The .38 Long Colt

Weakling Cartridge or Mismatched Gun and Ammunition?

feature By: William M. Curry, Jr. | June, 22

Antecedents

Colt firearms developed the .36 caliber percussion revolver as a lighter intermediate revolver between the much larger .44 Dragoons and the much smaller .31 Pocket models. Colt introduced the .36 Navy, or Belt model, in 1850, which became known as the Model of 1851. This revolver set the standard for a revolver of medium size, reasonable power and modest recoil that could be carried comfortably in or on the belt of one’s person, rather than in saddle holsters or a pocket. Butler (1971) cited the 1861 Ordnance manual showing the .36-caliber percussion revolver paper cartridge as having a 145-grain, ogival bullet with 17 grains of black powder for a muzzle velocity of approximately 745 feet per second (fps)1. Most .36 percussion revolver barrels had a bore or land diameter of around .360, a groove diameter of .370/.375 and used a roundball or conical bullet .375/.380 in diameter2.

The .38 Long Rimfire cartridge was introduced in 1860 for use in the Bacon revolver and the .38 Short Rimfire, and in 1861 for use in the Prescott Navy revolver3. The .38 Long was typically loaded with a bullet of around 150 grains and an 18- to 21-grain black-powder propellant charge, which produced approximately 750 fps muzzle velocity. The .38 Short had a 125- or 130-grain bullet and 15 to 18 grains of black powder. In both cases, outside lubricated, heeled lead bullets were used of .375 to .378 diameter4.

The .38 Long Rimfire cartridge was extensively used in factory or other conversions of .36-caliber percussion revolvers. Large quantities of Colt and Remington conversions were sold. Remington cataloged these rimfire conversions at least until 1889.5

The first .38 centerfire handgun cartridge introduced was the British .380 Revolver cartridge around 1865. This cartridge was first produced in the U.S. around 1870, as the .38 Webley. This cartridge had a .375/.380 diameter, an outside lubricated, heeled bullet of around 124 or 125 grains with a black-powder charge of 16 grains6. Hatcher (1935) stated that the powder charge was 10 grains7. ICI was loading this cartridge with 10 grains of black powder as late as 19558. This cartridge is generally regarded as interchangeable with the .38 Short Colt9.

The U.S. Army had begun procuring metallic-cartridge revolvers, primarily Remington New Model Army conversions in .46 rimfire before June 186810. The army acquired other cartridge revolvers between 1869 to 1872, notably the Smith & Wesson American revolver in .44 centerfire and the Colt Richards conversion of the 1860 army revolver in .44 centerfire. The army adopted the .45 caliber Colt Model of 1873, in July 1873. Most of the regular army was reequipped with this revolver in 1874 and 187511.

In contrast, in 1873, the U.S. Navy was still using Colt and Remington .36 percussion revolvers procured during the Civil War. That year, the U.S. Navy expressed an interest in converting the Colt .36 Navy revolvers to use a centerfire cartridge12. The U.S. military preferred centerfire cartridges because a rimfire case was weak and the priming was not always distributed equally inside rim, resulting in misfires13. The navy also decided to convert Remington percussion revolvers in 187514.

The Cartridge, The Army Revolvers and Use in Combat

The .38 Short and Long Colt cartridges became available in 187415. The .38 Long Colt as introduced, had an outside lubricated, heeled bullet of .375 to .379 diameter of around 130 to 150 grains. The powder charge was 18 to 21 grains of black powder. The case had a length of .85 to .88 inch. This cartridge was used in centerfire conversions of Remington and Colt .36 percussion revolvers. The U.S. Navy sent quantities of percussion revolvers that they had in inventory back to the Remington and Colt factories to be converted to use this cartridge.16

Colt also used this cartridge in its 1877 Lightning double-action revolver.17 This version of the .38 Long Colt with the .88-inch case and the outside lubricated bullet is often referred to as the .38 Colt Navy18 or as the “Caliber .38 Ball, U.S. Navy.”19 The various versions of the .38 Long Colt were also sometimes referred to as the .38 D.A. or the .38 Colt D.A.20 as it was commonly used in double-action revolvers. Some Colt double-action revolvers were just marked “Colt D.A. 38 inch on the barrel.”21 The .38 Long Rimfire and the .38 Colt Navy were essentially the conical bullet and powder charge of the .36 percussion revolver wrapped in a rimfire or centerfire case.

