The Wyoming Schuetzen Union’s “Center Shot”

The Kephart Bullets

column By: Jim Foral | August, 21

The name of Horace Kephart was a familiar one to readers of Forest and Stream magazine. His letters postmarked St. Louis, Missouri, were not like the insipid prose of the mainstream that were allowed to see print. Kephart was a polished communicator who held his pen until he was able to make an actual contribution. He had qualified himself as an authority on camping and woodcraft. This included eating his own cooking done over an open fire. He was well versed in western history and often lectured on the topic.

Horace Sowers Kephart was born in Pennsylvania in September 1862, but grew up in Iowa. He studied at Boston University, spending much of his time haunting the library stacks, and it was there that he developed an interest in librarianship. In 1880, he studied political science and history at a postgraduate level at Cornell, and worked his way to graduation in the school library. He took a bride, Laura, in 1887, and then accepted a job at the library of Yale University. Three years later, they moved to St. Louis where he directed the St. Louis Mercantile Library, and spent as much time as possible on the banks and backwaters of the Missouri River, camping for days at a time.

When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, Kephart began to recruit a company of volunteer riflemen to strike out for Cuba on their own. Charles Askins Sr., the grand old shotgun authority, volunteered his services as a rifle instructor. The short eight-month duration of the war caused Kephart’s project, and others like it, to be abandoned.

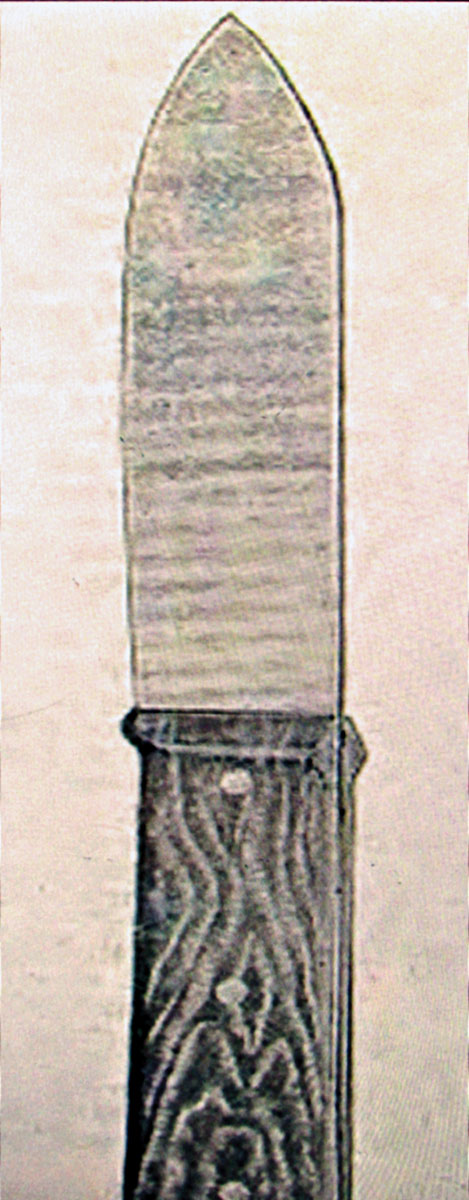

When an 1899 discussion in Forest and Stream centered on practical knife designs, Kephart submitted a drawing of his knife, which Emerson Hough, staff conductor of the discussion, considered to be “my idea of a good meat knife ‘round camp. Just a plain business knife made of steel that will take and keep an edge.” Kephart’s was a practical woodsman’s knife drawn up by a practical woodsman. The cut submitted in the April 29, 1899, shows a rough, somewhat oversized handle that was a crude slab of wood secured with rivets. The edges of the 5-inch blade were parallel until they abruptly right-angled to a point. Kephart’s plainer-than-plain looking knife was a tool only. Readers remarked kindly on its utter simplicity and utility. A very few Kephart knives were made by Colesser Brothers in El Dorado, PA. Copies for collectors have been replicated in recent times.

