Who Was Albert F. Mitchell?

feature By: Robert Saathoff | November, 20

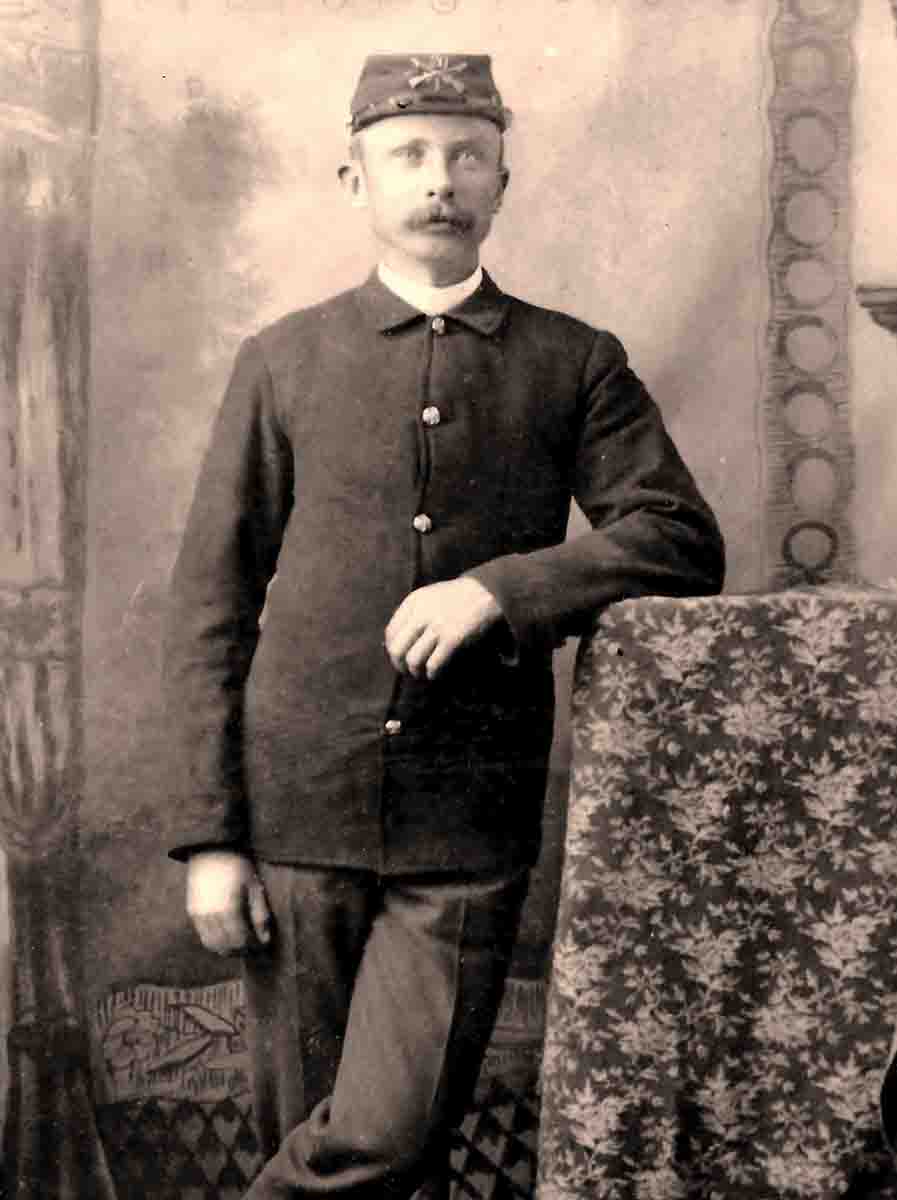

Albert F. Mitchell (aka “Elbert” and “Alfred” in various Civil War records) was probably born and raised around Saratoga Springs, New York. From court records, he is listed as a village trustee. He was buried in Greenridge Cemetery in Saratoga Springs with his wife, Cordelia.