In 1889, the navy decided to adopt a modern revolver, the Colt Model of 1889 New Navy Double Action.22 This revolver used the .38 Colt Navy version of the .38 Long Colt. In 1892, the army decided to adopt the Colt double-action, side-swing cylinder revolver in .38 caliber. The first such was the New Army Double Action Model of 1894.23 In 1892, Frankford Arsenal started experimenting with production of a .38-caliber revolver cartridge based on blueprints of the Union Metallic Cartridge version supplied by the Colt factory.24 These drawings called for a powder charge of 18 grains.

The army believed this charge was excessive and reduced it to 15.4 grains, which produced a muzzle velocity of 750 fps.25 It had an inside lubricated bullet of around 148 grains with a diameter of .353.26 This cartridge was referred to as the “Caliber .38 Ball, U.S. Army,”27 or as the “.38 Colt Army.”28

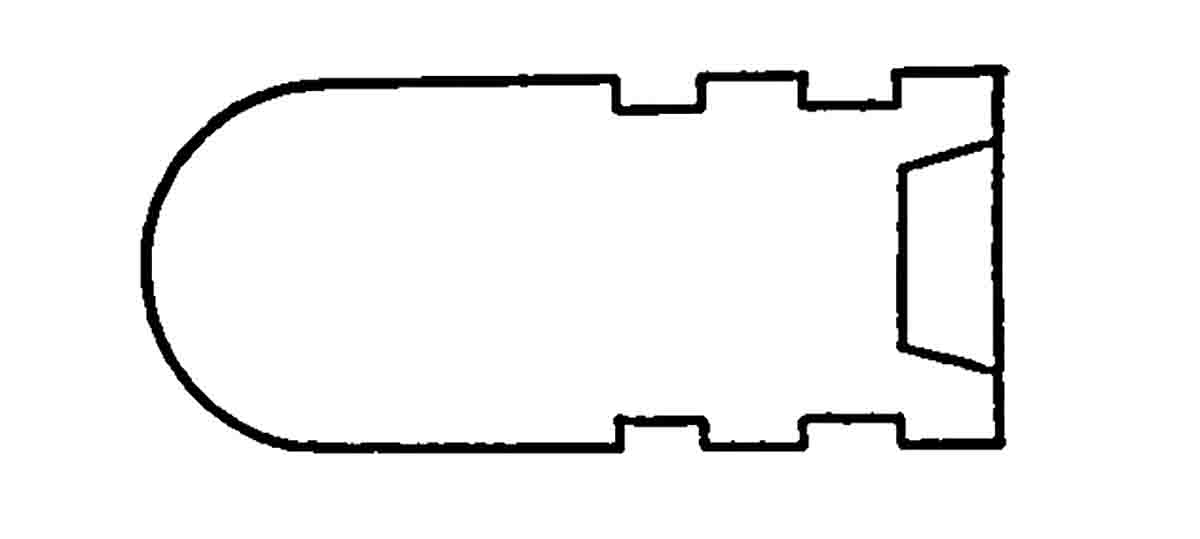

The bullet had a diameter of .353 inch and was described as a “recessed base.”29 (See figure 1.) This is not a deep hollowbase as found in modern hollowbase wadcutters, but a shallow dished in base.30

This bullet was used from 1892 until 1909. It was replaced with a bullet with a deep true hollowbase in 1909, “which was designed to produce a better gas seal when fired.”31 Appendix 13 of the Report of the Chief of Ordnance (1893) gave the bullet weight as 150 grains, the diameter as .357 inch and the propellant charge as 16 grains of “small arms powder.”32 Ordnance Pamphlet No. 1919, (1917) lists the bullet weight as 148 grains and the bullet diameter as .357 inch and the powder charge as 3.5 grains of “a nitroglycerin sporting powder similar to that used in shotguns.” It also stated that the exact charge varied by lot and type of powder.33

Himmelwright (1908) stated that most revolver bullets were undersized and designed to bump-up when fired by black powder. He further stated that reduced black powder or full charges of smokeless seldom would cause the undersized bullet to bump-up to fill the grooves. A lot of revolver bullets had concave bases to facilitate this process. When used with smokeless or reduced charges of black, the hollowbase must be larger or the bullet will suffer “gas cutting” and inferior accuracy.34