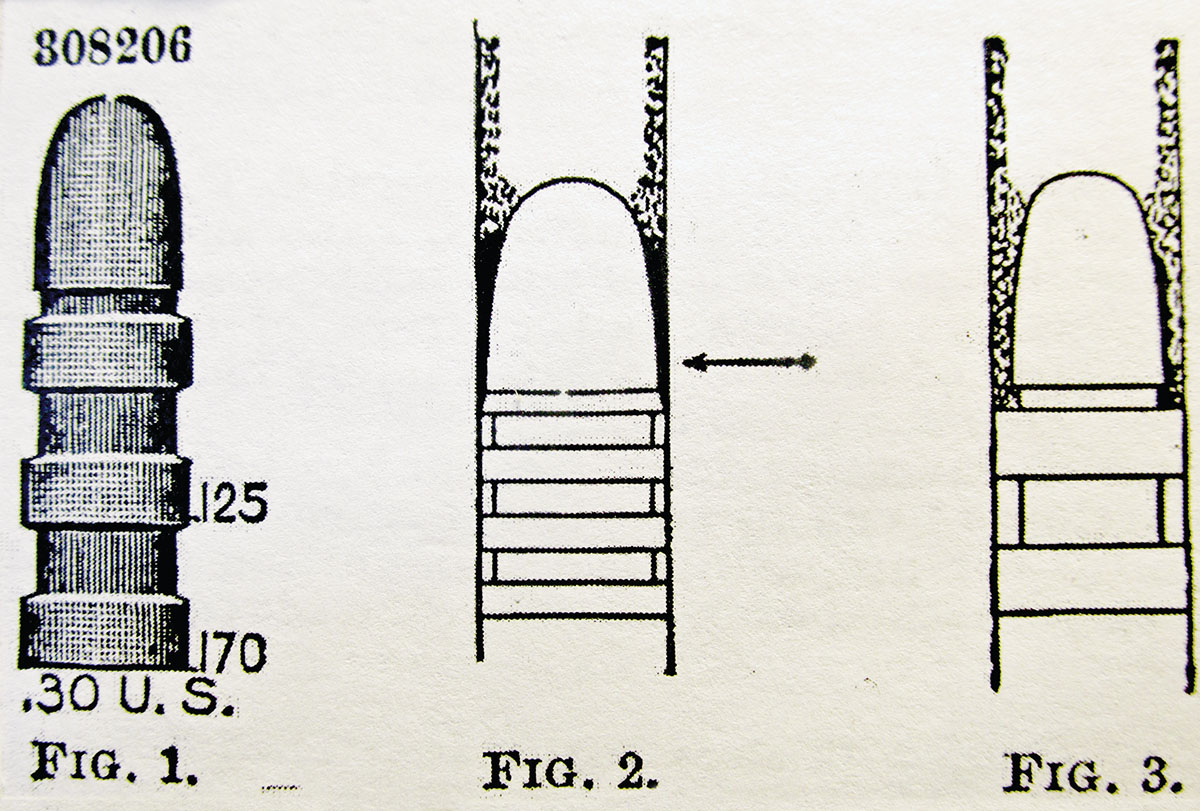

The Kephart design didn’t have the familiar look of the Ideal pattern. Kephart’s was a fresh and unorthodox design that suggested his profile had been carefully reasoned out and followed no formula. By 1900 standards, Kephart’s 308206 bullet may have gone dimensionally overboard. At the largest diameter of its radically squat nose, the .30 caliber version mics .28 inch, providing a .010-inch clearance between each land, in a somewhat misguided exchange of the outmoded dirt-scraping band for the meaningful guidance of a more closely fit nose. The spacious vacancy resulting served as a reservoir for whatever “dirt” and smokeless powder residue that might have accumulated, which was then theoretically carried out the muzzle.

John Barlow himself defended this feature and vaunted it as his company’s pioneering effort. Ideal had originated the concept of forward scraping bands during the black powder days when it may have been a beneficial feature. Over the years, the scraping band had been offered in moulds cherried in several weights and calibers. The base of Kephart’s “nose” was undercut a bit to hold lubricant with the intent that the first part of the bullet’s contact with the bore was an anointing of lube. Kephart made his bands broad and stout to withstand the wrench of the Krag’s quick 10-inch rifling pitch. The grooves may have been made inordinately deep, but they held a lot of lubricant.

