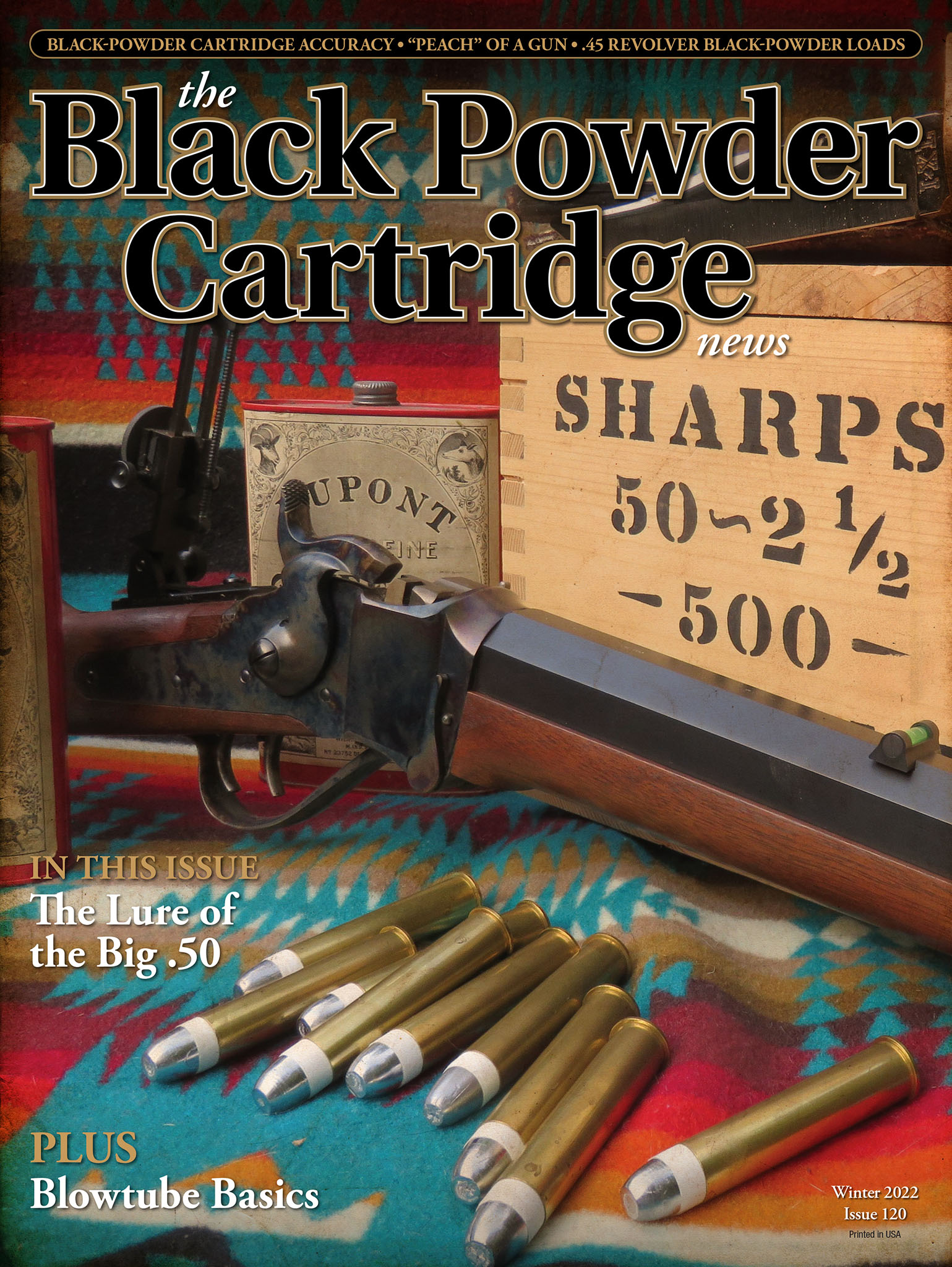

The Lure of the “Big Fifty”

feature By: Mike Nesbitt | December, 22

According to Frank Sellers in his book, Sharps Firearms, both the .50 2 inch and the .50 2½ inch were introduced almost at the same time, in July 1872. In Roy Marcot’s book, also called Sharps Firearms in Volume II, it is said that rifles for the .50 2-inch cartridge were produced between 1872 and 1874, with an estimated total of less than 50 guns. We can recognize that the .50 2 inch was made, but for now we’ll say no more about it.