The last production of military .38 Long Colt ammunition occurred during World War I, when the older .38 revolvers in inventory were put back in service for the Navy and troops in the U.S. and rear areas overseas. This production was by Remington and utilized a 148-grain hollowbased bullet with 3 grains of Bullseye powder. This was Remington’s commercial load with minor modifications.35 Remington continued to load this cartridge commercially until the 1970s. The Index # R38LC was last listed in the 1976 catalog with the notation subject to stock on hand. The Remington 1923 catalog lists the .38 Long Colt with both black powder and smokeless loads as well as a smokeless midrange load. These commercial loads utilized the Remington #1½ primer.36 The Peters Ammunition Catalog No. 40 (1925) listed both smokeless and semi-smokeless loads, as well as a midrange load with smokeless; both used 150-grain bullets.37

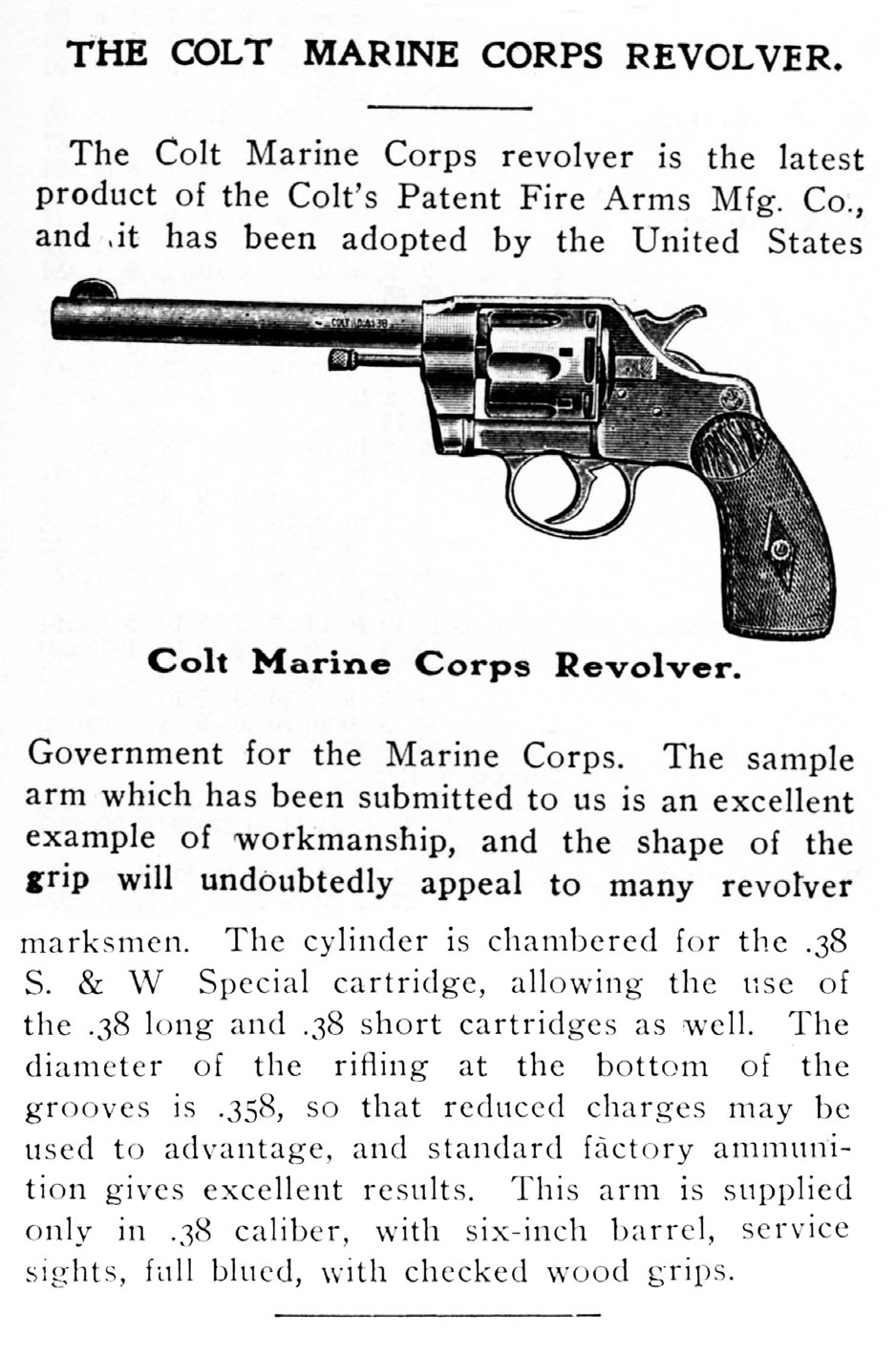

Hatcher stated that the Colt double-action military revolvers “…were really not very satisfactory arms.” The cylinder rotated to the left, which caused the cylinder to push away from the frame by the pawl as it rotated. As a result, they suffered from frequent failures of the chamber to line up correctly with the barrel, which leads to bullet shaving and inaccuracy. They also tended to break parts.38 The Colt double-action revolver Model of 1894 and the subsequent Models of 1896 and 1901, had a bore diameter of .363, with grooves at a depth of .003 making for a groove diameter of .369. The Model of 1903, reduced the bore diameter to .357 inch, making a groove diameter of .366 inch.39 Taylorson (1971) stated that the reason that the bore diameter was reduced was the introduction of smokeless-powder cartridges.40 Procurement of the .38 DA Colt Army revolvers is listed as 68,500 guns between 1892 and 1903.41

The Colt standard for the .38 prior to 1914, was .356/357 making for a probable groove diameter of .368 to .369.42 Venturino (1997) stated that the barrel groove diameters on Colt .38 revolvers (in the circa 1870-1900 time frame), was nominally .375 inch.43 Parsons listed the chamber dimensions for a Colt .38 as tapering from .381 at the rear to .359 inch at the mouth.44 Stebbins et al. (1961), stated