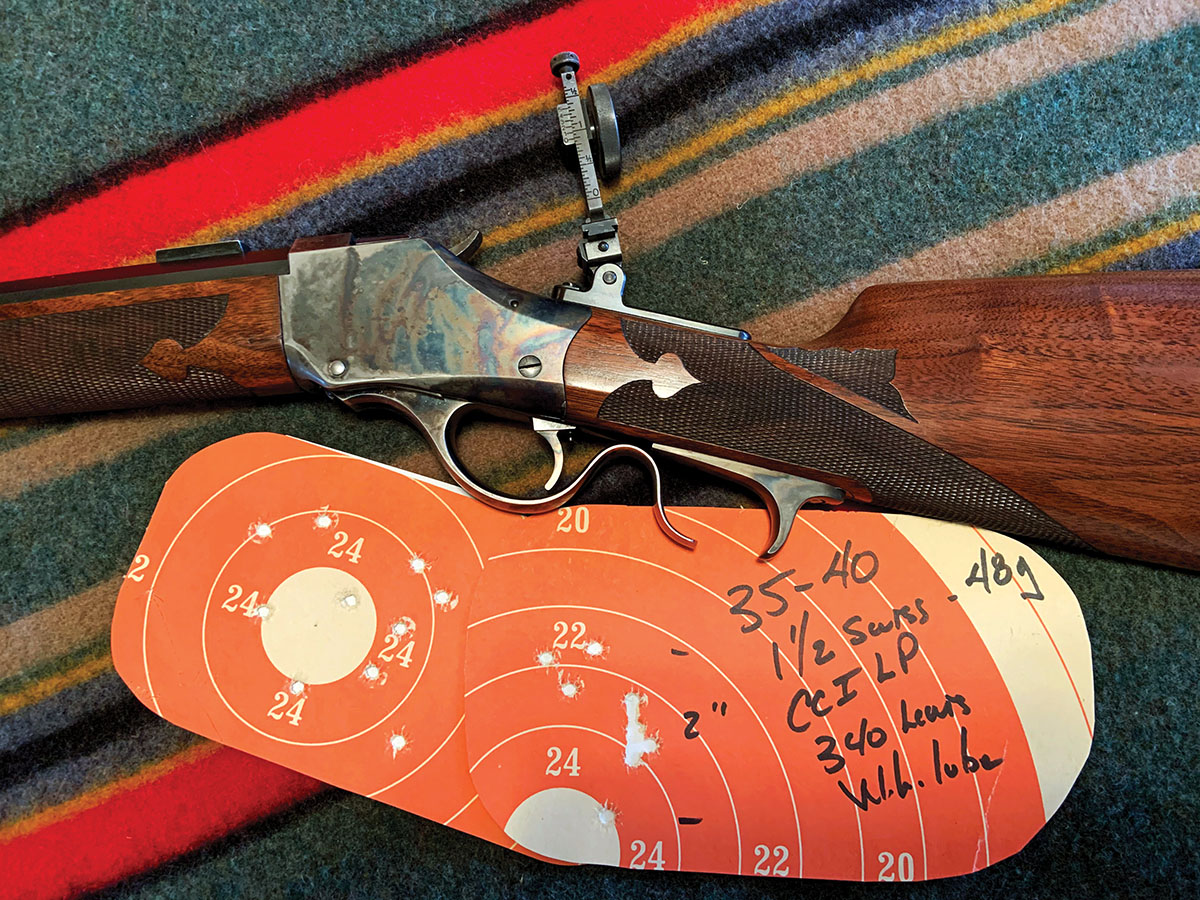

Typically, I have used 44 to 48 grains of black powder. One of the downsides of this cartridge is the limited capacity and small range of suitable charges. On the plus side, I have found that 45 to 48 grains are effective on rams and within that charge range, very accurate. I have always used CCI Large Pistol primers to ignite the charge. Typically, I would use the Federal Large Pistol primers, except I started with the CCI primers on a whim and have stayed with them. I have not noticed any increase in performance with 3Fg powder, although the fouling is harder. My preferred powder has been 2Fg Swiss, although 1½ Fg Swiss has shown to also work very well. I have a new case of 2Fg Swiss powder and I completed some confirmatory load testing, which is discussed further.

