Richard W. "Dick" Rock

feature By: Leo J. Remiger | December, 21

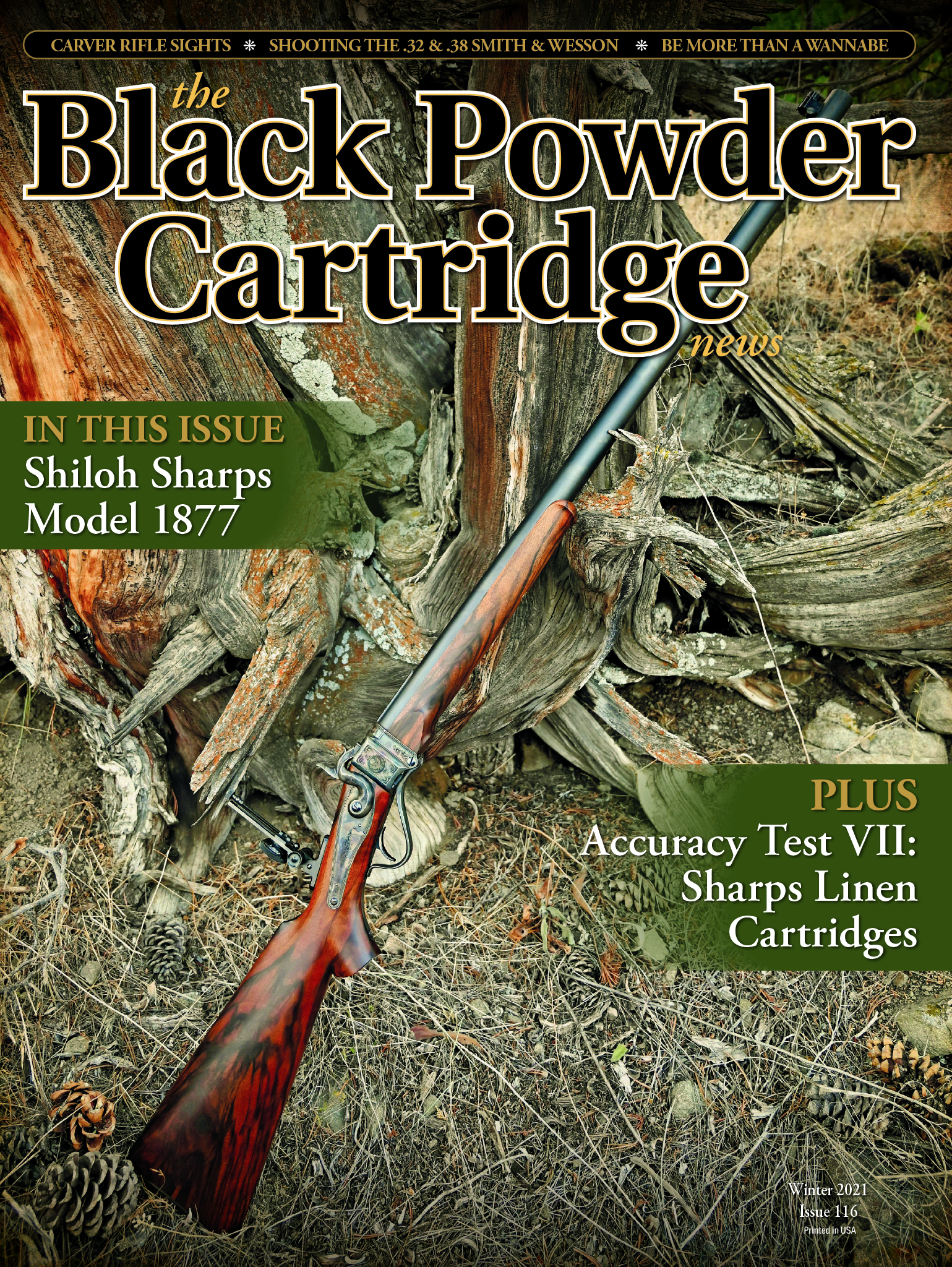

Rock was described as over six feet in height and built on good proportions. He was straight as a ramrod, wore his hair long and cultivated the military mustache and goatee. He was an expert on snowshoes and skis, upon which his ordinary gait was 16 miles per hour. It was a common exploit for him to run down game in the snow. His home at Henry’s Lake (Idaho) was filled with trophies of the chase, consisting of moose, elk, deer, buffalo and bear. He had six powerful Newfoundland-Shepherd mixed-breed dogs, which always followed him on the hunt and pulled a big sled or toboggan upon which the game was loaded.