that the service and commercial guns had unthroated chambers long enough to take a .357 Magnum cartridge.45 This work further recommended FFg black powder for this size case.46 Himmelwright and Mattern both also recommended FFg for this size case.47The original versions of the .38 Long Colt cartridge had bullet diameter in the .375- to .380-inch range and would have worked well in a .369 groove diameter barrel. The army is firing a .353- to .357-inch bullet through a .369-inch or larger groove diameter barrel. Apparently, this worked reasonably well with black powder, bumping-up the bullet to take the rifling. In FY1900 Frankford Arsenal began loading the .38 Army Ball cartridge with smokeless powder. The nominal charge was probably 3 grains of Laflin & Rand (later, DuPont after 1902, and Hercules after 1912) Bullseye.48 Bullseye was introduced in 1898, by Laflin & Rand and was a replacement for its Revolver Smokeless powder.49 This was about the time that the army became involved in the Philippine Insurrection.

There were worries about the “stopping power” of the .38 revolver expressed before and after its adoption. Parsons quoted the report of the service trial board, which recommended the adoption of the .38 DA Colt revolver, to the effect that the stopping power would be diminished; but it was unknown if it would still suffice. Parsons also quoted Robert Lee Bullard that personnel in the Philippines preferred .45 revolvers to the .38.52 Keith (1955) described both .38 Short Colt and .38 Long Colt as “…lacking in both accuracy and killing power.”53

I find it interesting that complaints about the .38 revolver and the .38 Colt Army cartridge do not begin until the army encountered “Juromentado” Moros after 1900. That was the year that the army began using smokeless powder to fire a .353 bullet through a .369 barrel. There was speculation that the .38 would lack stopping power, but no record of complaints arising from actual use until smokeless powder became the propellant. Suicide attacks are very difficult to stop as the enemy has to be killed or rendered unconscious in order to cease his attacks; witness the complaints of a lack of stopping power on the part of the .30-caliber service rifle, let alone the complaints against the .38 revolver.

