A Tale of Two Hepburns

feature By: Tom Oppel | June, 18

As manufacturers did then and still do today, when there is something popular that can help sales, they create their own version of it. Thus, to capitalize on the Ballard .38-50’s popularity and hopefully enhance the sales of its latest No. 3 Model single shot rifle, Remington in 1883 created the .38-50 Remington cartridge. It was to be chambered in match versions of the new rifle, generally referred to as the “Hepburn.”

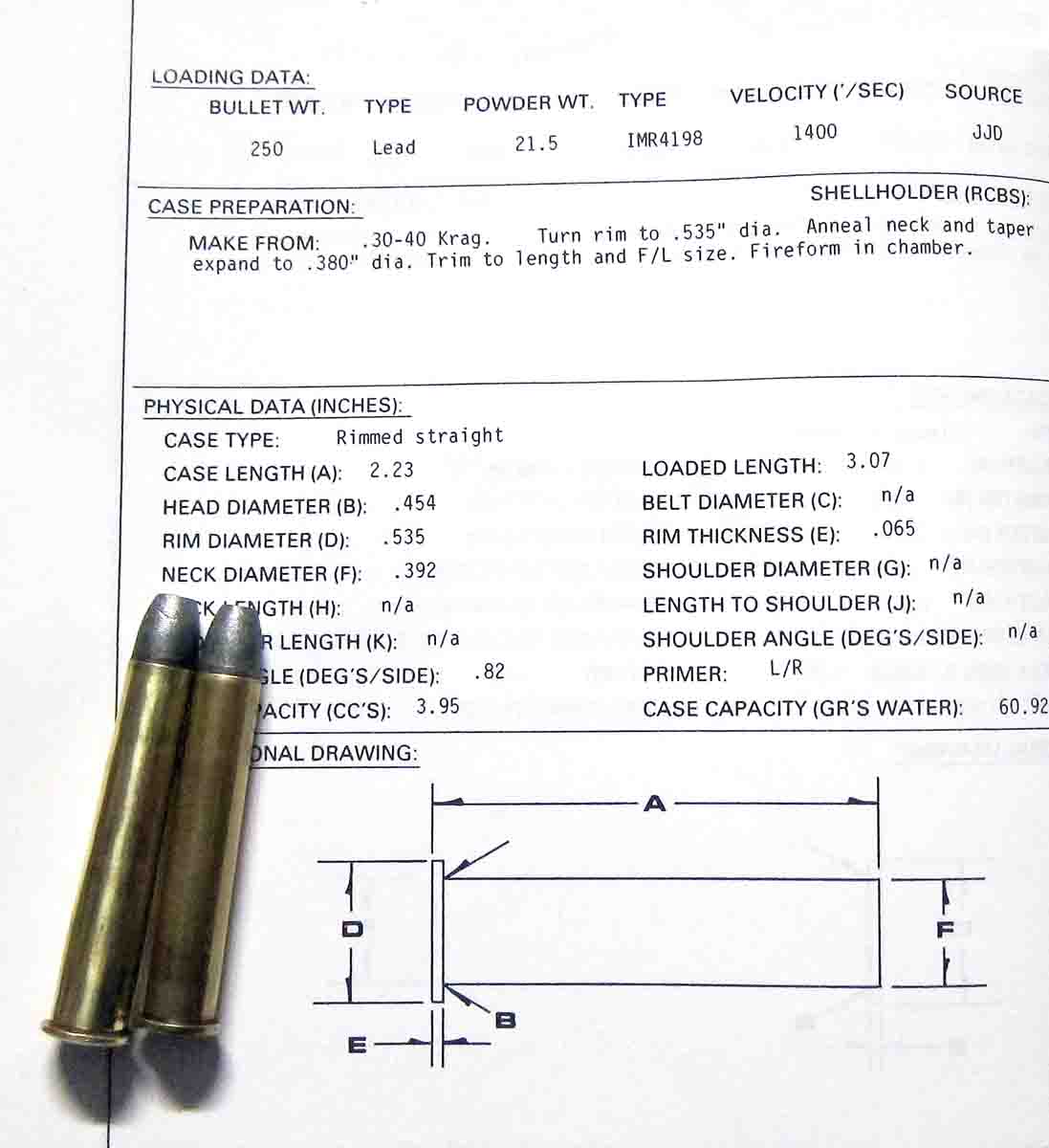

The three essential and irreplaceable references used for initial cartridge research were Ken Howell’s Designing and Forming Custom Cartridges, John Donnelly’s The Handloaders Manual of Cartridge Conversions and Cartridges of the World by Frank Barnes. In this particular case, Tom Rowe’s Hepburn book was an additional and very helpful reference. Howell’s book had no reference to the .38-50 Remington, although Donnelly’s and Barnes’ did. Rowe mentioned in the cartridge section of his book that brass can be formed from .30-40 Krag cases because both cases have the same head size. As many shooter’s probably know, the .303 British cartridge has practically the same head size as the .30-40, so the excess .303 brass I had was used for the initial loads; this exercise might prove easier than initially thought. Even if I did have a

It was decided at first to simply see if a loaded .303 cartridge would chamber in the rifle, which it did. The .38-50 case length is 2.223 inches according to Donnelly, and the .303 brass on hand measured 2.22 inches. I always have a good supply of .310-caliber cast bullets on hand. I loaded up two sample rounds of .303 British using a somewhat reduced charge of smokeless and the rest of the case was buffered with Dacron. These were tested in my backyard to see what would result. It was very encouraging, as the case was essentially fireformed with a minor crimp at the case mouth. This was easily straightened by belling slightly with a .375 Winchester expander die. Unfortunately, the powder charge was not recorded.

It is not necessary to go into all the details of how to load the .38-50 cartridge using the loading process that was developed. Suffice to say, it was accomplished with whatever dies I had in my inventory and some experimentation. If this “Rube Goldberg” method hadn’t worked, additional cash would have been needed to buy a die set from Buffalo Arms. The complete loading steps will not be listed here, only the exceptions to