Gary Lucas and I crossed paths at the Colorado and New Mexico BPCR Silhouette matches. We also corresponded by regular mail as well as email. When encouraging me to try the .35-40 Maynard, he mailed me a dummy cartridge, chamber drawing, and details on his loading. Regularly, he would email me the latest monthly silhouette results from Kansas.

The details for the Gary Lucas .35-40 load are as follows: 1.445 inches long with a 340-grain, Brooks grooveless bullet. Since the bullets had no grease grooves, they were dip lubed and slip-fitted into the unsized case. The bullet nose was .349 inches in diameter with a .400 long cylindrical section of .358 inches. Gary’s standard load was a powder charge of 46 grains of 2Fg Swiss with .100 compression and a .090 poly wad. The bullet was .300 inch in the case, with a reported velocity of 1,200 feet per second (fps). Gary was also using a Douglas 10:1 twist barrel. Between shots, the barrel was cleaned with Bore Weasels. Bore Weasels are a small-brush apparatus, usually with an O-ring or felt wipers that are kept in a cleaning solution and pushed down the bore between shots. Behind the Weasel is normally a dry or slightly wet cotton patch.

Gary always did well in windy Kansas with his .35-40. Sometimes the wind blows so hard the targets are clamped to the stands. When the clamp won’t hold, they end up shooting on swingers. The .35-40 was competitive in the prevailing conditions.

The Rifle

Mike Lewis fitted and chambered the #4 octagon Douglas 10:1 twist barrel, .350 inch by .358 inch, bore and groove. The .35-40 Lucas Pacific Reamer was used. Originally, the barrel was 32 inches, but was very difficult to shoot offhand and did not hang well. I subsequently had it reduced to 29 inches.

With irons, the rifle comes in at 12 pounds, 2 ounces; and 13 pounds, 5 ounces with an MVA scope. The barrel has been drilled and tapped for 7½-inch Unertl spacing, as well as 17-inch spacing for an MVA scope. The listed weights include a mercury recoil reducer in the buttstock. Certainly, the recoil reducer increased the shooting comfort but was added to enhance the offhand balance of the rifle. Anything worth doing is worth overdoing, so the rifle also has a Pachmayr decelerator recoil pad. This setup has resulted in the most comfortable BPC rifle I have ever fired.

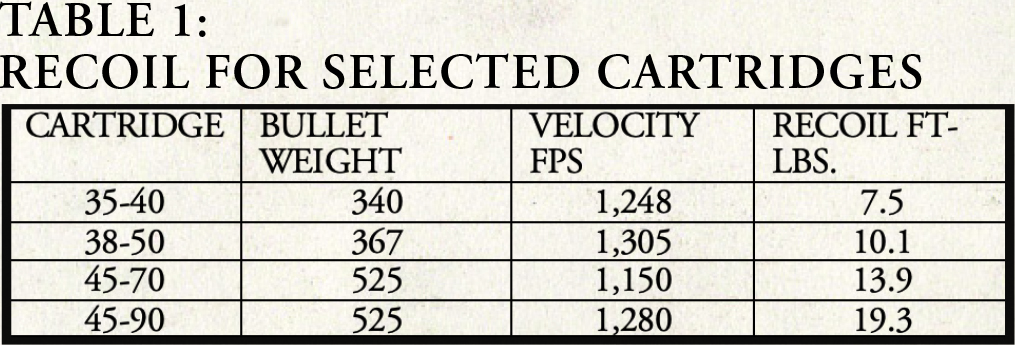

Presented in Table 1 are the relative recoil numbers for various cartridges assuming that each rifle weighs 12 pounds. The .35-40 is very mild-mannered by comparison and yet, is still fully capable of competing in BPCR silhouette.