Part 2: Testing the Hypothesis

The Test Revolvers

A Colt Army Special manufactured in 1926, with .38 Special chambers was used as a control for one smokeless load. It has a 6-inch barrel. This revolver had chamber mouths measuring .358 inch and the barrel was .354 inch in the grooves, which is the Colt standard for this revolver. It would not chamber a .357 Magnum case. This is a modern .38 Special chamber. The Army Special was the successor to the New Model Army, which was used by the U.S. Army and Marine Corps in .38 Long Colt. It is a product-improved version of the military revolvers, with most of the lock-work and barrel size issues fixed. It was introduced in 1908, was renamed the Official Police in 1928, and became one of the most successful police service revolvers of the twentieth-century.55

Assembling Test Ammunition

The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ standard (1993) for the .38 Long Colt is an overall length of 1.305 to 1.360 inches, with a maximum average pressure of 12,000 CUP Definitive proof is 19,000 CUP56 A specimen .38 Colt Navy with an outside lubricated bullet was loaded to an overall length of 1.355 inches.57 Similarly, a specimen .38 Colt Army with an inside lubricated bullet had an overall length of 1.366 inches.58 Hatcher (1935) listed the .38 Long Colt with an overall length of 1.32 inches with a 148-grain lead roundnose, hollowbase bullet. This is the smokeless load as the propellant charge is given as 3 grains of Bullseye with a pressure of 12,000 psi.59 Suydam showed specimen cartridges for .38 Colt Navy with overall lengths from 1.355 to 1.350 inches. He also showed specimen of the inside lubricated version of the .38 Long Colt with overall lengths from 1.340 to 1.374 inches.60

Himmelwright recommended a bullet temper (the ratio of tin-to lead) of 1:20 for smokeless powder and 1:30 for black powder.61 A 1:20 ratio produces a Brinell Hardness Number (BHN) around 10 and a 1:30 shows a BHN around 9.62 The exact hardness of the bullets used in military and commercial production of the .38 Long Colt is not known, but Himmelwright’s recommendations are used as a guide in constructing test ammunition.

In an effort to assemble test ammunition representative of ammunition produced in the early twentieth-century, Starline .38 Long Colt cases were selected. Magtech produces a 158-grain swaged bullet (#38A) that is .358 inch in diameter and has a dished, or recessed base. This bullet was selected as best representing the type of bullet used in military ammunition from 1892 to 1909. This bullet tested as a BHN 9 using a Lee Bullet Hardness tester. As a control, a 146-grain cast lead bullet (.358 inch in diameter) with a deep hollowbase was chosen to represent the military bullet in use beginning in 1909 and those used in commercial ammunition. This bullet was commercially cast by the now vanished Mid-Kansas Cast Bullet Company. This bullet tests out with a BHN of less than 8. It appears to be pure lead or something close to that. Additionally, some Speer 158-grain solid-base lead roundnose bullets #4648 were tested. It tested with a BHN of 8. All three bullets were loaded with either 15.4 grains of GOEX FFg black powder or 3 grains of Alliant Bullseye. Remington No. 1½ primers were used with both propellants. A TX-PT silhouette target was used for testing at 25 yards.

Range Results

The 158-grain LRNHB #BU38A with 3 grains of Bullseye averaged 737 fps out of the Pietta. Out of 10 rounds, eight hit the paper and six of those showed signs of tipping. This load fired out of the Uberti with its longer barrel averaged 786 fps. Out of 10 shots, all hit the target and two showed marginal stability. In the New Army Model 1896, 20 rounds were fired and all 20 hit the target point-on. In the Army Special with a 6-inch barrel, this load averaged 753 fps. Out of five rounds, all hit the target point-on. The performance in the Army Special shows that this load conforms similarly to the published performance of the military and commercial smokeless loads.

The Speer 158-grain LRN solid base was tested in the Pietta for velocity with 15.4 grains of GOEX FFg, which produced an average of 674 fps. It was tested for stability in the Uberti. Out of 10 shots, all hit the target and one showed definite tipping. In the New Army Model 1896, of 20 rounds that were fired, 15 hit the target, three were on the paper but off the target; and 12 showed evidence of tipping. These tests show that Himmelwright’s statement that black powder could bump-up undersized soft bullets to take the rifling is sometimes correct.

The 146-grain LRNFP hollowbase bullet was tested for stability in the Uberti. Two, five-shot groups were fired. Both were around 3 inches at 25 yards and no signs of stability problems were observed.

The accuracy of the New Army Model 1896, was overall poor. The best group with any ammunition was about chest-sized. Most were scattered widely over the target or beyond. The ammunition was tested at 25 yards firing from a sandbag and in single-action mode. After firing 30 rounds the barrel was leaded up.

