Blowtube Basics

feature By: Steve Garbe | December, 22

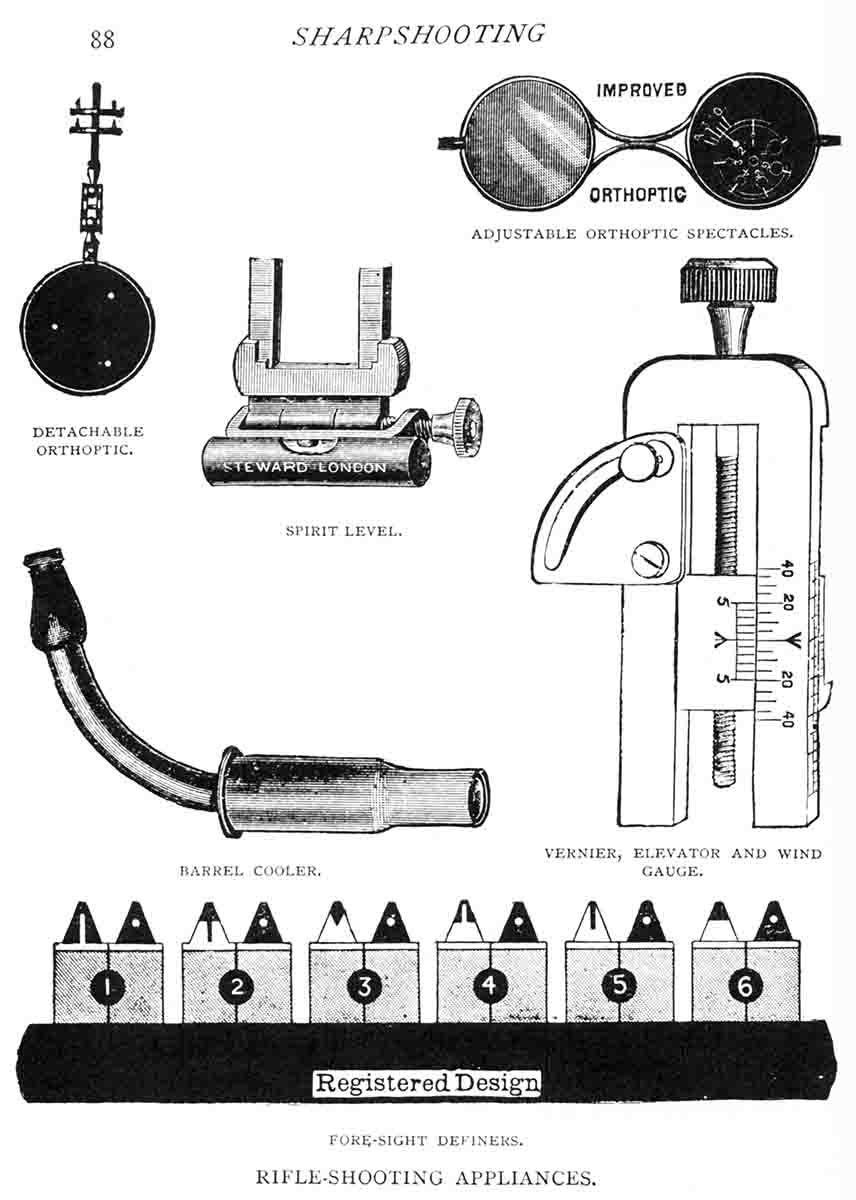

Having grown-up shooting muzzleloaders, my first inclination to deal with the fouling from the Curtis and Harvey (or as some called it, “Scurvey and Heartless” after cleaning its caked fouling from a barrel) and GOI black powder we had then, was to blow down the barrel from the muzzle like we did to soften fouling in our muzzle loaders. Obviously, range etiquette was not then what it is now, as I think doing this on a range today would get one firmly escorted off the grounds. I didn’t like cleaning between shots, as it seemed cumbersome, although it did solve a multitude of problems. About this time, I read Greener’s book, Sharpshooting For Sport And War, and saw mention of the “barrel cooler” that English competitors had used in their military rifle shooting. When it rains, it pours and over the next several weeks I read an article in one of Gerald Kelver’s books on A.O. Niedner and his efforts when in the army at making the Trapdoor Springfield shoot. Niedner mentioned using a “blowing tube” made from a cartridge case to blow down the breech of the barrel to soften the fouling between shots. Off to the shop I went and soon had a .45-70 blowing tube made up to try the thing out in the 1881 Springfield I was shooting at the time.

Soon after rediscovering the merits of the blowtube, I happened to purchase at the Bozeman, Montana, gun show, a supply of vintage Curtis and Harvey “Diamond Grain” powder in 1Fg granulation. “Diamond Grain” was not the Curtis and Harvey that I was used to; this was a very good sporting-grade powder and highly regarded in its day. This was truly a revelation and coupled with the use of a blowtube, I started to get what even today we would regard as good accuracy in my black-powder breechloaders. Many guys simply wouldn’t believe that I wasn’t using a duplex load and still warned me about rusting a barrel. For the record, I have never rusted a barrel using a blowtube, but I have been careful not to blow in a barrel and then let it sit. I’m sure one could start some healthy rust if a wet barrel was neglected.

In doing some research for this article in my collection of Shooting and Fishing magazine, I ran across some letters from readers that showed that, even back in the day, the blowtube was not without controversy.