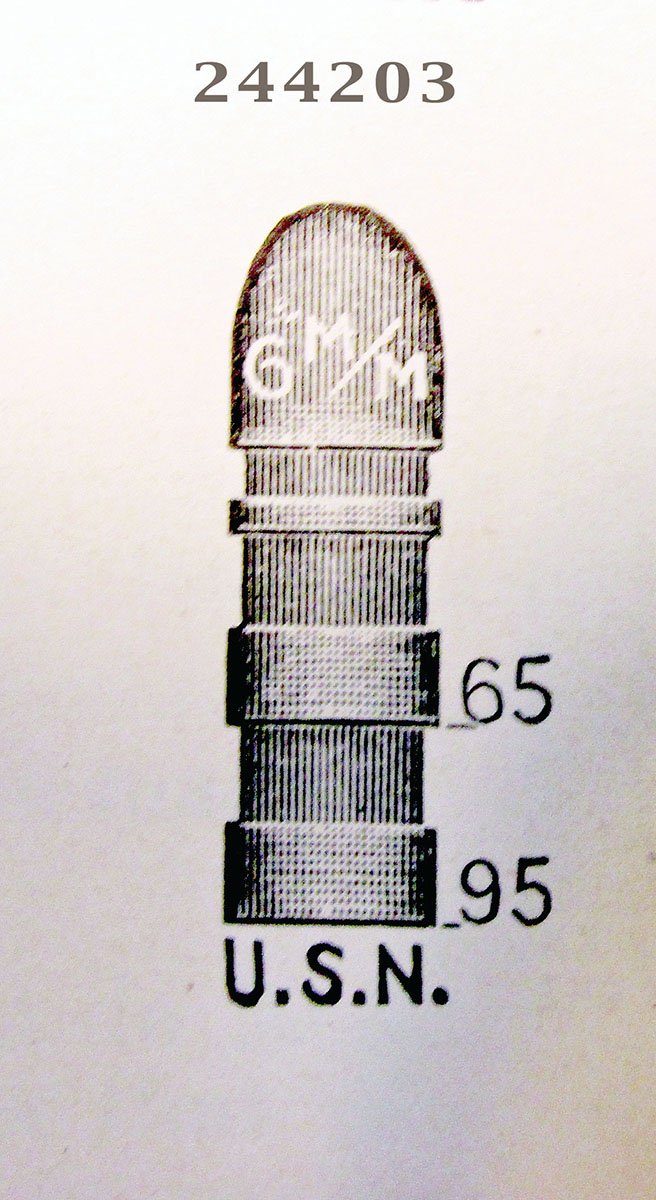

Barlow cataloged five different Kephart bullets in his Ideal Handbooks. Each was designed for the smokeless powders of the day, and the cartridges intended to handle them. The readily recognizable Kephart form was retained and the bullet weights varied proportionately to the scaled up or down version. Adapted to the 6mm USN cartridge for the Winchester Model 1895 Lee, there was a 65-grain short-range bullet and its longer 95-grain counterpart with three bands, both answering to 244203. The U.S. Navy ordered an ample supply of Ideal mould for use by its troops.

With a .25 caliber bullet neglected in the Kephart lineup, Ideal provided one along the same lines, including the wide base band, and the lube ring ahead of the front band. Noticeably a departure from the Kephart style was the absence of the broad dirt-scraping band. Ideal number 257231, introduced in 1902, could be had in 66-, 88-, and 111-grain weights.