Conclusion

Was the .38 Long Colt cartridge blamed for problems that resulted from a mismatch of the bullet diameter, use of smokeless powder and mechanical unreliability of the issued Colt New Army Revolvers? In a word, yes. The bullets apparently bumped-up sometimes when used with black powder, but when the change to smokeless occurred, the already poor accuracy of the New Model Army Double Action revolver suffered. The army was also aware of the issue as they changed the barrel specification to make it tighter in 1903, and in 1909, they deepened the hollow base in the bullet. I wonder how many Moros were missed entirely by poorly stabilized bullets fired from a revolver that could fire with its cylinder unlatched and which suffered from chronic parts breakage. The performance of the .38 Long Colt is only marginally less than the .38 Special standard velocity roundnose load. Hatcher described the .38 Special as, “…large enough for military use…”63

Did issuing .45’s increase “stopping power?” During the Insurrection in the Philippines, .45-caliber revolvers were issued to U.S. military and constabulary personnel after complaints about the .38 revolvers and cartridges appeared. Colt single action Army M1873s (often arsenal overhauled with barrels cut down to 5½ inches64) and Colt M1878 and M1902 Double Action revolvers were issued. Some 5000 M1878/M1902s were purchased for the Philippine Constabulary. These had 6-inch barrels.65

The .38 Long Colt cartridge fires a 148/152-grain lead roundnose bullet at a velocity around 755 fps for a muzzle energy of around 187 foot-pounds.66 The .45 Revolver Ball cartridge Model of 1882, as revised in 1887, was issued for use in the .45 revolvers sent to the Philippines. This is the same as the .45 Colt Government cartridge. This cartridge had a 226-grain flatnose lead bullet propelled by 26 grains of black powder.67 This combination would have produced a muzzle velocity around 735 fps for a muzzle energy of 271 foot-pounds.68 This is about a 44 percent increase over that produced by the .38 Long Colt.

Marshal & Sanow (1992) indicated that the .38 Special cartridge loaded with 158-grain roundnose bullets with muzzle velocities in the 704/767 fps range produced “one-shot stops,” as defined by them, around 52 percent of the time.69 The .45 Automatic cartridge with a 230-grain roundnose fully-jacketed bullet and muzzle velocities in the 799 to 837 fps range produced “one-shot stops” 60 to 64 percent of the time.70 This is around an 18 percent increase in “one-shot stops” over the .38 Special. The .45 Colt cartridge with a 255-grain lead roundnose bullet and a muzzle velocity of 706 fps produced “one-shot stops” around 69 percent of the time.71 That is about a 31 percent increase over the .38 Special. Given the similarities between the modern .38 Special with roundnose lead bullets, the .45 Auto and the modern .45 Colt with a lead roundnose bullet, to the cartridges in use during the Philippine Insurrection, the answer is probably “yes;” issuing the .45 over the .38 revolver increased the probability of successfully stopping an attacker. This higher probability is mostly due to the increased bullet energy of the larger cartridges.72

Sources

ANSI/SAAMI Z299.3-1993 Voluntary Industry Performance Standards for Pressure and Velocity of Centerfire Pistol and Revolver Ammunition for the Use of Commercial Manufacturers 1993

Barnes Frank C et al.: Cartridges of the World 14th Edition 2014

Butler David F: United States Firearms, The First Century 1776-1875. 1971

Hackley FW, Woodin WH, Scranton EL: History of Modern U.S. Military Small Arms Ammunition Volume I 1880-1939 1967

Hatcher Julian S: Textbook of Pistols and Revolvers, Their Ammunition, Ballistics and Use 1935

Himmelwright ALA: The Pistol and Revolver 1908

Hoyem George A: The History and Development of Small Arms Ammunition, Volume Three (British Sporting Rifle Cartridges) 2005

Garavaglia Louis A and Worman Charles C: Firearms of the American West 1866-1894 1985

Keith Elmer: Sixguns, The Standard Reference Work 1955

La Garde Louis A: Gunshot Injuries 2nd Edition 1916

Lyman Pistol & Revolver Handbook. 3rd Edition 2004

Marshall Evan P and Sanow Edwin J: Handgun Stopping Power, The Definitive Study 1992

Mattern John R: Handloading Ammunition 1926

McConaughy Miriam: History of Small Arms Ammunition (Army Ordnance Publication No. 1940) 1920