Bell the case mouth with a .375 Winchester expander die, then start the wad in the case after it is charged with powder. Initially seat the bullets with a .375(2½) Nitro Express seating die is based on the .405 WCF, which essentially has the same base diameter as the .303 British and .30-40 Krag). Fully seat the bullet with a .40-70 BN seating die because it also slightly compresses the powder charge. Taper crimp the cartridge using a .32-40 seating die. That’s it – pretty easy and straightforward. A 50-grain powder charge of GOEX FFg, a .060-inch King poly wad, and a Sellior & Bellot primer was used.

The Rifles

I have two Remington Hepburns in .38-50 Remington; both rifles were discovered and purchased via the Internet.

Of interest is that the barrel is stamped “38” in front of the forearm, which is the normal place for Hepburn cartridge designation. According to Rowe, this is indicative of chambering for the .38-40 Remington cartridge. This rifle, however, is chambered for the .38-50, which is supposedly an exception. The

One of the things I like best about these old Sporting Hepburns is the steel buttplate. It is without a doubt the most intelligent of the late nineteenth-century sporting rifle buttplates and is unique unto itself. It is unlike the ubiquitous crescent buttplate found on almost all other makers of sporting rifles. These were essentially an industry standard with two spear-like points jabbing into your shoulder muscles – ouch! Though I have many of them, crescent-style buttplates are very uncomfortable to

For those who are wondering why the rear tang sight setup on this No. 3 looks like it does, here’s the scoop: My aging eyesight is barely able to use a barrel-mounted rear sight that came with the rifle, so I bought a Marbles tang peep sight. It was supposed to be for Remington vintage rifles, and indeed the spacing of the holes and sight angle did correspond to what this No. 3 was made for. These sights are very nicely made and are not cheap, both have built-in windage and elevation adjustments. It was no challenge to mount the sight on the No. 3 rifle. Ultimately, when the rifle was finally close to being sighted in, it was still shooting low and there was no elevation adjustment remaining, so I made the base as seen in the photos. It works even though it rather ruins the aesthetics of the piece.