About 1871, he established a homestead in southeastern Idaho Territory near the border with Montana Territory. His chosen spot was amid the soaring pines along the east shore of Henry’s Lake, north of Sawtelle Peak and west of Targhee Pass. He built up his ranch during the summers, while working as a guide, trapper or buffalo skinner the rest of the year. His ranch, located in Fremont County, eventually encompassed 2,000 acres.

In his article titled, “Dick Rock’s Zoo at Henry’s Lake,” Henry Bannon wrote the following:

“Both Dick Rock and Vic Smith were fine exponents of that hardy race of pioneers who pushed across the mountains a half century ago and delved into a region of game, the like of which will never be seen again on this continent.

“Dick Rock was an unusually hard worker, a fast traveler, wonderfully adept at snow shoeing and ate but little meat. Vic Smith did most of the hunting for the outfits that he and Rock would take into the mountains. Smith used a .38 caliber Winchester, Model ’73, and was one of the best and quickest shots that ever hunted in the West. He could hit an empty rifle shell thrown into the air and has been known to alight from his horse as grouse were rising from the ground and kill two with his rifle before they could get out of range. His favorite rifle was given to him by the Marquis de Mores, who was a well-known ranchman in Dakota. Medora was named for the wife of Mores.”

In 1902, The Anaconda Standard published an article titled, “Dick Rock, The Trapper, And His Odd Career,” and described the association of Dick Rock and Vic Smith as follows:

“In the fall of 1880 he was hired by Vic Smith, the veteran bear hunter, to skin buffalo north of Glendive on the Redwater. Rock skinned buffalo three years for Smith. He then went to Livingston, where he discovered a coal mine, which he sold to the late George Alderson for a snug sum.

“In the fall of 1883 the famous Marquis de Mores came to Big Timber and joined Vic Smith, who had acquired the reputation of being the champion rifle shot and boss hunter of Montana, on a bear hunt. They killed four bears, all large silver tips, in one week. On their return to Big Timber, Smith again met Rock and they renewed their old friendship and looked about for a location for a game ranch.

“Smith was the first person to scheme the catching of elk by chasing them on skis. In the five years that the two men were partners they caught and sold more than 300 elk alive. Smith was a big-hearted, generous sort of man with his money, while Rock was rather saving and careful in regard to financial matters. At the end of the five years Smith had what he started with, a cayuse and saddle and gun, while Rock, having saved his money, had $5,000 in the bank. Smith always guided the hunting parties, while Rock, who was a powerful man and a first class worker, ran the ranch. Rock claimed that he never got tired, while Smith was always tired. Rock was perhaps the best and swiftest man on skis in Montana. At the end of five years Smith and Rock dissolved their partnership, but not their friendship…

“Rock greatly disliked a reputation that was given him but to which he was not entitled. He frequently said he never was a scout for the government in any form, and did not know how the report that he was one started. His old-time partner, Vic Smith, was scout for Terry, Custer and Miles at the same time that Jack Conley, sheriff of Deer Lodge county, was packer and master of transportation.”

Their game ranch was no small-time operation. For about five years, Rock partnered in the wild game business with hunter and trapper Vic Smith, and they hired men to build the corrals. Eventually, the two parted company, though they remained friends. Rock kept at it.

He would collect scores of elk at a time and build crates in which to carry them by wagon to the rail line at Bozeman, Montana (which became a state in 1889). It was an arduous journey over rough roads and it was also a tedious operation, since he could take only two elk in each wagon, tolling many trips before his entire herd was amassed at the freight yard. From Bozeman, the antlered animals traveled by rail to eastern parks and game reserves. At $85 to $100 a head, Rock turned a handsome profit. His largest sale of wild-game animals came in July 1895, when he shipped three carloads of elk to railroad magnate Austin Corbin’s 26,000-acre private hunting preserve in New Hampshire’s Sullivan County. Not every sale went through so smoothly. Two years earlier, he had shipped a carload of elk to New York City, but the would-be buyer backed out of the deal. Instead of bearing the cost of transporting the animals back to his corrals at Henry Lake, Rock donated the elk to a Brooklyn zoo.