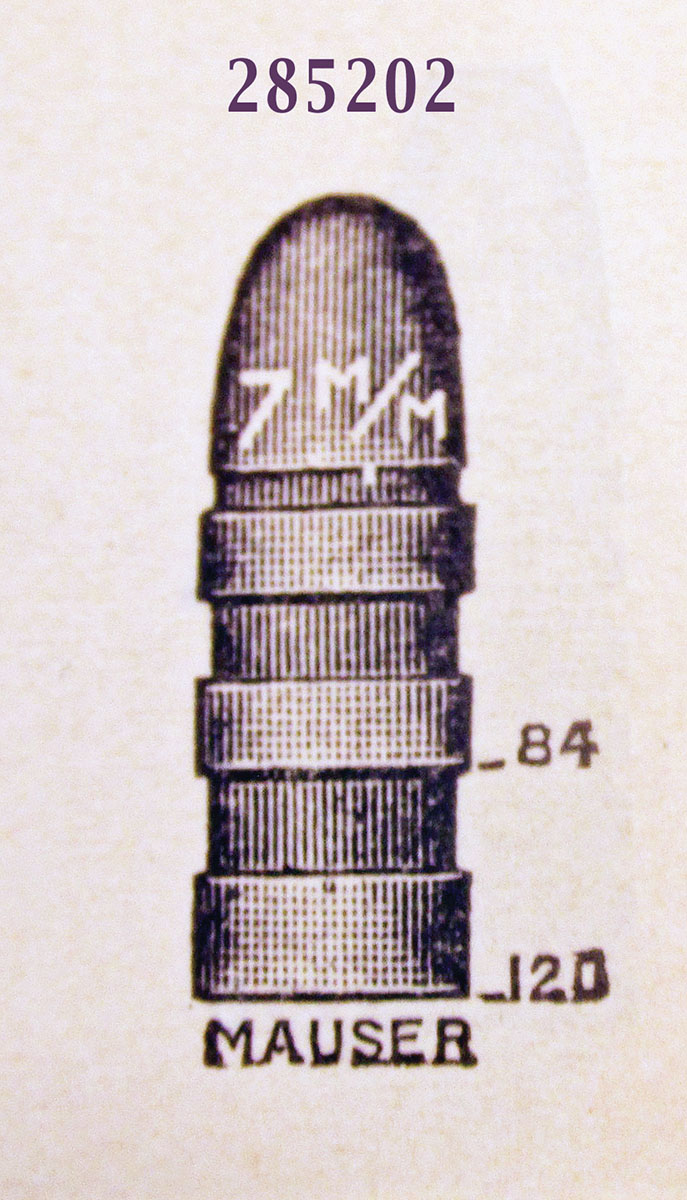

Assigned number 285202 was the Spanish Mauser’s 7mm bullet, which came in 84- and 120-grain weights. The .30 caliber Kephart bullet for the Krag and .30 W.C.F was 308206 in both 125- and 170-grain styles. Barlow provided 311207 for the .303 British shell. 317204 fit both the 8mm “J” bore used in the various imported Mannlicher types, as well as the domestic smokeless .32-40 rifles.

The .30 caliber Kephart bullets got the big push and the most use of the entire series, while the others didn’t get much attention. There was one magazine account of the 285202 on the range in a Mauser rifle. The bullets all landed in a 4-inch circle at a hundred yards and a cut of the target was provided as proof. Ned Roberts, identified by his “N.H.R.” signature and distinctive style, wrote from Gloversville, New York, in 1905, about the good shooting he was able to do with his .32 Special Remington Lee sporting rifle sighted with a Mogg six-power telescope. Roberts was using the 317204 180-grain bullet cast from the early rock-hard Hudson smokeless lead alloy (80-10-10) lubed with Kephart lubricant. Roberts was able to shoot particularly close 200-yard groups with the rig.

Kephart was believed to have marketed his bullet lubricant but in 1900, divulged this simple recipe for the common good: “Melt over a slow fire three parts of crude ozocerite and two parts Vaseline.”

If the notices in the sporting magazines are an accurate indicator, the 125-grain version of Kephart’s .30 caliber may have outsold the longer 170 grain. There are many examples of the 125-grain bullets trials at the 200-yard mark, but very few printed about the heavyweight. One such is an account of a 200-yard target shot with a Krag. Ten 125-grain shots each landed on a 4-inch target paster. This may have been exceptional enough to merit publication, but it did happen and demonstrated the possibility, if not the likelihood, that these groups could happen to someone else. Dr. Walter Hudson’s experiences, which were really the ones that mattered, were along these same lines. In his 1903 book, Modern Rifle Shooting from The American Standpoint, Hudson stated that “good results” can be obtained up to 200 yards with the 125-grain Kephart bullet.

By mid-1902, America’s short-range shooters were using the new Kephart bullets almost exclusively. This wasn’t the first craze to smite them. Many were reporting results with handloaded Kephart bullets better than they had seen with factory or government cartridges. Curiously, that year Kephart set aside his own .30-caliber bullet, and in a letter to Hudson, admitted to using instead a load worked up by Professor J.A. Grening of Scranton, Pennsylvania. In essentials, it constituted a “160-grain .30-30 bullet” (no Ideal number fits, but the Winchester 160-grain full patch, flatnose bullet does) that was actually .003 inch sub-caliber, and brought to .308 inch in a special swage. The powder charge was 14 grains of Laflin and Rand’s Sporting Rifle Smokeless. Kephart’s .30-40 Winchester Single Shot (he also used a Remington-Lee .30-40) would group this combination reliably into 6 inches at 200 yards. Hudson and Kephart had dabbled with both black and semi-smokeless powders in the low velocity target loads, with each reporting poor results.