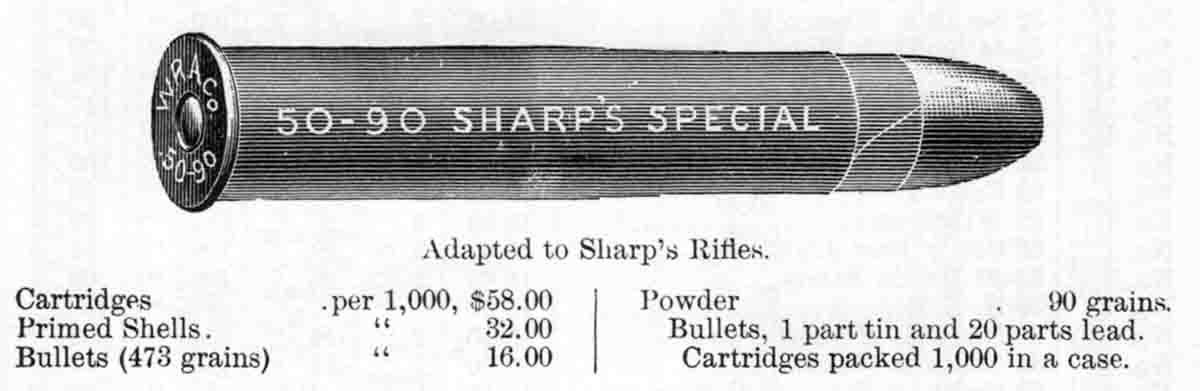

Now that our playing field is narrowed just to the .50 2½-inch cartridge, there is still a lot to talk about. It was already mentioned how this cartridge got its common name “.50-90” from a loading by U.M.C. But U.M.C. also provided this cartridge with other loadings including a .50-105-425 load and a .50-120-473 load. I have also heard of a .50-110-335 “Express” loading and in more than one instance in Roy Marcot’s excellent book, he refers to this cartridge as “the .50-110 Sharps.” Anyone who has loaded the .50 2½-inch cases can quickly agree that there is plenty of room in those cases for 120 grains of powder. With such variation available, every user of the Big .50 probably had their own favorite loadings.

Another buffalo hunter who used the Big .50 was George W. Reighard, who is also quoted in Getting A Stand. Reighard said that his rifles (he had two of them, both scope-sighted) used a 3½-inch shell. Of course, he was referring to the overall length of the loaded cartridges. He went on to say that the powder charge he used was 110 grains, adding how, with that load in his guns, he could kill a buffalo as far away as he could see it, providing the bullet hit in a vital spot.

The last buffalo hunter I’ll mention here who used the Big .50 is also one of my favorites, Jim White. These recollections come from the dictated memoirs of Oliver P. Hanna, which are also duplicated in Miles Gilbert’s book, Getting A Stand. Hanna said that White had three heavy Sharps rifles in .50 caliber, each weighing 16 pounds. The only Sharps caliber Hanna mentions is the Big .50, even though his own rifle was a .44-90 and is on display in Cody, Wyoming. White’s rifles disappeared after White was murdered in 1880, so getting any further data about his rifles ends there. Hanna did say, however, that White did some tremendous shooting with his rifles, enough to help the legends for this cartridge live on.

When in the hands of particularly good hunters, the .50-90 certainly performed with greatness; but that does not mean the Big .50 was a very popular cartridge. While we recognize that the Sharps sporting rifles were not made in large numbers, especially not when compared rifles such as the Model 1894 Winchester, we can’t be completely surprised at the low number of .50-90s that were built. Leaning on the research of Roy Marcot again, he showed the total production of Sharps Sporting rifles in .50-100 caliber from 1872 through 1878, to be only an estimated 320 guns. That, by any standards for production, is a very low number, but those rifles were more than enough for the Big .50 to achieve legendary status.

My own experience with the Big .50 stretches back over 40 years and since getting my first .50-90, my gun rack has not been without one.

For me, that first Big .50 is an outstanding one. It is a custom stocked “Gemmer,” which used a Shiloh Farmingdale action but stocked and finished by the young outfit called C. Sharps Arms. That was when they were located in Richland, Washington, a couple of years before making their move to Big Timber, Montana. Of course, I still have that rifle and it was not only my first .50-90, but it was also my first Sharps.

