Spence Wolf

And the Old Warrior

feature By: Kenny Durham | December, 17

What comes to mind when one hears the finale from the William Tell Overture? “Hi-Ho Silver, The Lone Ranger Rides Again!” Okay, another expression. What about the term “Trapdoor”? Maybe to a few, it conjures up

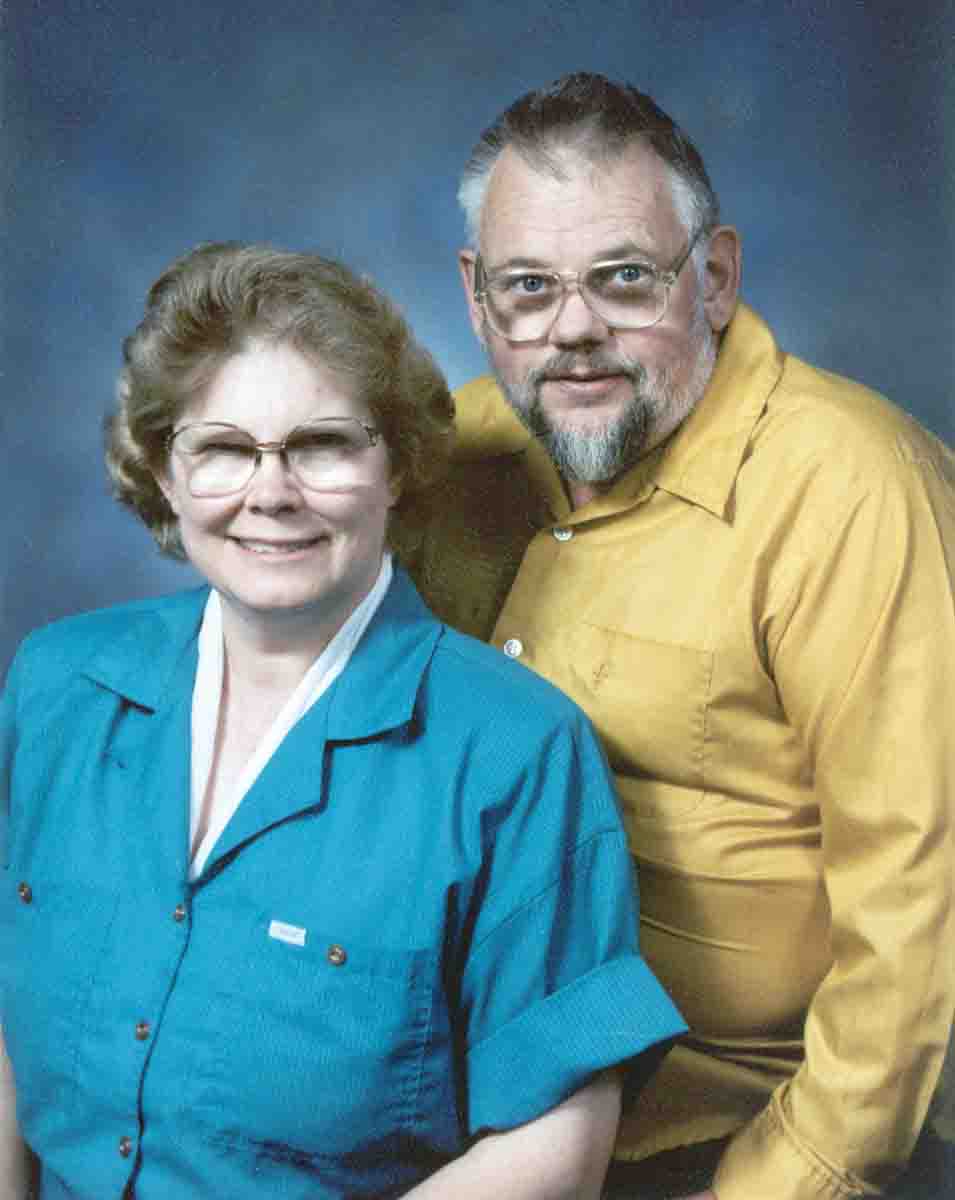

In 1975, Spence Wolf purchased his first .45-70 Springfield Trapdoor rifle, which he proudly referred to as the “Old Warrior.” Like most of us, Spence had some knowledge of Trapdoors and knew that his newly acquired rifle, equipped with the Buffington sight, was designed for shooting 500-grain bullets atop 70 grains of black powder. Also, like most of us, that’s about all he knew. Spence acquired some 500-grain lead bullets, seated them into cartridges loaded with black powder and headed for the range. His results were dismal with groups measuring around five feet at 100 yards. He was aware of the history of these old rifles and accuracy to which they had been fired in the past, so when his rifle and the loads that he had assembled scattered bullets all over the place he was sorely disappointed. Next, Spence tried loading the cartridges with smokeless powder but the groups did not improve. Believing that whatever accuracy the Old Warrior had once possessed had faded with the passing of the cavalry, Spence put the rifle away and went on with other projects. Then in 1988 a funny thing happened. At a gun show Spence came across some original .45-70 UMC, military contract black powder ammunition loaded for the Springfield rifle. He purchased 25 or 30 rounds of the old ammunition to play with in the “Old Warrior.” To his astonishment, with the UMC ammunition he put five shots in a group measuring three inches at 100 yards! The old rifle really would shoot after all. Spence surmised that the key to accuracy is finding how to craft the ammunition as it had been created in the past. But learning how to recreate the original arsenal loadings would send Spence and Pat Wolf on a journey lasting three years, while consuming many pounds of black powder, lead and tin in 15 original .45-70 Springfield rifles and carbines. At the end of the journey, Spence and Pat Wolf left for us their affection for the “Old Warrior” and an invaluable resource, “Loading Cartridges for the Original .45-70 Springfield Rifle And Carbine.” The first edition of the book was printed in 1991. Sadly, Spence Wolf’s life was cut short by cancer in September 1993. Several years ago, I had the pleasure of meeting Pat Wolf and listening to how she and Spence accumulated the knowledge for writing the book. Also, Pat gave me two boxes of 35mm slides taken by Spence during their research and testing. Spence had plans to publish additional data on the .45-70 and .50-70 Trapdoor, but never got the opportunity. The few photos that Spence took during his research are included in this article.