The practice necessary to become proficient at the trendy pastime of military rifle shooting was dependent upon a steady, plentiful supply of Krag ammunition, which was doled out very miserly by the military powers to the eastern National Guard units. Hudson saw low-cost cast bullets as the probable solution to the acute practice ammunition problem. First, a .30-caliber bullet had to be selected and accurate loads worked up to 500 and 600 yards. This was totally uncharted territory, and one that posed a challenge that cried out for a knowledgeable and resourceful individual capable and willing to devote himself to the task. Hudson took on the project with the same zeal and level of self-application that he had become well-known for.

His first trials used the Ideal .30-caliber bullets available in early 1903. These included W.H. Cooper’s 3081 – 200, familiarly known as the Cooper bullet, and the heavier of the Kephart bullets because it fit the same criteria as the Cooper. Whatever hope Hudson may have had for the 170-grain Kephart bullet was rejected very quickly owing its lack of proper weight and length to meet his long-range performance goals. The Cooper bullet was also rejected for failure to group. Results with both bullets at 600 yards were pretty grim.

Hudson’s progress advanced by degrees, with each new bullet design incorporating lessons learned from previous failures, and embodying the positive features. Indications gathered from examining recovered bullets showed that failure to achieve the necessary accuracy was the loose bore fit of the early bullets. Undersized noses did little to align the bore with the projectile was something else learned from trial and error. Bullet shanks were enlarged to bore diameter to better guide the bullet to the target. Hudson and Barlow put their heads together and fire walled the bullet base with a thin cup of copper in what became the project’s culmination, the Ideal 308284, which adopted the Kephart-influenced, lube-holding undercut at the base of the bullet nose.

By 1905, Hudson’s progress had reached a point where he considered the project completed. “Improvements in that direction have followed one another, it is hard to keep pace with them,” he wrote. He had analyzed all the data, gathered the opinions of his associates in the project and standardized his recommendations for bullets and loads for each range. For short-range indoor gallery rapid-fire practice up to 40 yards, the National Guardsman needed a bullet that would feed positively through the Krag magazine, a shortcoming for the short-nosed 125-grain Kephart. For slow fire, it was fine, and 6 to 8 grains of Marksman made a good gallery load.

For ranges up to 200 yards, where the Kephart 170 grain had once shined, Hudson recommended the plain-based 308278, 308274 and 308280 with 15 grains of Marksman. Hudson’s bore-corking 308259 with its .315-inch forward band was in use by some, though it had been quickly superseded. Ideal number 308284, which John Barlow did a masterful job of promoting, with an almost universally used charge of 23 grains of Lightning (1,550 fps) ruled the roost at National Guard competitions and practice until the Springfield rifle was fully adopted. With the Springfield came a new outlook; practice and training cartridges were dispensed much more generously.

New .30 caliber bullets from Ideal hopelessly outclassed the Kephart designs. 308241 and 308291 took the place of 308206 - 125 grain, and most of the bullets that came out of Hudson’s trials outperformed the Kephart 170 grain.