Load Development

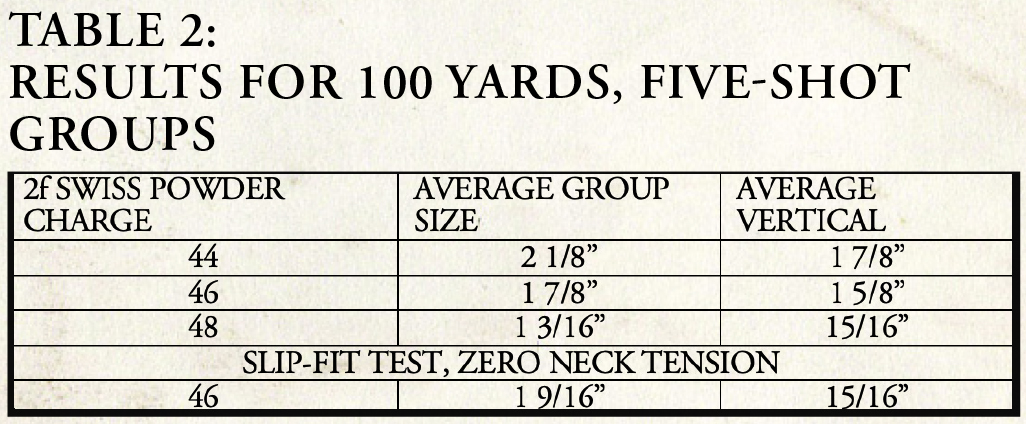

Normally, I would complete the load development at 200 yards, but access to my local 200-yard range was not available due to storm damage and drainage issues. I used the 100-yard range and planned to do some confirmatory testing at the 200-yard range when available. Typically, I use .001 inch to .002 inch neck tension, but I tried some slip-fit as well as some different wads; fiber, beeswax sheet and poly. As mentioned, the .35-40 Maynard has a very limited range of effective powder capacity. Charges of 44, 46 and 48 grains of 2F Swiss lot 14/03/2017 were tested. This was based upon prior work with this rifle.

I put a .050 beeswax wad on top of the powder followed by either a fiber or poly wad. Intuition tells me the addition of the wax wad would create a super seal and result in better accuracy. Well, my intuition was not very good. Having tried this configuration in the past, I did not experience any magical improvement. I have had better results by using multiple fiber, felt, and poly wads. The wax wads were not a total bust but they did not improve group size. My wads are pure beeswax and a bit rigid. My understanding is they will reduce leading so if a shooter has that issue, you might give them a try. All tests reported in Table 2 are using .090-inch poly wads and three, five-shot groups.

I have completed extensive slip-fit testing with my other rifles and have had indifferent results. The slip-fit test for the .35-40 Maynard showed some very promising results, which will be retested in the future. I was convinced I was the only BPCR shooter that could not have acceptable results with zero neck tension; so, at last, a bit of success.