McDowell R. Bruce: Colt Conversions and Other Percussion Revolvers 1997

Neuschaefer Klaus: The Smokeless Powders of Laflin & Rand and their Fate 100 years after assimilation by DuPont 2007

Ordnance Pamphlet No. 1919: Description of the Colt’s Double Action Revolver Caliber .38 1917

Parsons John E: The Peacemaker and its Rivals, an Account of The Single Action Colt. 1950

Peters Ammunition Catalog No. 40 1925

Remington-UMC 1911-1912 Catalog

Remington 1923 Catalog

Report of the Chief of Ordnance, Appendix 13: Description of the Colt’s Double Action Revolver Army Model 1892 1893

Stebbins Henry M, Shay Albert JE and Hammond Oscar R.: Pistols, A Modern Encyclopedia 1961

Suydam Charles F: US Cartridges and their Handguns 1795-1975 1979

Taylorson A.W.F.: The Revolver 1889-1914 1971

UMC Illustrated Catalog of Ammunition 1905

Venturino Mike: Shooting Sixguns of the Old West 1997

Wikipedia: Juromentado accessed 6-28-2018

Endnotes

1Butler page 204

2Venturino page 111

3McDowell page 74

4COTW 14 pages 622-623, 628, 630 - Suydam page 94, 96

5McDowell page 71

6Suydam page 148

7Hatcher page 345

81955 ICI Catalog of Sporting Ammunition as reproduced in Hoyem page 187

9Suydam page 148 – Hatcher page 345 Experimentally Black Powder was tried in modern Starline solid head .38 Short Colt cases. Fifteen grains of either Goex FFg or FFFg filled the case to the top leaving no room for a bullet. Ten grains would fit with an inside lubricated 125 grain flat nose bullet seated normally. It’s possible that with a balloon head case and externally lubricated heeled bullet that 15 grains could be squeezed into the case with some compression. Fired in a Ruger Service-Six revolver with a 4-inch barrel and 38 Special chambers 10 grains of FFg registered an average muzzle velocity of 606 fps. Ten grains of FFFg registered an average muzzle velocity of 614 fps.

10McDowell page 67

11Garavaglia & Worman page 83

12McDowell page 232-234

13Butler page 113

14McDowell page 78

15Suydam page 152, 158

16McDowell pages 78, 232

17Suydam 158

18Suydam 158 – Hackley et al page 3

19Hackley et al page 3

20DuPont 1923 Powder Catalog page 8

21Author’s personal observation

22Hackley et al page 3

23Hatcher page 80

24Hackley et al pages 3-4

25Hackley et al page 4

26Hackley et al page 4

27Hackley et al page 4

28Suydam page 160

29Hackley et al page 4

30Le Garde, Cut-away drawing of bullet in Table 3 page 72 – Reproduced in Hatcher page 419.

31Hackley et al, Figure 7 page 5

32Report of the Chief of Ordnance Appendix 13 page 243

33Ordnance Pamphlet No. 1919 page 14

34Himmelwright page 130

35Hackley et al page 6, McConaughy pages 22-23, 39

36Remington 1923 Catalog pages 124-125, 173

37Peters Ammunition Catalog No.40 page 34

38Hatcher page 80, Taylorson 33-34

39Hatcher page 81

40Taylorson page 38

41Taylorson page 37-38

42Parsons page 126

43Venturino page 111

44Parsons 126

45Stebbins et al page 219

46Stebbins et al page 122

47Himmelwright page 133, Mattern page270

48Hackley et al page 6

49Neuschaefer page 38

50Wikipedia article accessed 6-28-2018

51La Garde page 69

52Parsons page 79, 82-83

53Keith page 277

54Hatcher page 81

55Taylorson page 45

56ANSI/SAAMI Z299.3-1993 pages 12, 37 and 158

57Hackley et al page 3

58Hackley et al page 4

59Hatcher page 350

60Suydam pages 158, 160

61Himmelwright page 131

62Lyman 3rd page 79

63Hatcher page 351

64Garavaglia & Worman page 96

65Taylorson 29

66McConaughy page 23

67Hackley et al page 11

68Hatcher page 371

69Marshall & Sanow page 55

70Marshall & Sanow page 92

71Marshall & Sanow page 102

72La Garde page 96