When I got that Gemmer, it came with several additional items such as a bullet mould, RCBS reloading dies, a file trim die, and one box of trimmed and loaded cartridges in BELL cases. I had a hunt to go on very soon after getting the gun, so I was taken to a range close by the C. Sharps Arms’ shop where some sighting-in could be done. That was successful and so was the hunt. With that Big .50, I dropped a blacktail doe with just one shot.

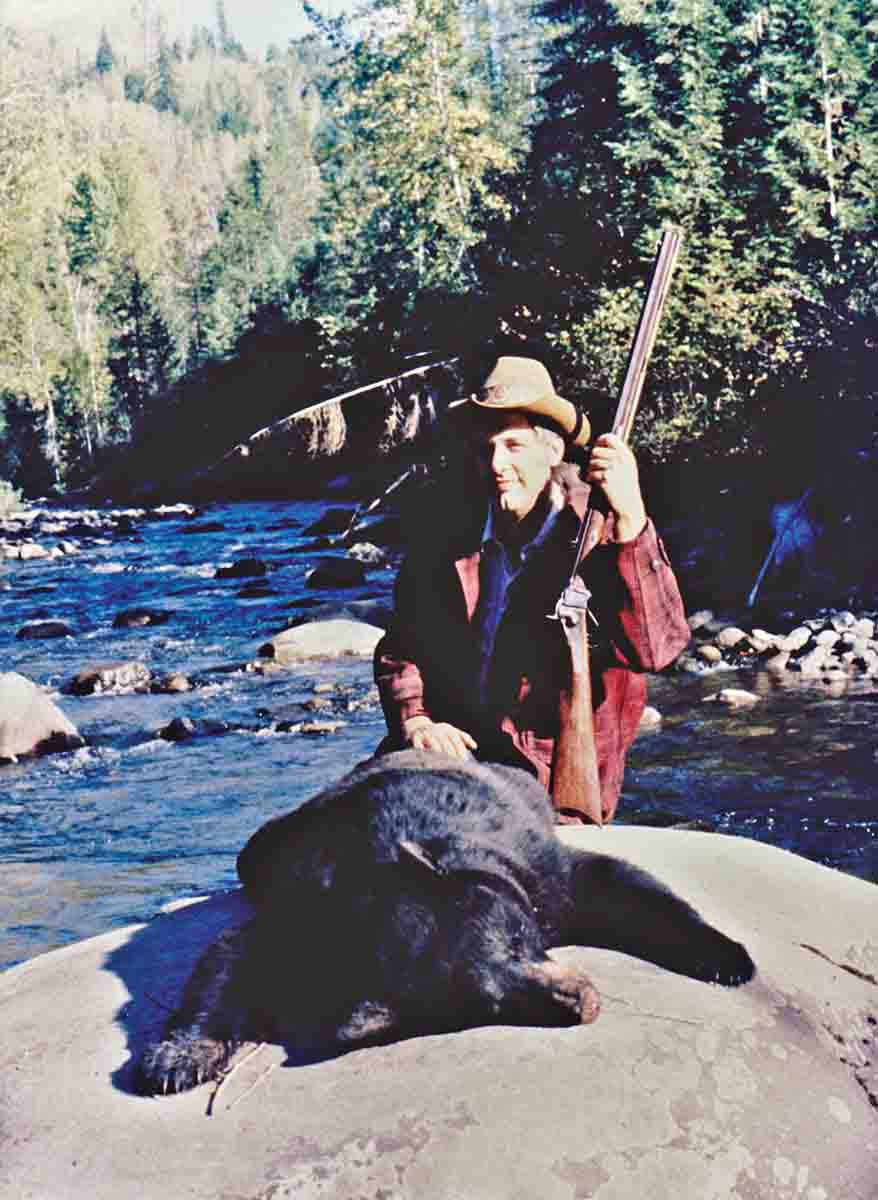

More hunting was done with that rifle, especially after getting some paper-patched bullets for it. I don’t recall getting or needing any more brass cases because I only used the gun for hunting. One of those hunts was for bear and I took a fair-sized black bear, up in the northern part of Washington state, with a 500-grain paper-patched bullet from an NEI mould. I have never seen a bear that was hit so hard!

That rifle taught me many things. One of those things was that although it has a 1:36-inch rate of twist, it seemed to fire everything I loaded into it very accurately. Of course, it still has its open sights and I never did shoot the gun at any distance beyond 100 yards. It was a hunting rifle and a beautiful one, but nothing more. It also taught me about the recoil of the Big .50, although that was never noticed when shooting at game. Let me point out that this Gemmer weighs only 9 pounds and it has the light or standard-weight barrel. The highest number of shots I fired with it in one setting was just 14 rounds and by then I was through!