Learning about the Old Warrior

Learning about the Arsenal Ammunition

Along with learning about rifles, even more time was spent with the study of the arsenal ammunition loaded for the .45-70 Springfield. Most of us are aware of two basic loads for the Trapdoor: a rifle load with a 500-

Various methods of case manufacturing were developing, too. The result was that ammunition went through several changes from 1873 until 1898 when the last .45-70 cartridges were manufactured at the Frankfort Arsenal. Additionally, many loads developed at the Frankfort Arsenal were contracted out to ammunition manufacturers. Spence read everything he could find on the subject of Trapdoors and spent much time shooting and testing old Government and commercial ammunition. He also disassembled original ammunition to check the powder, bullet design and alloy, bullet lube and flash hole size. In his own testing, only Arsenal or commercial ammunition loaded to Arsenal specifications had produced the accuracy and consistency he desired. Spence had finally arrived at the point where he knew what worked. Three years of research and digging through Arsenal records gave Spence ideas of what methods he should try to make the Springfield perform as it had in the past. The next part of the adventure would be to reproduce ammunition of the same quality.

Ammunition Testing

Spence had one goal: recreate ammunition as produced by the Government Arsenals in the 1880s. In his own words, “I wanted to discover how to construct the original-type cartridges, not tailored to a specific rifle; ammunition that would perform within the accuracy standards of 2 to 4 MOA in original three-groove barrels with the service sights.” This required many trips to the shooting range, so Spence and Pat turned a van into

Most of the ammunition preparation took place at the Wolf home where Spence’s loading bench and work benches looked pretty much like those of any other shooter. Some of the additions that Spence wanted to make in future editions of the book were to expand the data on special-purpose loads such as the three-ball guard load and others. The three-ball guard load was one of the most common special-purpose loads and used well into the 1900s. Spence’s research shows that in 1917 Remington was awarded a contract to produce 2,500,000 three-ball loads.