On May 11, 1861, at the age of 18, Mitchell enlisted in the Union Army at Elizabethtown, New York. When arriving in New York City, he was mustered in on June 3, 1861. He was to serve two years and was assigned to the 38th Regiment, New York State Infantry and placed in Company K. The leader of Company K was Captain Samuel Dwyer who was later killed at the Battle of Williamsburg. The 38th Regiment was also known as the Second Scott Life Guard for General Winfield Scott, who at that time, lead the Union Army. On June 19, they were issued altered muskets and began their journey towards Washington D.C., arriving on June 21, encamping on Meridian Hill for training. They were issued four balls with powder but then were not given a chance to use them. President Abraham Lincoln and General Scott reviewed the regiment in front of the White House on July 4, 1861. The day of July 7, the regiment exchanged arms at the Washington Arsenal and began their journey towards Manassas Junction and Bull Run Creek. Eventually, they encamped at Centreville and two days later, on July 21, engaged the South at the “Stone Bridge” over Bull Run Creek. This was one of the first encounters of the battle of the first Bull Run. There, they fought gallantly and repulsed the opposition three times, taking heavy losses and eventually were overrun in the late afternoon.

New York State Military Museum

During the July 21 engagement against the opposition at the first battle of Bull Run, the 38th Regiment lost 128 killed, wounded and missing before retreating back to Washington. In August and September of that year, the regiment was employed in construction work at Forts Ward and Lyons with Howard’s brigade and in October the regiment was assigned to Sedgwick’s brigade, Heintzelman’s division. The winter camp was established in October 1861, on the old Fairfax road and occupied until March 1862, when, with the 2nd Brigade, 3rd Division, 3rd Corps, the regiment embarked for Fortress Monroe. The 38th participated in the siege of Yorktown and the battle of Williamsburg, where the loss to command was 88 killed, wounded and missing. They shared in the engagement at Fair Oaks and in the Seven Days’ Battle after which it encamped at Harrison’s landing until August 15 of 1862. From there, the regiment moved to Yorktown and Alexandria; were active at the second Bull Run and a day later at Chantilly. They reached Falmouth, Virginia on Nov. 25, and engaged the South at Fredericksburg, losing 133 members killed, wounded and missing.

Civil War Index, New York State Military Museum

As you can see, Albert definitely “Saw the Elephant” and somewhere in those battles, suffered a stomach wound. He probably suffered his wound at the Battle of Chantilly where 26 soldiers are listed as wounded and this battle took place about three months before he was mustered out. After Fredericksburg, the 38th Regiment was then moved back to Washington and set up defenses of the Capital. The battle of Fredericksburg wasn’t fought until after Albert was mustered out. He was mustered out of the military on December 10, 1862, from a hospital in Providence, Rhode Island, and began receiving a government payment of $4 per month for his injuries.