Rock favored tracking in February and March when the snow was at its deepest and biting temperatures kept a crust on the snowpack that supported his 10-foot-long Norwegian skis. He used a team of Newfoundland-shepherd mixed-breed dogs to track elk and deer, both of which were easy to overtake, as their hooves would sink deep into the snow. An expert with a lasso, Rock would snare the animals and lash them to 8-foot sleds, which bore runners for easy gliding when pulled along in the snow by his dogs. Other times, Rock employed a more sedate tactic to collect the elk. He would place feed and hay within the 12-foot-high corrals on his ranch, and when the snow covered the highlands and forage became scarcer, the hungry animals would walk straight in. Over the years Rock sold more than 300 elk, which dealt with captivity far better than moose.

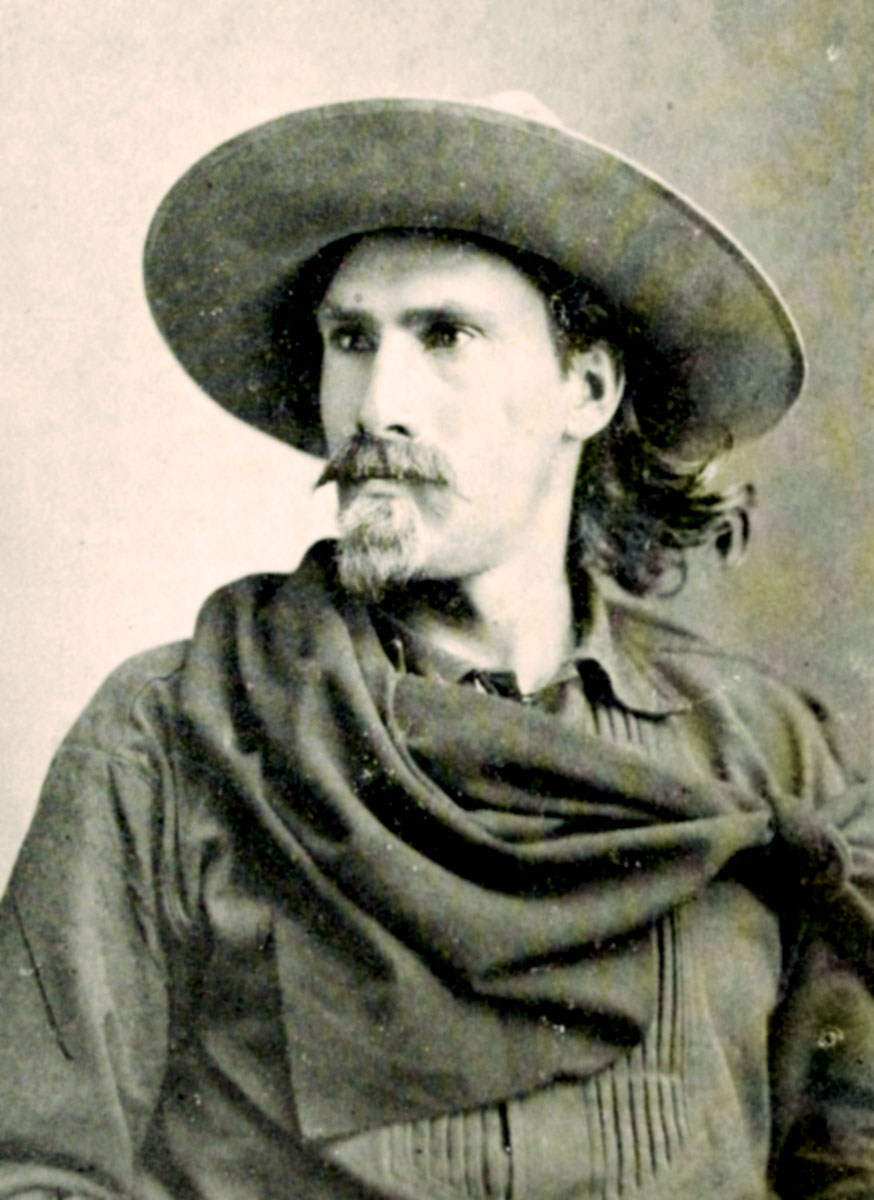

In 1901, Rock reportedly had 52 buffalo, three grizzly bears, 60 elk and large numbers of moose, deer and Rocky Mountain sheep and several black and brown bears at his game ranch. These animals were caught with a lasso when the snow was on the ground, secured and hauled to the ranch on sleds. There they had large quarters, but were securely confined. A few had been born in captivity. Rock had trained a moose to the harness, and it was a common sight to see him drive into Bozeman with his wife in their cart drawn by “Nellie Bly” (named after the pioneering female journalist). Nellie Bly proved most useful. Raised and trained to harness, Nellie replaced the dogs as the sled puller on a number of Rock’s winter treks to capture elk. The marvelous moose also pulled carts and raced horses. In an 1892 challenge, the enterprising Rock took Nellie to Twin Bridges, Montana, for a head-to-head contest with a champion trotter owned by Fred Connor. Once the wagers were laid down, the beasts lined up side by side, and the starter fired his pistol. The trotter didn’t go far. Glancing over at his strange competition, he bolted sideways. Nellie ran straight down the track and easily won.

Rock’s game ranch became a way station for tourists who entered Yellowstone National Park from the west, being situated 60 miles from Monida and 12 miles from Riverside, the edge of the park and right at the mouth of Targhee pass. The station was the end of the stage line from Monida and the camping ground for many tourists every season. Always the entrepreneur, Rock didn’t miss an opportunity to turn a profit. Stage passengers could tour his menagerie for free, but Rock sold them supplies, grub and a “touch of tanglefoot.” His reserve quickly gained a reputation, attracting wealthy businessmen, foreign visitors, governors and senators.