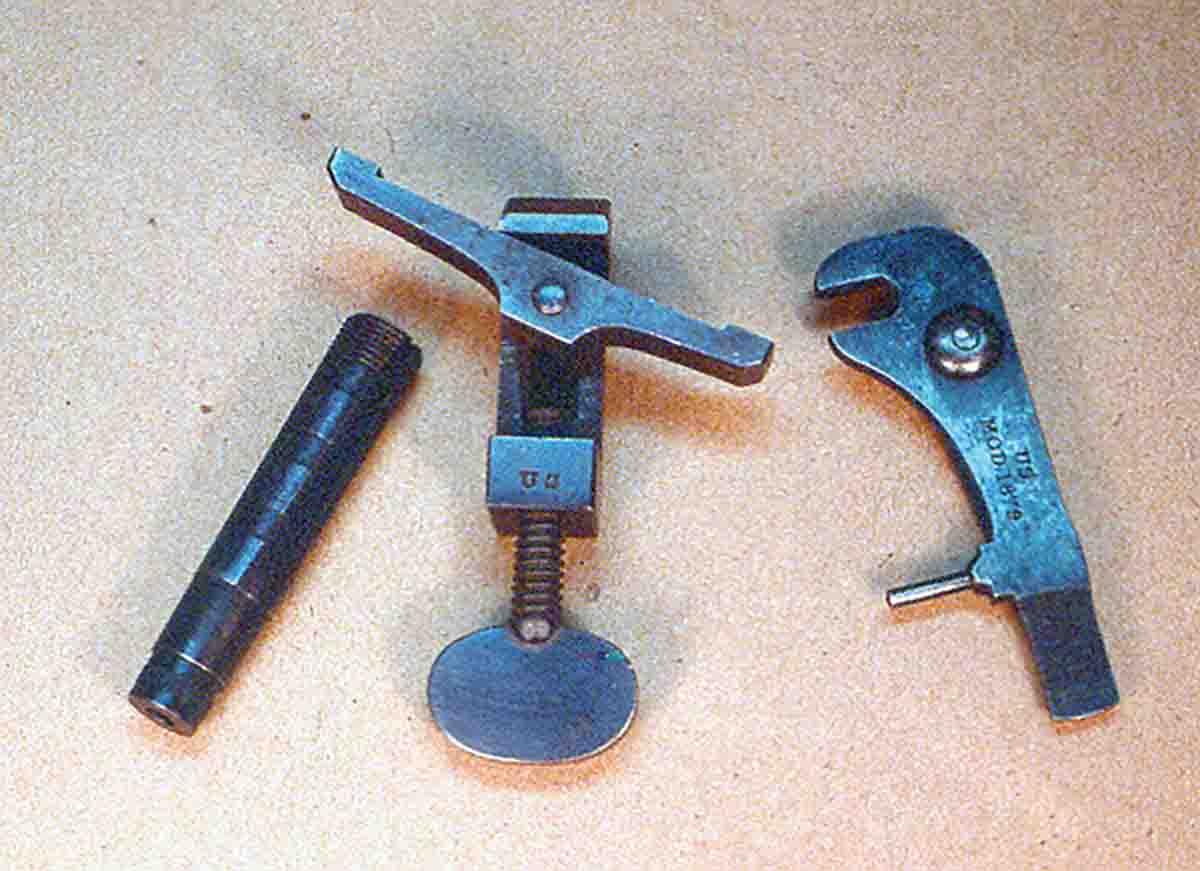

Spence had taken photos of the tools issued with each Trapdoor that included a headless shell extractor, mainspring vise, and a combination tool.

Soldiers were plagued by cartridge heads being pulled off by the extractor when soft, copper cases were used. The headless shell extractor was the only sure and quick way to remove the remaining portion of the case from the chamber. The last two photos from Spence’s work represent the culmination of Wolf’s research; an example of his re-created arsenal loads and a target showing the results.