Civil War in the East

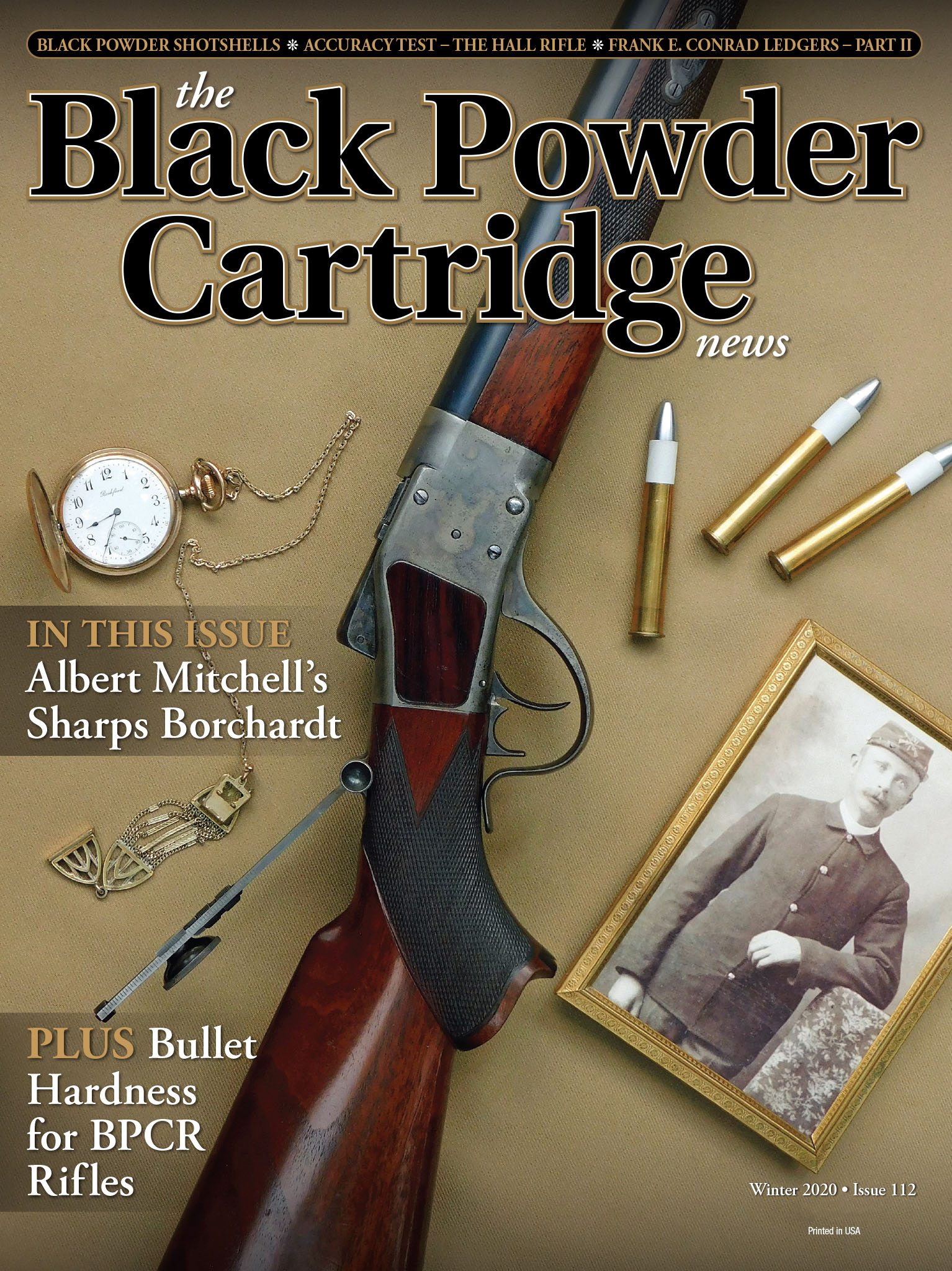

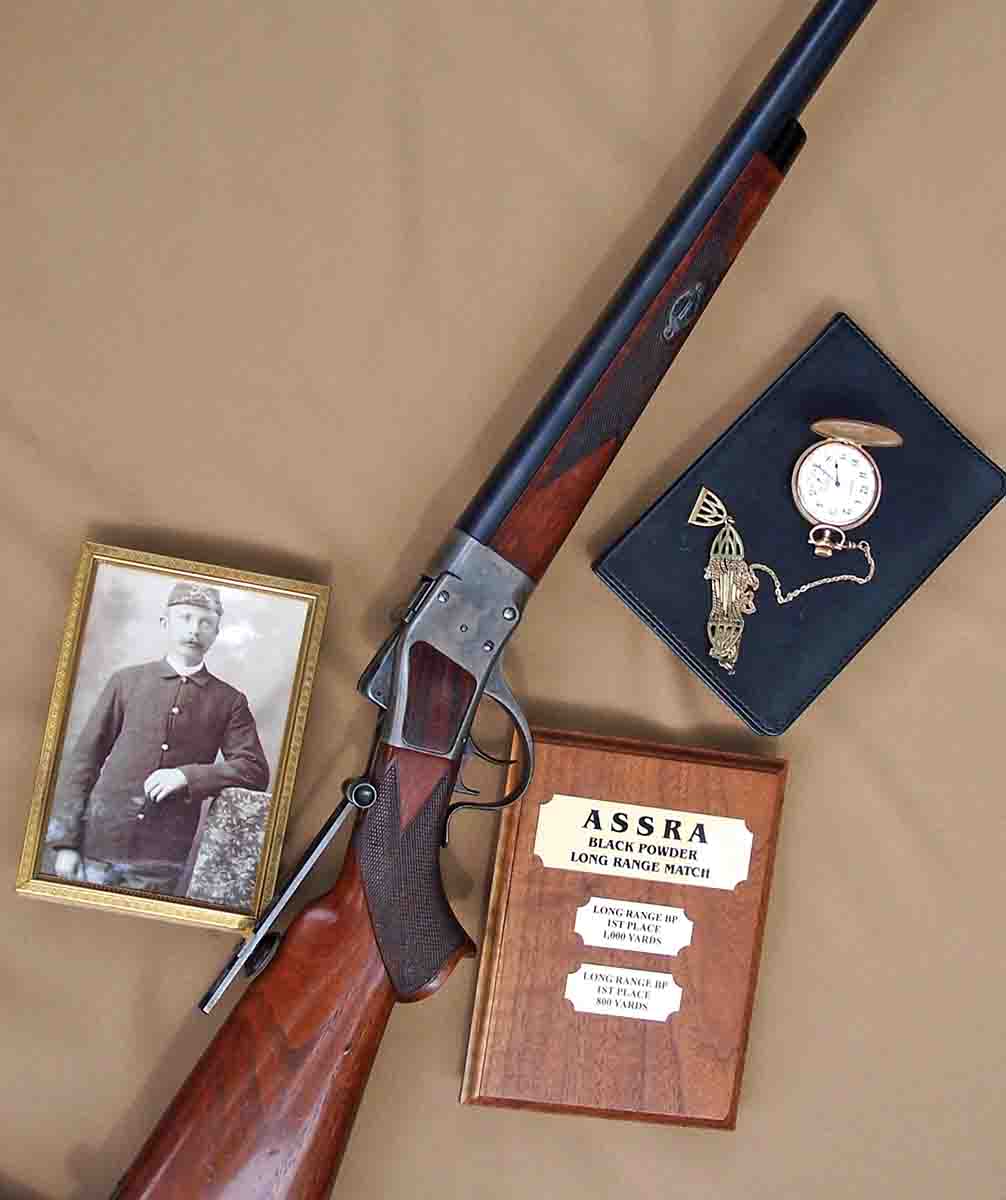

The rifle has a wind gauge globe front sight with spirit level and provision for a rear barrel sight. The barrel has the trademark “Old Reliable” and the Bridgeport, Connecticut, barrel address. It has a wedge-fitted, checkered forearm numbered to the gun with ebony forend cap and attractive celluloid faux rosewood panels on the sides of the action. There is a matching serial number on the right side of the breechblock with the main serial number on the bottom of the action between the trigger and the patent marking. A long-range tang sight is fitted to the integral base on the upper tang and also has the heel position base inlet into the top of the stock. The pistol grip buttstock has the curled grip tip with an ebony insert, the standard Sharps checkered grip along with a checkered hard rubber buttplate without the factory monogram. There were only 230 of these rifles were ever built by the Sharps Rifle Company.