Looking for unusual animals to add to his reserve in the 1890s, Rock set his sights on mountain goats – surefooted, bearded denizens of the rocky heights in the Bitterroot Mountains. He stalked a tribe of goats through an entire winter and into the spring kidding season. After much effort, he managed to capture a couple of the kids. He raised them to maturity, then sold them in 1899 for $1,200 to Charles W. Dimick, who exhibited the pair to curious throngs at the Sportsman’s Show in Boston.

The Wide World Magazine interviewed Rock for an article. Some of the questions they asked were:

“Is the capture of a full-grown buffalo alive at very difficult matter?

“Exceedingly so,” was the prompt reply, “although there are animals that give more trouble. The instinct of the buffalo surpasses that of the shrewdest ranchman—because for ages he maintained himself where the cattle of the ranchmen are now dying.

“The buffalo is not difficult to trail, because he has certain habits which are always rigorously followed out. The herd rise at dawn and commence to graze. When filled, they start for the trail, led usually by an old cow, who gives the signal for starting by sounding a grunt not unlike that of a hog, only much louder. The remainder of the herd drop in behind, following exactly in her footprints until they reach the path which leads them to their drinking-place. This path never exceeds 12 inches in width. It is the same path along which the ancestors of these buffaloes have traveled for countless ages.

“Finding the trail of a bison is one thing, but getting him safely fastened to the sledge and headed for the ranch is something very different. The buffalo is quick to scent danger, but, owing to his bulk, he is not a very quick traveler. Mounted on a good horse the hunter can readily overtake his game. At close quarters, when enraged, the buffalo is a dangerous customer. He can deal a nasty cut with his short, wicked horns; and with head lowered as a ram he can land with terrific force, in regular catapult fashion, a blow from which neither man nor beast could ever recover.