Recreating Arsenal Ammunition

Spence’s biggest challenge came when he started testing 405-grain bullets. He learned that the flat-based 405-grain bullets used in sporting rifles did not shoot well in the Trapdoor. For Spence, getting acceptable

Many of the changes in the original arsenal loadings were attributable to refinements in the design of the brass case. For example, Spence wrote of the Model 1882 carbine load, “Similar to the Model 1873 carbine load, but loaded in the Model 1882 Pattern case.” In this example, it appears that the only difference was the case. Other changes in the arsenal loads were more significant. For instance, of the Model 1886 carbine load, Spence wrote, “First loaded in the Pattern 1882 case, and then in the Pattern 1888 case. The powder charge was about 55 grains. The cartridge length was changed from 2.55 inches to between 2.42 and 2.45 inches, thus omitting the filler wads that had caused some accuracy problems in the earlier carbine cartridges. Velocity was 1,150 to 1,200 fps over the production run period, from 1886 to 1898.” In this instance the brass was changed, the wads eliminated, the bullet seated deeper into the case and the velocity

Changes in the rifle ammunition represent even more radical changes. In 1873, the 405-grain bullet was standard for both the rifle and carbine. The rifle load consisted of 68 to 72 grains of powder loaded to produce a velocity of 1,350 fps. In 1882, the Arsenal discontinued this load. However, Spence indicated the load was furnished by contractors after 1882. The Arsenal began producing the 1882 rifle load with the newly introduced Model 1881, 500-grain bullet. The cartridge was loaded to an overall length of 2.79 to 2.82 inches and a velocity of 1,280 to 1,315 fps. Arsenal production was from 1882 to 1888. In 1888, the rifle load was updated by switching to the Model 1888 pattern case and continued for the next ten years. Then in 1898, the rifle load was changed to smokeless powder and produced by the Arsenal in limited quantities during the year. Spence indicated that in 1898, .45-70 ammunition production was turned over to contract and commercial companies to allow the Frankfort Arsenal to concentrate on the new .30 Army (.30-40 Krag) cartridge. Given the above-mentioned variety of loads, Spence had quite a pile to sort through in order to determine just what it was that he wanted to recreate! The process for him was somewhat simplified due to the

For the Trapdoor carbine, Spence developed loads to duplicate the Model 1873 and Model 1882 Arsenal load (the only difference being a change in the case) and the aforementioned Model 1886 carbine load. For the Trapdoor rifle, Spence developed loads to duplicate the Model 1873 which uses the 405-grain bullet, the Model 1882 and Model 1888 which uses the 500-grain bullet, and the Model 1889 which also uses the 500-grain bullet, but with smokeless powder. Not only did Spence Wolf succeed in recreating the Arsenal loads but went on to provide loading data that included FFg and FFFg black powder, smokeless powder data that produced the same ballistics as black powder, and duplex load data where applicable. So, even if a shooter chooses not to shoot black powder in their Trapdoor, the accuracy that the rifle is capable of delivering can still be achieved. Personally, I can’t imagine not wanting to shoot black powder in a Trapdoor, but I’ve heard those people exist!

Recreating the Arsenal Loads using Spence Wolf’s Methods

In order to be able to write this article from a knowledgeable base, .45-70 ammunition needed to be loaded and shot just as Spence had outlined in his book. I have been shooting my own Model 1884 Trapdoor for

For testing, three Arsenal loads were chosen to recreate: the 1873 rifle, 1888 rifle, and 1886 carbine. Testing consisted of loading and shooting the ammunition in six Trapdoors, two rifles, three carbines and an Officer’s Model reproduction. Concerning the firearms, however, a little bit different tack was taken than Spence. In the time that has passed since Spence left us, two new Trapdoors have arrived in the form of the 1873 rifle and carbine made by Pedersoli. In my testing, a Model 1884 Springfield rifle, two Model 1879 Springfield carbines, a Model 1873 Pedersoli rifle from Navy Arms Company, a Model 1873 Pedersoli carbine from Dixie Gun Works, and an 1875 H&R Officers Model were used. With these six Trapdoors, great fun was had filling the air with smoke.