The rifle was bore sighted as well as could be done and started to shoot at 50 yards. The target was setup with about a 3 square feet background of computer printer paper. I thought I could probably hit that target with a thrown rock at that distance.

The first few shots never appeared. I tried holding on the left side, the right side and high and low when finally a hit was noticed. It was evident why I was having so much trouble – the bullet was keyholing! Walking out to the target, I saw on the target board where my earlier shots had hit. I have to say I was pretty disappointed. This particular load used 5744 powder and Lyman’s excellent cast-bullet mould No. 375248 that is used with great success in my .38-55s. I assumed that the rifling twist was standard for this cartridge, which should and did stabilize loads using bullets of from 250 to 330 grains. There was no reason to believe otherwise. Checking my records, the groove diameter in the rifle’s bore was .377 inch at the breech end and .375 inch at the muzzle. However, it’s not a precision activity to measure the odd number of lands and grooves, five to be exact, in this rifle. The bullets had been sized to .375 inch. Measurements inside the case mouth from a few fired cases yielded a diameter of .378 inch, so the chamber is set up for bullets at least close to the diameter that was being used.

I thought possibly the loads might be pushing the bullet too fast, so the powder charge was reduced, but the keyholing persisted. Then a longer bullet was tried, an Ideal “Hudson” multi-diameter 330-grain bullet and sized it at .375 inch. Back at the range, these bullets keyholed as well. Next I tried to essentially duplicate a factory black powder load, again using Lyman No. 375248 and 50 grains of GOEX FFg – no good. Then some Hornady 225-grain jacketed bullets were tried – those keyholed, too! I thought, What was going on?

I decided to paper patch a few of the Hudson-style bullets to increase the diameter and they came out to .381 inch. A few of these were loaded but they would not chamber because of the increased neck diameter, which was clearly evident by the slightly bulging case neck. I decided to buy Lee mould No. 379-250, that should hopefully drop a bullet at or around .380 inch. A .380 lube/sizer die was bought to lube the Lee bullets. As cast, these dropped at .378 inch and were lubed “as is” with the .380 die, thus leaving them at .378 inch. These chambered and worked okay with a mild powder charge of 5744 powder. This load resulted in minimal keyholing and reasonable accuracy, but even though some progress was made, the rifle was still occasionally keyholing. Next, some black powder loads were tried with the Lee bullet and these worked somewhat, but there was still some keyholing. It was decided to go ahead with loads for this article, nevertheless.

I shot the Lee bullet loads first and encouragingly, the first four shots went into 2.4 inches at 100 meters. I was starting to get really happy about this. The next two did not even appear on the paper! The Hudson bullet loads on the other hand did not keyhole, but the eight cartridges I shot went into about seven inches with no apparent concentration, and some evidence of yawing. This rifle was an enigma so far and hugely disappointing. No, I did not want to sell it. I was determined to somehow get it to shoot! Using the larger diameter bullets seemed to be the right direction.

My second .38-50 is what Tom Rowe describes as a “Match Grade A” rifle. This designation is arrived at by the presence of the Swiss-style buttplate, upgraded wood, absence of a cheek piece and checkered forearm.

The rifle was purchased from Leroy Merz in Minnesota. Doing business with Mr. Merz has a unique benefit; if a gun is purchased from him he will give you full credit for it, less shipping costs, should you decide to trade it back to him on something with a higher price tag. In this case, an old British hammer shotgun had been purchased from him and was liquidating my British shotgun collection in favor of late nineteenth-century domestic single shots. Merz was good as his word and took the shotgun back for full credit and additional cash for the Hepburn.