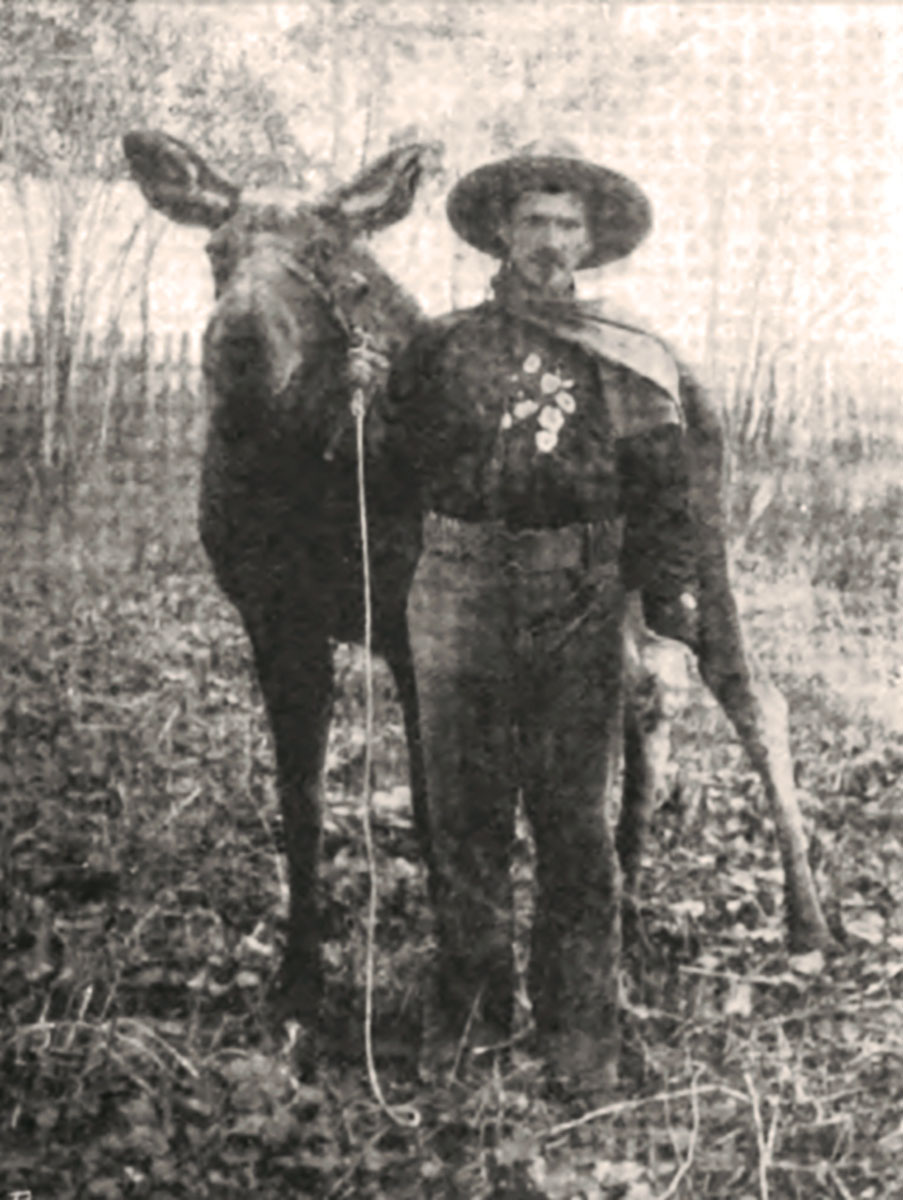

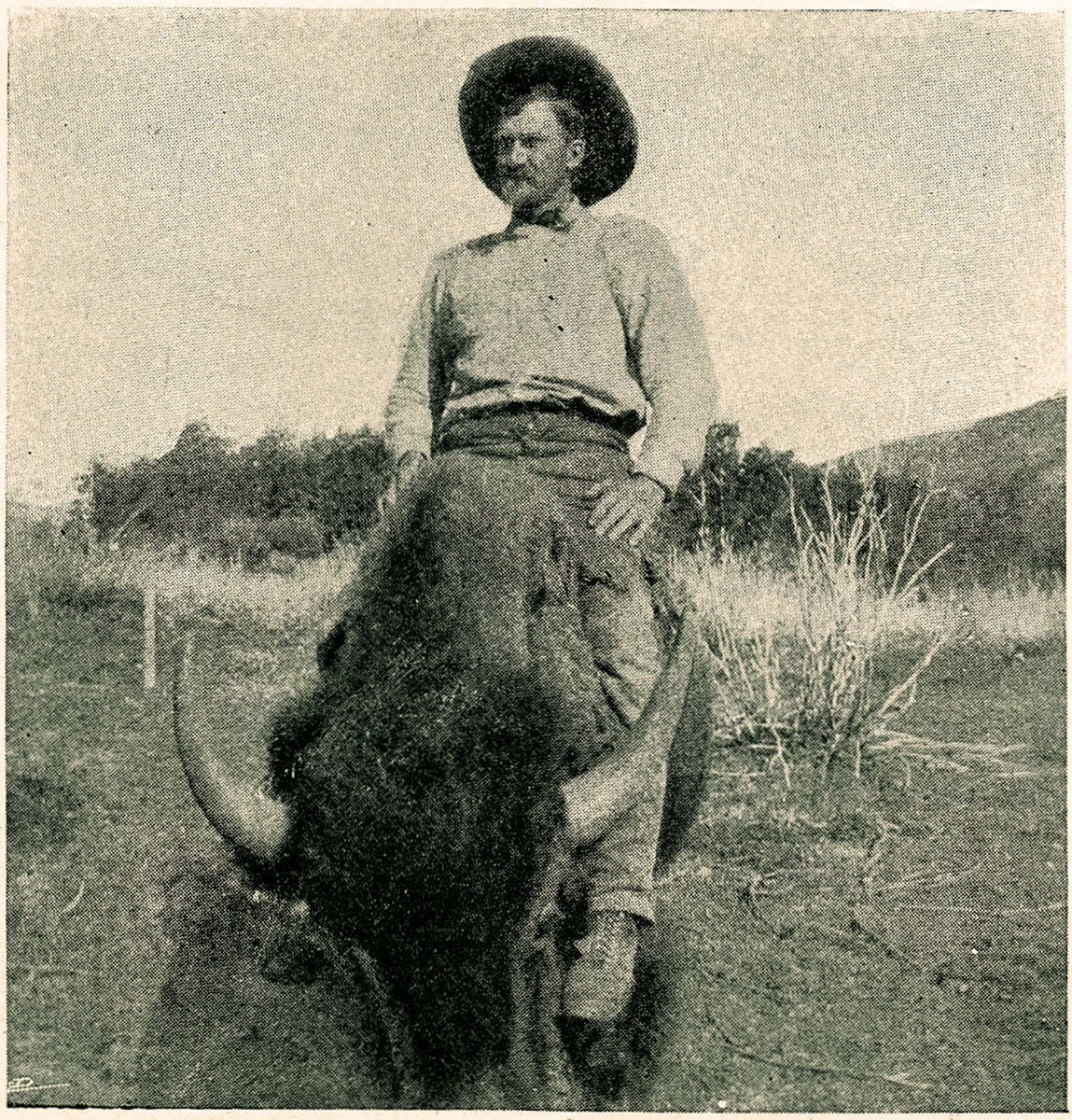

“Once lassoed and thrown on his back, however, he is easily managed and can be readily handled. In captivity, buffaloes usually prove very tractable, and can even be made companionable by kind treatment.” In proof of this statement, Mr. Rock proceeded to leap on the back of a huge fellow, which carried him around the yard several times, without manifesting the slightest uneasiness or resentment.

“The moose is also susceptible to the effects of good treatment, and I have one which I have trained to harness and frequently drive harnessed to a two-wheeled jumper. We have named her ‘Nelly Bly,’ and so tame has she become that she follows Mrs. Rock all over the ranch, eats from her hand, and in the morning even comes right up to the window to be fed. ‘Nelly Bly’ weighs thirteen hundred pounds and is very powerful. In my hunts after big game I frequently hitch her to my sledge instead of the dogs, and in this way, she has brought to the ranch many a large animal.

“Mr. Rock then pointed out his two mountain goats, the finest known specimens of the species in captivity; his sixty head of antlered, fleet-footed elk; three wicked~ looking grizzlies, including the one just captured, and as fine a bunch of black-tailed deer as was ever assembled together.

“Every one of these animals, excepting the younger ones which have been born on the ranch,” said Mr. Rock, “I have captured in their native haunts and dragged here on sledges over the snow.

“How long has it taken you to get this collection together?