Case Preparation

Taking all of this into consideration, a supply of used Winchester .45-70 brass that had been fired many times in other rifles was gathered. These particular cases were chosen because they all needed to be trimmed to a length of 2.105 inches that Spence specified in the book. According to Spence, the length of 2.105 inches is absolutely necessary to obtain the proper crimp. Additionally, W-W .45-70 cases have the greatest powder capacity due to thinner walls. Spence noted that the W-W case is very similar to the Frankfort Arsenal Model 1888 case. The cases were full-length resized, trimmed to 2.105 inches, flash holes drilled out to .096 inch and primed with Federal 215 primers.

Bullets

As mentioned earlier, I acquired an 1881, 500-grain mould from SAECO and a Lee 405-grain hollowbase 1873 mould from Wolf’s Western Traders.

The 1881 bullet measured .460 inch as cast and the 1873 measured .462 inch from the mould. The bullets were lubed with 50:50 olive oil/beeswax, which Spence refers to as JSW lube. I have personally used this lube for many years and it works well as a general-purpose, black powder bullet lube. It also works fine for smokeless powder loads. The lube was applied in a SAECO Lube/Sizer using a .460 die.

Loading Dies

Black Powder – Charging the Cases

Determining the powder charge for any of the three loadings that I tested was simple. I used the nominal 55 grains of FFg black powder for the Model 1886 carbine loading and 70 grains of FFg for the 1873 and 1888 rifle loadings. Wolf indicated from his testing that, “GOEX FFg black powder appeared to give the same velocity and pressure of original loading when the same weight of powder is used.” Spence conducted testing from 1988 into 1991 when the first issue of the book was published. I have some GOEX FFg that is dated 1996 that I felt would best represent and yield similar results as obtained by Wolf. When attempting to duplicate the arsenal loadings, the goal is to duplicate the trajectory of arsenal ammunition so as to regulate properly with the sight settings. Since the projectile has been duplicated by using the original bullet designs, the only remaining variable is the velocity. If ammunition registers within the allowable velocity range and is accurate to within two to four minutes of angle with 10-shot groups, then the goal has been achieved. Here are the velocity ranges for the ammunition that I was trying to duplicate: 1873 rifle load 1,350 fps; 1886 carbine load 1,150 to 1,200 fps; 1888 rifle load 1,280 to 1,315 fps.

Model 1873 Rifle Cartridge

The Model 1873 rifle cartridge is unique in that the powder is compressed more than in any of the other rifle loadings. The 70-grain charge, when compressed to the correct depth, measures .665 inch from the case mouth to the top of the charge. Prior to compression, distance from the case mouth to top of the charge measured .315 inch. The net result is that the powder charge has been compressed .350 inch, which has transformed the charge from loose powder into a solid pellet of powder grains that interlock. The .665 inch depth of compression corresponds with the Model 1873 bullet seating depth as well. I charged the cases by dropping the powder through a 30-inch long, brass drop-tube, since this is my standard black powder cartridge loading procedure. Due to the amount of compression required, however, little if any benefit is gained with the use of a drop-tube. Bullets were carefully seated with the die backed out of the press far enough to ensure that no crimping of the bullet would occur. Next, the loaded cartridge was run up into the Lee seating die with the seating stem removed and the bullet crimped into place. The proper die adjustment was determined by giving the die one-quarter turns and running the cartridge up into the die until the inside of the case mouth was firmly against the nose of the bullet without being impressed into the bullet nose. The finished cartridge overall length measured 2.52 inches. Spence lists the Arsenal overall length as 2.52 to 2.54 inches.

Model 1886 Carbine Cartridge

Model 1888 Rifle Cartridge

The Model 1888 was the black powder powerhouse load that gave the Old Warrior its real authority. A 500-grain bullet moving at 1,300 fps packs a wallop. The Model 1898 smokeless powder load boosted the velocity to 1,428 fps. Spence gives data for reproducing the Model 1898 load, but I chose to stick with black powder for my testing. Also, Wolf makes no mention of any of the black powder substitutes or replica black powder.

The adoption of a Model 1882-1888 load represented a major change in ammunition. The added 100 grains of bullet weight provided enough resistance that the hollow base could be eliminated, and the bullet seated shallower in the case, thereby reducing the amount of compression required. In loading, the 70-grain powder charge was compressed .260 inch. Although this amount of compression is less than the Model 1873 load, it is a significant amount and still results in the charge being compressed into a solid pellet with the grains tightly interlocked. Bullets were seated and crimped in separate operations as before. The Model 1881 bullet is crimped over the leading edge of the front driving band so the case mouth is firmly against the bullet nose.