Merz had the rifle listed as a “Match Grade B,” which contradicted Rowe’s description by not having the cheekpiece and checkered forearm. Rowe’s Hepburn book is the authority on the No. 3 rifle, bar none. Either way, I wanted this rifle. I am always leery of the bores on these old rifles but in this case, Merz said the bore was okay and should clean up nicely. It actually did, much to my great satisfaction.

This rifle has a 34-inch, full-octagonal barrel, double-set triggers, and weighs 9.75 pounds. The double-set triggers and the barrel length make the rifle a special order. The standard barrel length for the .38-50 Remington cartridge is 30 inches with the contour dimensions being close to Winchester’s No. 3 barrel weight. The full-octagonal 34-inch barrel on the Match Grade is similar to the Winchester No. 3 dimension as well. It was obviously set up for target shooting except for the sights; sporting rifle sights were on the rifle when I bought it.

One of the things noticed about this rifle as soon as the bore was cleaned up – the rifling depth was evidently more deeply cut than the other No. 3 rifle. Interesting! It also had five lands and grooves. The overall bore condition in the sporting rifle was somewhat better than in the Match Grade. In Rowe’s book, mention is made of possible paper patch rifling in early rifles, yet there is no definitive support for this theory. Paper patch rifling is supposedly shallower than grooved bullet rifling.

A short comment on the Remington double set triggers: According to Rowe, they are probably the worst of nearly all the makers of double set triggers during this period. It’s impossible to cock the hammer on the rifle without first setting the triggers. The let-off seems fine, however, I am not an experienced set trigger user. This is the first and only Remington set trigger rifle I have ever owned.

The cartridge designation on the underside of the barrel in front of the forearm is “38.2¼” which, according to Rowe, is the more definitive stamping for the .38-50 Remington cartridge.

Another batch of brass was formed for this rifle out of old .30-40 Krag cases using the same process as mentioned earlier. With the newly formed cases, I worked up some smokeless loads just to get the rifle sighted in. Also attached was a homemade tang sight with windage and elevation adjustments, along with a homemade globe-style front sight with removable inserts. The rifle was sighted in with no problems at all. No keyholing! It actually worked normally – imagine that! Then some additional smokeless loads were tried using different bullets. Not only was there an absence of keyholing, but the rifle shot all these loads rather well.

Now it was time to try some black powder test loads. Several were loaded, and all used the nominal charge of 50 grains of GOEX FFg, a King .060-inch poly wad, a Sellor & Bellot Large Rifle primer and several different cast bullets. The results were overwhelmingly good with all bullets. From these results, the best two bullets were selected: Lyman No. 375248 and Lee 379-250RF. I then made up black powder loads with bullets selected for uniformity in order to hopefully attain the best possible accuracy.

At this point, all range activity was stopped because of the extremely dry conditions in the summer of 2017. I did not get to the range for the .38-50 shooting session until late October, which coincided with the very beginning of our big-game season. Generally, the only thing I do during hunting season is hunt, or more precisely, I take the rifle for walks in the woods. I interrupted my hunting to do so.

The single range session for record was shot and the results are shown in the target photos. A total of 15 loads were used, seven with the Lee bullet and eight with the Lyman. As mentioned earlier, the Sporting rifle results were, except for four shots, very discouraging. The Grade A results turned out to be very good indeed, with a decided preference for the Lee 379-250 bullet. One seven-shot group went into 1.8 inches, four of those into .9 inch and three into .42 inch. The Lyman mould 375248 had a slightly larger, but still acceptable, eight-shot group of 3.5 inches, with six of those shots going into 1.8 inches. I am very happy with those results, especially with the Lee bullet.

These are the results so far with two examples of vintage Remington No. 3 rifles and the .38-50 cartridge – half were very good and half were disappointing. These days, Hepburns are quite desirable on the used rifle market. There were only around 10,000 made over an approximate 30-year period so they bring comparatively high prices. Should a shooter want to invest in one of these great single shot rifles, this research should be helpful.