“Over seven years,” he responded. “The best time to work is in the early winter. Then the great Western snows cover the ground often to a depth of two or three feet. Even the fleetest of animals cannot develop speed in this encumbrance. Their sharp hoofs stick heavily in the snow, whereas the trapper on his snow-shoes and with his light, quick dogs can travel at a considerable pace. When cornered in a heavy snow bank the game is handicapped seriously in its effort at self-defense. It flounders helplessly around in the snow, in a trice the lasso does its work, strong ropes fasten it to the sledge, and my collection of wild animals is augmented by one.

“Have you never been injured in any of these exciting battles?

“Oh, yes, several times, and I have had a hundred narrow squeaks, but have always managed to survive with my full complement of bones. Once a fierce bull buffalo knocked me down and so stunned me that, although I was fully conscious of my peril, I could not move or raise my hand to defend myself. Just as the maddened bison was about to finish the job by trampling me to pieces one of my brave dogs, barking furiously, leaped courageously at the mighty giant and succeeded in burying his sharp teeth in the buffalo’s soft, sensitive nose. Bellowing with pain the monster turned on the dog bent on annihilating him, but of course the agile dog leaped away. The instant’s delay was my salvation. Raising myself on my elbow I just managed to draw my revolver, and at close range shot the big fellow straight through the heart. Of course my collection lost an addition, but as I saved my life, I don’t suppose I should complain.