Not too long ago, I became owner of Albert’s Borchardt rifle. After doing a little research about him from the documentation letter supplied with the rifle, I became very interested in who this man was. He must have become a well-respected man in Saratoga Springs to be elected as a village trustee and made secretary of the Saratoga Rifle Club. As a long-range black powder target shooter myself, one wonders why Albert took to long range shooting? Was it the smell of black powder that he encountered at an early age from his military service? Maybe it was a desire to shoot long distances that he may have seen while engaging the opposition? As the records show, the rifle was purchased in the spring of 1879. Did he have a desire to compete against other shooters for a spot on the Creedmoor rifle team or was this a popular event for shooters at the Saratoga Rifle Club? By the end of 1877, the Creedmoor matches were basically over and there was no match in 1878. The match in 1879 was unattended by other countries and the long-range matches that followed were by militias from various countries shooting against one another. Only Albert knew what moved him to buy this rifle.

The next job was to develop a working load with paper patched bullets. I first tried a dummy .459-inch grease groove bullet loaded in one of my cases but as expected, it would not fit in the chamber, as these rifles were made with what we know today as a tight paper patch chamber. I have a paper patch mould that casts a bullet at .455 inch and I wrapped the bullets with original patching paper made by the Crane Paper Company, which was used by shooters back then. The Crane Paper Company made two thicknesses of paper for patching. One of their papers has a thickness at .001 inch and one at .0015 inch. I had procured some of the .001-inch paper and it came in sheets that are 24 by 30 inches so I can get a little over 100 patches per sheet. I am surprised at how uniform the paper is for thickness and the condition it is in for being over 100 years old. The bullet patched with this paper mics at .459 inch and just enters the chamber but will not enter the muzzle of the rifle. Evidently, the Sharps factory workers lapped a taper in the barrel of these fine target rifles. I trimmed .45 caliber Norma Basic brass to 2.415, drop-tubed a full case of 1Fg Swiss powder into one of them and it weighed 101 grains. With a paper patch bullet seated 1/10-inch and some compression, I could be shooting close to 100 grains of powder. This rifle weighs right at 10 pounds and feels like a feather compared to my 12½-pound Borchardt target rifle that I typically use for long-range matches.

One of the things I tried was to develop a load that used less powder than the shooters used back in the Creedmoor days. I used two .060-inch fiber wads to reduce case capacity and that allowed me to have only 88 grains of 1Fg powder in the case. It didn’t take long to get a 200-yard sight setting at my local range and I then took the rifle and 20 loads to the practice day before the Harris, Minnesota, long-range match in August of 2019. The Harris long-range relays are all fired from the 1,000-yard line today, rather than the traditional 800, 900, and 1,000 yards. Using sight settings from my other .45 2-4/10 rifle, I was on target within three shots, but I could not hold all my shots on paper. There is more work that needs to be done on load development. During the firing of those 20 rounds that I made up, it was apparent that the recoil was quite severe, even with only 88 grains of powder. Remember, these rifles had to weigh at 10 pounds or under. I can see why many of the shooters used the supine or “back position” when shooting the Creedmoor matches. Part of the reason was to give them a steadier position, but it was also an excellent way to manage recoil. In fact, in an 1880 essay of the 1879 Creedmoor match by Edwin Perry, he noted that only one shooter out of 33 did not shoot from the supine position.

I plan to continue shooting this rifle on a casual basis in the way it was intended. Knowing the history it carries from the era of long-range matches gives me a little chill, knowing that at one time a Civil War veteran owned this rifle and had the same interests as I do today. It would be great to do some time travel and watch Albert shoot this beautiful rifle on a range back in New York, or to sit around in the evening and listen to the stories he could tell. It must have been quite a rush as an 18-year-old, standing in his dark blue coat and sky-blue pants while listening to the speeches on Broadstreet. Think of the pride he must have felt marching off to war as Captain Dywer gave the order to head to the awaiting steamer, as spectators lined the streets, waving flags and hankies during this grand parade.

In 2024, it will be the 150th Anniversary of the first Creedmoor match and there is a planned event to replicate it in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. It is still a long way off for a man of my age, but it could certainly be a goal to take this rifle and once again, shoot it like it was meant to be, in a Creedmoor match against some Rigby muzzleloaders.