This is an excerpt from a letter to the editor from a subscriber in 1886, using the non-deplume “James Duane:”

“In conclusion, I wish to define my position in regard to non-cleaning matches rather more clearly than I did in my last letter. I do not wish to be understood as favoring the style of so-called “dirty shooting” as practiced at Creedmoor and elsewhere, principally in special military matches. This method is fully as undesirable as the detached bullet swap-brush system, and is by no means as efficacious. For the benefit of such of your readers who may not be familiar with the system I will describe it as briefly as possible. The marksman is furnished with an implement variously known as a “Chanter,” Breathing Tube,” etc.., made by drilling out the base of a shell and tapping a short nipple into it. To the other end of the nipple a short piece of flexible tubing is secured by a suitable coupling. The free end of the tubing is furnished with a mouthpiece like that of a cigar-holder. After the gun has been fired the shell of the “Chanter” is inserted in the chamber, the muzzle of the gun is supported on the toe of the boot to confine the air, and the shooter blows slowly through the tube to soften the powder residuum with moisture from the breath. After this rather amusing performance has been kept up a greater or less length of time, depending upon the temperature, and dryness of the atmosphere, the gun is reversed, the “Chanter” still being left in place, and the gun is then blown through from the muzzle. The “Chanter” is then removed, and, if the blowing has been kept up long enough, the gun is ready for another round. If not, the operation is repeated.

“It is evident that this style of dirty shooting is utterly “impractical.” Even the objectionable swab-brush is far preferable. It will do its work in half the time, and do it much better. In our hot, dry climate the powder residuum will sometimes cake hard with any known lubricant, and stripping of patches with the attendant leading will follow. Therefore, moisture to soften this hard crust must be supplied from some source. I believe it to be perfectly legitimate to moisten the barrel by breathing through it from the muzzle. This is perfectly practical, and, with proper chambering and ammunition, answers every purpose. A man carries his breath with him everywhere, and the muzzle of his gun is always accessible. If cleaning must be resorted to it can be done in a perfectly practical and satisfactory manner by employing a field cleaner, made of small lead sinker that will drop freely through the barrel, attached to which is a stout piece of cord. To the free end of the cord a piece of wet or oiled flannel is fastened. By dropping the sinker through the barrel from the breech the rag can be drawn through the barrel, sweeping all before it, and immediately your gun is clean as a whistle. This method has been employed on the plains in hot skirmishes with the Indians during a lull in the firing, and thus may be said to have stood the test of actual service.”

– James Duane

New York, N.Y.

So, it’s obvious that the much maligned “blowtube” has been with us for many years and is, like so many things about black-powder shooting, simply old technology rediscovered. What I’d like to go into now are some of the little tricks and requirements that I have learned over the years of using the blowtube in competition and in the field.

There are some big mistakes that I commonly see shooters make when using a blowtube. One, the mouthpiece on the blowtube is much too long. I know it is much more convenient to use a long, flexible mouthpiece, but the problem is that your breath simply condenses in the mouthpiece and doesn’t make it into the barrel, which is where we want it, softening the fouling. My blowtubes have mouthpieces that are typically 4 inches long, just long enough for me to use if I have my face up next to the rifle’s action. Making a mouthpiece from a stiff plastic tube, yellow in color, will also let you also use the blowtube as a “open bolt indicator,” as is required now on many ranges.

The second mistake is that shooters, after having used a blowtube, don’t give it a quick flip to shake out accumulated moisture. If allowed to build up over several shots, this moisture will be blown into the barrel and an off shot will occur, usually to twelve o’clock. This is the least that will happen; it is entirely possible that you will get an off-shot AND a stretched or separated case as well. Giving the blowtube a quick shake to throw out the excess moisture will keep this from happening and still keep fouling soft.

In the slug gun shooting world, it is imperative that one does everything the same way when loading these notoriously picky firearms. This is especially true for the manner in which you wipe one out. Use one extra wet patch, or not enough dry patches when cleaning and you can be guaranteed of an off-shot, generally high at twelve o’clock if the bore is wetter than it was for the previous shot. The same goes for your BPC rifle when using a blowtube. Blow more times than another or for a longer duration and you will get an off shot from fouling that is either too wet or too dry. Getting in the habit of counting the number of breaths you use and keeping the duration the same is very important to consistent accuracy.

The mouthpieces on my blowtubes are quite large in diameter; at least 3⁄8 inch and closer to ½ inch. Again, we are trying to get as much moist breath through the barrel as possible without it condensing in the mouthpiece. Also, we don’t want to have to work too hard to blow through the barrel as this simply serves to increase heart rate.

Staying hydrated is also important to getting good results from a blowtube. It goes without saying that if your mouth is dry, not much moisture will be passed down the blowtube. Drinking plenty of water during a match also serves to keep your eyesight up to par, as the eyes are the first thing to suffer when dehydration sets in.

I have used a blowtube when in the field, generally to clean between shots in the course of a hunt. However, do not blow in the barrel of your favorite hunting rifle, chamber a round and leave the barrel wet for any length of time. Even here in the dry Rocky Mountains, such behavior will ensure a rusted barrel in a matter of hours, if not minutes. I typically use a blowtube to clean out fouling and dry patch until the barrel is clean. My hunting rifles are sighted to be “ON” with the first shot out of a clean, dry barrel. One must know where succeeding shots will go, of course, but if the first shot is good, follow-ups are rarely necessary.

More than any other shooting appliance, the blowtube ensures consistency over a long string of shots. It’s a simple tool and has been with us for a long time, but it must be handled correctly for the best results. Hopefully, these tips will help in your quest for better practical accuracy in your black-powder cartridge rifle and add to your score in the next match.