At the Range

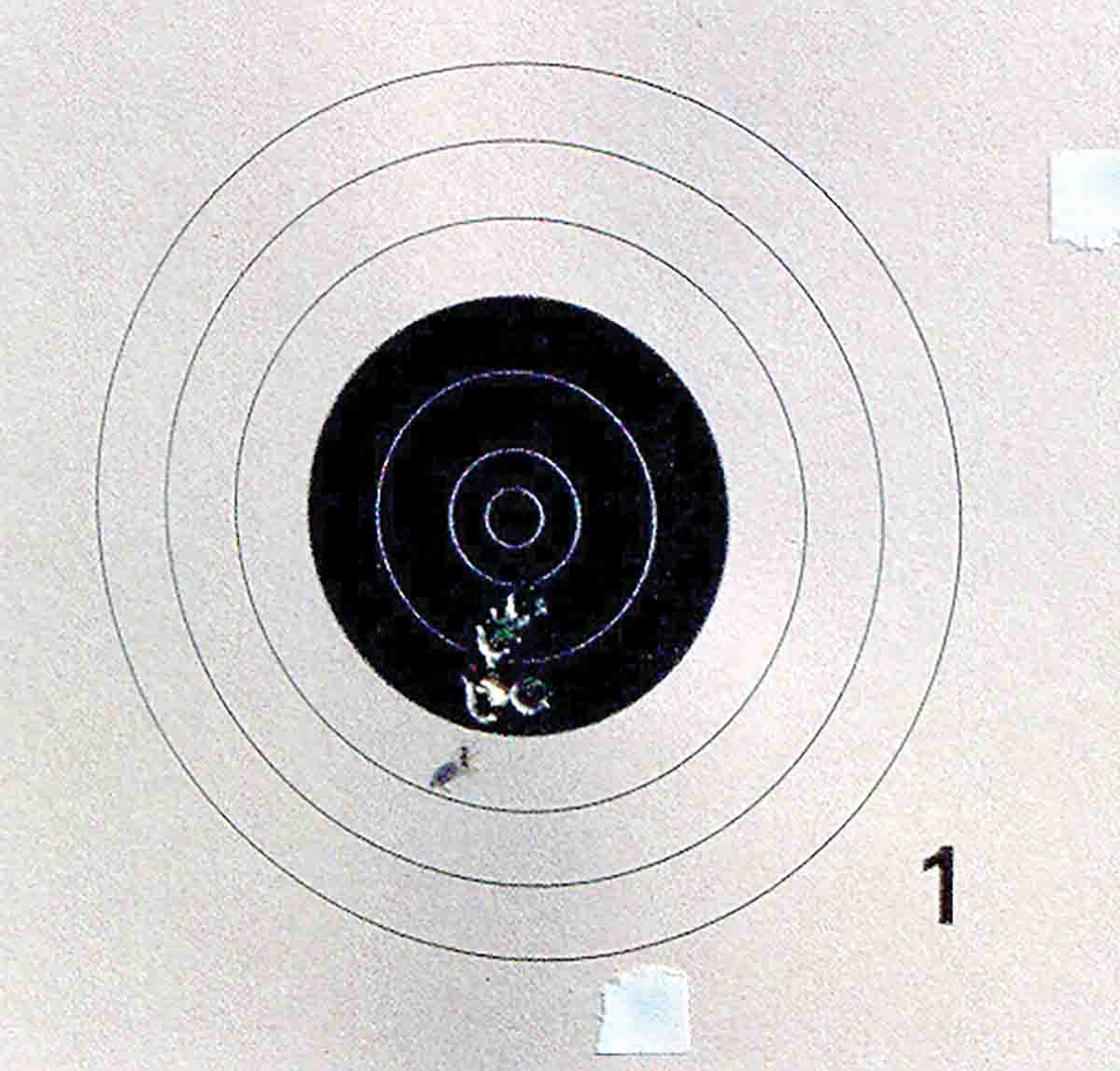

The Model 1873 rifle loads were fired in the original Model 1884 Springfield and Model 1873 Springfield reproduction rifles. Both rifles performed well but the original Springfield Model 1884 produced the best group. The target in figure 40 was fired at 100 yards from a bench rest. The one shot out of the group can be blamed on the stiff trigger pull of the rifle. The velocity of Model 1873 rifle ammunition averaged 1,364 fps in the Model 1884 rifle and 1,378 fps in the Model 1873 reproduction rifle. At 200 yards, accuracy with the original Springfield was noticeably better than from the reproduction. However, the ammunition performed well and was in all respects a good recreation of the Model 1873 rifle load.

The Model 1888 ammunition testing was next and as expected, proved to be more accurate than the Model 1873 loads. At 100 yards, the Model 1873 Pedersoli rifle produced a good 10-shot group. With the factory sights, the rifle printed to the right and high. To bring the group to center required an 8 o’clock hold at the edge of the black. Velocity from the Model 1873 reproduction with the Model 1888 load averaged 1,310 fps. The target was moved out to 200 yards and the firing continued. Here is where the original “Old Warrior” really shined with the Model 1888 load.

The photo (above left) shows how accurate that ammunition loaded using Spence Wolf’s methods could be. The 15-shot group was fired from a bench rest using the “battle” or “skirmish” setting of the Buffington sight. This required a 6 o’clock hold on the black to hit the center of the target; not a bad group at 200 yards with open, iron sights. To see how close the ammunition would register with the sight settings, I set the sight for 360 yards and fired at a steel plate known to be about 360 yards downrange. The bullet struck to the left and missed, but the elevation was right on the money.

Finally, the Model 1886 carbine ammunition was tested in three carbines and an H&R Officer’s Model. Due to fading light, groups were fired at 100 targets and a few shots were taken at the 360-yard steel plate to check the sight settings. The Pedersoli Model 1873 Trapdoor carbine produced a great five-shot group with a Model 1886 load.