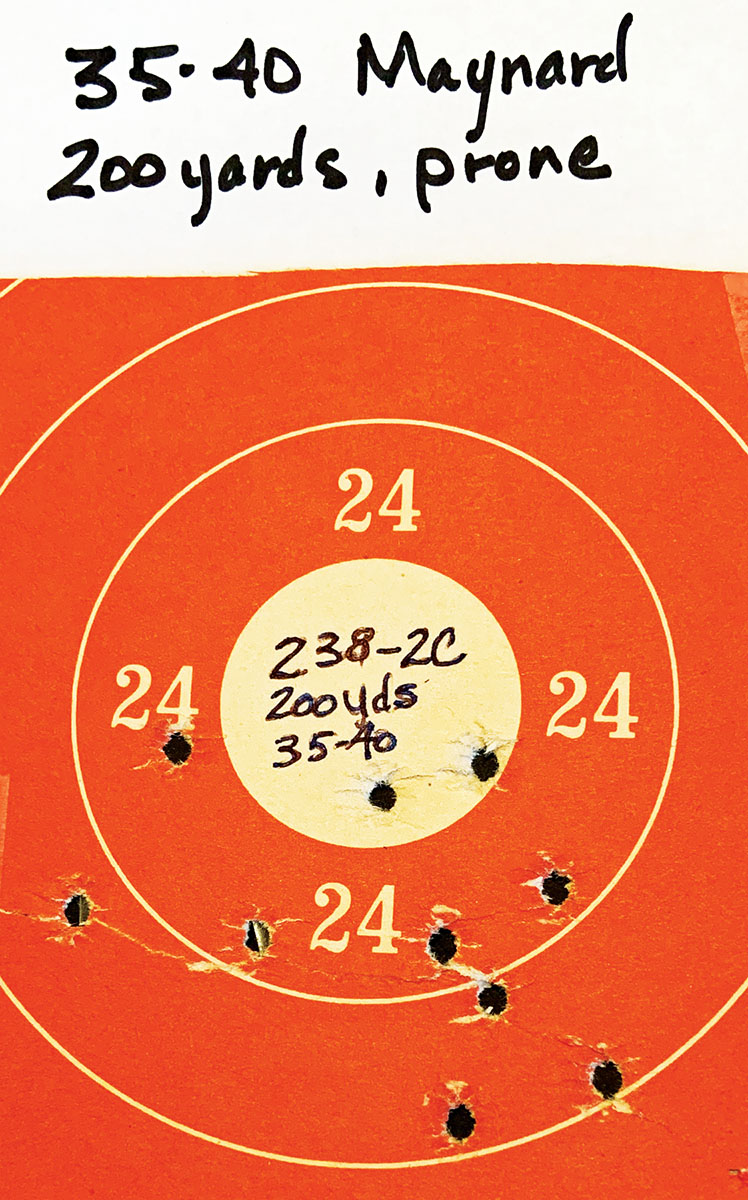

Based upon the results from the 48-grain 2Fg testing an additional confirmation 10-shot group was fired at 200 yards, group size 25⁄8 inch, vertical 1¾ inch. The 340-grain Lewis bullet was 16:1 and seated to an overall length of 3.285 inches, which resulted in .155 inch of compression. Again, neck tension was .002 inch using a .090 poly wad and CCI large pistol primer. The 200-yard group was not surprising as this rifle had performed well with the same charge using a different lot of powder. It was reasonably well centered and would have scored 238-2C in a Schuetzen match; a decent score for black powder.

Fouling control for all groups was two arsenal patches mildly saturated with 10 percent NAPA soluble oil in water. Each patch was pushed from breech to muzzle with a nylon brush and allowed to fall on the ground at the muzzle. I have not attempted blow tubing with this cartridge.

Performance

The .35-40 Maynard has demonstrated the ability to shoot BPCR silhouette Master scores. In my first silhouette match with the rifle, I was able to post a 34/40 score. Later, I was able to set the range record at Rifle, Colorado, a score of 35 in a 40-shot match. I do not know if the record still stands. The rifle was set aside for match shooting while I sorted through the excessive annealing issue and the associated high shot, low shot dilemma. Simple problem, but it took an effort to sort out.

The .35-40 Maynard does have limitations. This is not a rifle one would take to a gong shoot; the bullet impacts can be difficult to see if the gongs are shot up, and if a shooter happens to get off the target, the .35 will not kick up a lot of dust as a .45-caliber bullet will. If you have ever been in a gong shoot and got off target with no visible impacts, you know exactly what I am talking about.

Being extremely biased to the .38-50 Remington Hepburn, I would still state that the .35-40 Maynard is a very good silhouette cartridge. Although I have great difficulty setting the .38-50 aside long enough to work with something new, I do think the .35-40 is very competitive. Considering the lack of recoil and ease of load development, it has an advantage over many other cartridges. At the end of the day, the best cartridge for a shooter is the cartridge and rifle they believe in.

Having campaigned the .38-55 WCF cartridge in multiple rifles, I feel it has marginal case capacity to push a 360- or 370-grain bullet to adequate velocity. The case is better suited to a 340-grain bullet or a bit less. In my opinion, the .38-55 case capacity is better suited to a .35 than a .38 caliber bullet.

A 340-grain bullet out of a .38-55 is a stubby bullet, while a 340-grain, 35 caliber is a long, sleek, wind-defeating projectile. It is so thin and slippery that the “devil wind” has great difficulty finding the bullet.

Gunsmiths

I know of two gunsmiths that have reamers for creating .35-40 Maynard rifles. Steve Baldwin: Steve shoots the .35-40 as his primary midrange BPC rifle. Steve does wonderful work and knows how to make the cartridge work. Contact information: Mechanical Accuracy, Jones, Oklahoma, baldwinsights.com, 405-399-2875. The other is Mike Lewis: Mike is the gentleman that chambered and fit the .35-40 barrel to my Highwall and also made my .35-caliber bullet mould, but I am unsure if he still makes moulds. Contact information: Colorado Gunsmith, remhep3@gmail.com.