“Why did you settle down in this desolate, inaccessible spot?

“Principally in order to gain the privacy so essential to these wild animals. If located near a frequented place they would die of fright before they could become accustomed to the crowds and noise. I came here first with only a pack and a saddle horse, having ridden through the Rockies and other mountain ranges over one thousand miles from Galveston, in Texas. As soon as I saw this spot, I felt my ideal had been attained, pitched my tent, built a cabin, and as soon as I had everything comfortable brought my wife on. Then securing the necessary dogs and making suitable corrals to hold game, I waited for the December snows in order to make my initial venture in my new career. With hard work and almost indescribable exposure, I had succeeded by spring in securing seventy-five elk, three moose, ten deer, seven antelopes, and three mountain sheep.

“I have raised several buffaloes on the ranch and also one moose. The elk seem hardy and contented in their new environment, and breed as rapidly as when in their native state. Deer, moose, and antelope are of a restless, nervous nature, and do not multiply so readily as the elk. Since 1894 I have sold 350 head of elk alone to zoological gardens and public and private parks in the East, as well as many other varieties of animals.

“To be sure, there’s money in it,” concluded “Dick,” “but with me the getting of money is only an incidental motive, as it were. If it were not for my attachment to this glorious climate and my fondness for the independent, outdoor life I lead here I reckon I’d be back East. Same way with Mrs. Rock, Ohio suits her well enough to visit it once in a while; but for steady living give her Idaho every time and a ranch just about like this one, twenty miles from nowhere and as pretty as a picture.”

Rock’s wild animal enterprise ended abruptly the early morning of March 22, 1902. At the time of his death, Rock had collected one of the finest assortments of wild animals in the West. Among the buffaloes was the bull that Rock had named “Lindsay” and which he had raised from a calf. Lindsay was nine years old, and Rock frequently played with him in the corral. Rock had no fear of the animal.

On March 22, Rock was in the corral feeding Lindsay. For several years he had been taking rides on the back of his big pet, so he didn’t believe he had anything to fear. One of Rock’s friends, Kirby Garner, had warned him multiple times: “Dick, that buffalo will kill you someday. You had better be careful.”

On the fatal morning, Rock turned his back on Lindsay and the buffalo charged, pinning him against the corral rails with no means of escape. The disobedient pet’s spiked horn speared Rock and then he tossed him in the air, gored him and tossed him up several more times. Rock’s screams brought his wife and hired man, Bennie Tidcomb, to the corral. Even using a pitchfork, Tidcomb could not get Lindsay to let go of Rock. The bison gored its owner 29 times before a neighbor finally arrived and shot the beast. Rock, 55, lay trampled, his trademark sombrero crumpled in the dirt; all that was left of his clothing were the cuffs of his shirt and the socks on his feet. Lindsay was dead, and Rock soon followed his favorite buffalo. The other animals lived on in captivity, as U.S. Senator and copper magnate William Clark, of Montana, bought them and displayed them at his Columbia Gardens in Butte.

Sources:

“A Disinterested Plea for the Capture of Large Game,” Vic Smith, Recreation, Volume IX, No. 1, July 1898, New York, 1898, Page 61

Idaho’s Wild Animal Farm, The Courier-Journal, Louisville, Kentucky, August 12, 1900

A Wild Animal Farm, The Hancock Democrat, Greenfield, Indiana, February 21, 1901

Gored to Death, The Anaconda Standard, Anaconda, Montana, March 24, 1902, Page 1

Dick Rock Will Be Buried At Henry’s Lake To-Day, The Anaconda Standard, Anaconda, Montana, 25 March 1902, Page 1

Dick Rock, The Famous Guide and Scout, The Anaconda Standard, Anaconda, Montana, March 30,1902

Dick Rock, The Trapper, And His Odd Career, Anaconda Standard, Anaconda, Montana, 13 April 1902, Page 19

The Wide World Magazine, November 1900-April 1901

Dick Rock’s Zoo at Henry’s Lake, Henry Bannon, Forest and Stream, September, 1919, PP 460-461

Rocky Mountain Dick’ Kept Big-Game Animals on His Idaho Territory Ranch – from https://www.historynet.com/rocky-mountain-dick-kept-big-game-animals-idaho-territory-ranch.htm