Four shots are encompassed in the circle imposed over the photograph. Two shots in the white of the paper are hard to make out. The serial number of the original Model 1877 carbine is 380663, indicating that it was

The H&R 1875 Officer’s Model was used to test the Model 1886 carbine load only to see how the ammunition would perform. The H&R does not have the three-groove Springfield rifling nor military sights. Rather, the sights consist of a bead front and rear tang-style sight inletted into the wood. The rear sight is adjustable for elevation and windage but has no graduation markings. The group produced by the Officers Model was not a “match winner,” but certainly verifies that the Model 1886 ammunition loaded by Wolf’s methods is accurate and consistent in a variety of rifles.

The final testing of the Model 1886 Arsenal loading came about as a result of finding an 1877 carbine for sale in a local gun shop. It is an early 1877 model, serial 127031 from the 1880 production. All parts are original and correct except for the front sight. The bore is in good condition, but the last 1.5 inches at the muzzle shows much wear from the cleaning rod. A correct front sight blade was obtained and the remaining Model 1886 ammunition was fired in this carbine. Ironically, this epitomizes what Spence Wolf was trying to accomplish; duplicating the Arsenal loadings so that the ammunition will perform to specifications in any Springfield rifle or carbine.

At 100 yards, this newly acquired carbine produced the five-shot group shown in figure 22. This “Old Warrior” is a shooter! Next, the buckhorn sight was set for the 360-yard steel plate. The first shot struck low, but the second shot produced the splat of a bullet striking steel.

Wolf’s research was much more exhaustive than I have been able to describe in this article. Throughout the book, reading conclusions that represented months of research that were condensed into a few short sentences and paragraphs continually astonished me. Spence Wolf accomplished his goal of making the “Old Warrior” perform as it had during the late 1800s. The book that he and Pat published is a valuable resource as a loading manual and history book.

Pat Wolf continues to run Wolf’s Western Traders, the mail order and online business that sells this book and other Springfield rifle-related books along with a few other items. Contact Pat at Wolf’s Western Traders: (985) 882-3401, patwolf4570book@aol.com or www.4570book.info.