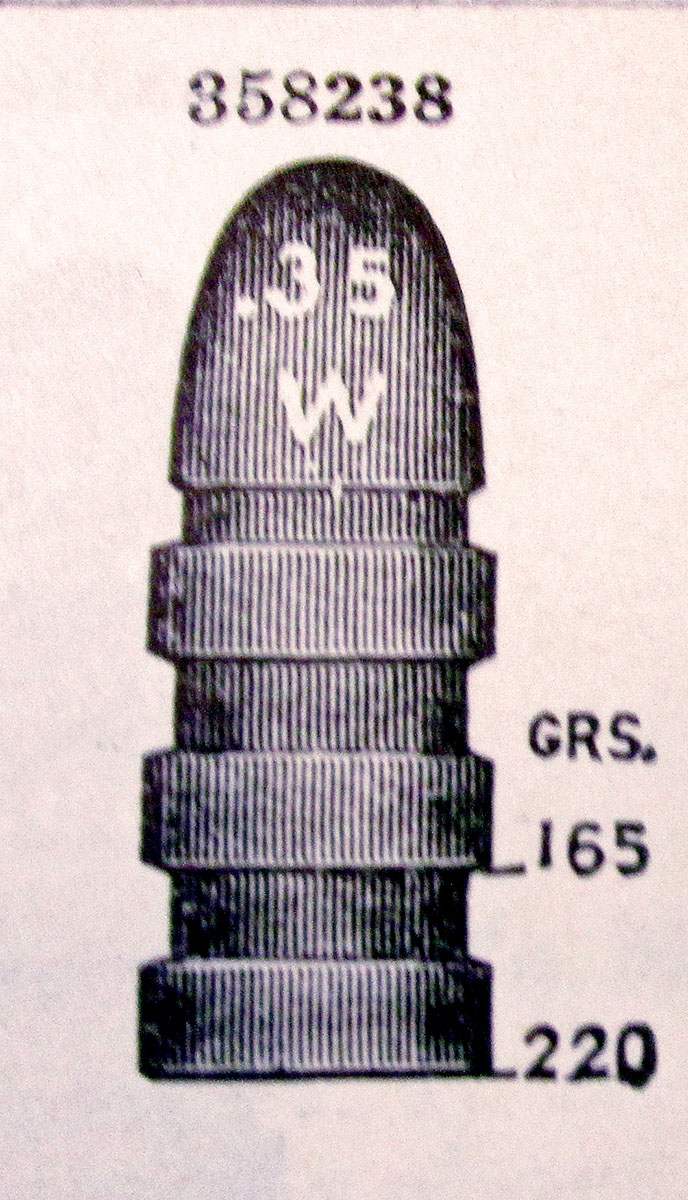

John Barlow had such faith and confidence in Kephart’s basic bullet form that he admitted its influence in Ideal’s design for the new .35 and .33 Winchester cartridges. When Ideal 358238 was unleashed in 1903, it was a ringer for the Kephart in silhouette but scaled up to .35 caliber. Like the Kephart, it could be had in a short-range version that weighed 165 grains while the full-length, three-banded version weighed 220 grains. The Ideal 336237, the .33 W.C.F. bullet, was pure “Kephart” except for its flat nose.

In 1904, Horace Kephart moved to North Carolina after a serious bout of poor health. It was there that he continued to pursue his interest in writing. During that same year, he put his considerable knowledge on display when he wrote a chapter on hunting guns for Guns, Ammunition, And Tackle, a wide-selling book for the day. After a solicited eight-part series for Outing on basic rifle marksmanship and gun selection, and his other fortes of camping and woodcraft, he continued to contribute to that magazine.

Over the years, Kephart educated himself about the field of ballistics and discovered that he had a head for it. He grew in understanding of ballistic shapes and profiles to the point that he was an authority on the subject. He was the gun editor of Outing magazine, a very popular monthly magazine about recreational pursuits and was touted by Outing Editor Albert Brill, as “one of the three or four men in this country qualified to speak with authority about guns and ammunition.” Kephart also conducted the magazine’s monthly Question and Answer column. Kephart was not content with theory, but put theory to the test and into practice. Unable to find someone to make a mould for a double-pointed bullet, he hired a mechanic to lathe-turn a supply of .45 caliber lead bullets with a heavy hemi-spherical base. He shot them backwards in a Springfield .45-70 and learned that they would shoot point on in his rifle.

Kephart wrote about bullets with mastery and understanding. You can take my word for it, or locate a copy of Outing for October of 1919, and read “The Best Form of Bullet” and see for yourself. Be prepared to be dazzled by the man’s acumen on the subject.

His bibliography is as impressively diverse as it was extensive. His byline was among the favorites in all of the outdoor sports periodicals over the years. He was the longtime Arms and Ammunition column editor for Outing and All Outdoor magazines. He was an effective advocate for conservation and was instrumental in the institution of the Appalachian Trail and a principal motivator for the creation of the Great Smokey Mountain National Park.

Horace Kephart died in an automobile accident near his home in Bryson City, North Carolina, in January 1931. The AMERICAN RIFLEMAN remembered him as “one of the pioneers of the then new smokeless powders and lead bullets for use in high power rifles.”