So, for a Big .50 to do more shooting with, I will recommend a heavier rifle. I followed my own recommendations when getting the other .50-90 that I own. This is also from C. Sharps Arms, made at their shop in Big Timber, and it is a Hartford-style with a 30-inch No. 2 Heavy barrel, which gives this rifle a weight of 14¼ pounds. That’s much more like a rifle that a buffalo hunter would have selected. The barrel is a Badger with a 1:26-inch twist and is equipped with the Deluxe Mid-Range Vernier tang sight. This is a “shooter’s Big .50” although it still backs up with something like revenge in mind when it is fired with a good, full load.

Speaking of loads, I’ve never had much luck with using a Big .50 with reduced loads. If you have lighter loads in mind, get a .50-70 and enjoy it. I’m not putting the .50-70 in second place at all. If given the choice between a .50-70 and the bigger .50-90, I’d pick the .50-70 mainly because I feel it is a more “all-around” rifle. But it’s at the top end where the Big .50 takes over.

For Big .50 loads, I’ve always enjoyed trying to copy the old loadings. One that I had never tried until starting this story was the .50-105-425 loading that is mentioned in the Roy Marcot book. To me, that sounds like a tremendous deer and antelope load, so I used my KAL Sharps .50 mould adjusted down to drop 425-grain bullets and went to work. These 425-grain bullets have done very well for me when loaded in the .50-70 and that duplicates an old .50-70-425 sporting load.

One difference between my .50-70 loads and the loads tested with the Big .50 is that these 425-grain bullets with a diameter of .494 inch, are patched with two wraps of the patching paper from BACO but for the .50-90 they were patched with three wraps. The reason for the additional wrap was so the bullets would be held firmly in the cases.

I began triple-wrapping certain bullets for the Big .50 several years ago and the extra wrap has always been on the positive side. Elmer Keith used to mention triple-wrapping some of the bullets for his old .44-90, but he is the only other shooter I have heard of who used a triple-wrap on paper-patched bullets.

The first shot with one of the .50-105-425 loads hit right where the rifle was aimed, very nice, and the high velocity certainly got our attention, 1,464 feet per second (fps). (The chronograph was set out at 25 or 30 feet in front of the shooting bench so smoke would not cause errors.) Only five rounds of that load were prepared and they were fired while only blow-tubing between shots. The group was not the best, which makes me wonder if the hits would have been tighter if we had wiped the bore between shots. As it was, those five shots were a good place to start from and the average velocity for the load was an impressive 1,457 fps.

Some loads duplicating the old Sharps loading of .50-100-473 were tried, using 100 grains of Olde Eynsford powder and those gave an average speed of 1,323 fps. Those loads used bullets from the same KAL mould, simply adjusted out to drop the 473-grain bullets.

Another mould from KAL is for the .505 Gibbs and I like to use that bullet because with the differently shaped noses, the loaded rounds can be identified at a glance. The .505 Gibbs mould is set to cast 500-grain bullets and these drop from the mould with a diameter of .492 inch so they were triple-wrapped like the 425-grain bullets. (KAL will make the moulds with the diameter you request.) When loaded over 105 grains of Olde Eynsford 1½ powder, the 500-grain bullets crossed the screens at an average 1,398 fps. That’s a powerful loading.

The six shots fired with the Ballard bullets and the 100 grains of Olde Eynsford 1½ Fg did produce the best group. That is not surprising and the Ballard mould could be adjusted to make slightly heavier bullets, just to get some tighter grouping. As it was, Jerry shot those loads into the black on the 100-yard target in a very definite “meat-making” manner.

After doing our recent shooting with the Big .50, the lure of this big Sharps cartridge is calling even more. We will do more shooting, most probably with some heavier bullets and bigger powder charges. There might even be more hunting done with those loads as, after all, the Big .50 was designed as a hunting cartridge.

The lure of the Big .50 for Sharps shooters is really quite a call. The legendary .50-90 Sharps is not the most powerful black-powder cartridge, it isn’t the most accurate, but in all other regards it is certainly is “the most.” If you hear the Big .50 call, answer it, because there is no other way to satisfy the lure – and – the Big .50 has its own way of answering back.