The Wyoming Schuetzen Union’s “Center Shot”

Captain Bartlett - Gunman

column By: Jim Foral | December, 25

Publicly declaring a person – in print – to be a gunman, may or may not amount to an offensive accusation. It depends on the context. If the subject being branded were an exhibition shooter and a product of the nineteenth century American West, such a finger pointing would be a high compliment.

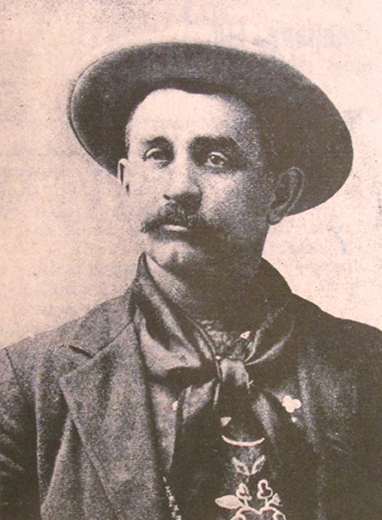

“Captain Bartlett, Gunman” was Bob Kane’s choice of titles for his profile of Captain George Bartlett after the gunman’s public demonstration in Milwaukee in 1909. Bartlett had led an active and adventuresome life in the West and he had the scars and the limp to prove it.

George Bartlett was not a native Westerner. He was born in New Haven, Connecticut, on August 25, 1858. His family moved to Sioux City, Iowa, in 1873. A year later, the teenager struck out on his own, landing in the close-by Yankton Agency in the southern Dakota Territory, where he worked at a trading post on the Sioux reservation. At 18 years of age, he took up with a prospecting party that was bound for the Black Hills where gold had recently been discovered. The party’s claim soon played out and George returned to Yankton. A year later he relocated to the Rapid City region where he became convinced that the prospector’s life was not his calling.

However, he did become aware that packing the mail was a paying proposition. In 1875, at the tender age of 17, he took the first U.S. mail sack into Deadwood, Dakota Territory. This was a route fraught with peril. He was once obliged to ride at night for three days to avoid Indian encounters. Caught out in a blizzard one night, he holed up in a hollow cottonwood stump for three days with only a jackrabbit for provisions.

Young George put in his time as a buffalo hunter to make ends meet on the plains. With evident remorse, he once admitted to having hunted for a living. History records that his buffalo rifle was a side-hammer Sharps in caliber 40-90 Sharps Bottleneck.

Anthropologist Warren Moorehead, who knew the man well, once wrote of him: “I suppose the number of deer, antelope, buffalo, elk, etc. he has killed would run into the thousands.” After his market hunter days were behind him, Bartlett cowboyed for a pair of huge Nebraska cattle companies. Young Bartlett had accumulated an impressive resume of adventuresome undertakings and occupations.

George came to know the country as well as any red man, and the U.S. Cavalry used him advantageously as a scout in that Sioux country. In 1879, he was engaged as a special deputy U.S. Marshall. In less than six months he had a regular government commission as a deputy, and he kept that position for 14 years. Deputy Marshall Bartlett spent his career among the Sioux. He was known to treat them fairly and kindly, and the Indian’s responded in kind. Their relationship was based on mutual fairness and respect. The lawman, over the years, became fluent in several Sioux dialects.

A life-altering episode occurred in Bartlett’s fifth year behind the badge. On Valentine’s Day of 1883, he was involved in an exchange of gunfire. His five-man posse had trailed the Exelby gang of horse thieves into the eastern Montana Territory settlement of Stoneville Station. In the surrounding hills the two sides came together within short rifle range of one another; it was seven men to six in favor of the bad guys. A couple of lawmen were shot and one killed, but the scoundrels that survived were apprehended.

Deputy Bartlett took a rifle bullet to his right kneecap. He was able to ride his horse as far as nearby Spearfish, where he was put into a wagon and rushed over the hills to Deadwood. There, Bartlett recorded, he received the “sympathetic ministrations” from no less a Western personality than Calamity Jane. She did her best to patch him up and later prevented the doctors from removing his leg. The lasting effect for Bartlett was a lifelong limp together with some lingering pain and some limited mobility. “It beats a wooden leg” he would later rationalize. If there was an upside, his limp was a trademark and professional identity. “Wounded Knee” became his byname. To the Indians he became well known as “Huste” – Sioux for “Wounded Knee”.

With Deputy Marshall Bartlett’s mobility compromised, and no longer a full-strength lawman, he took a position running the trading post on Wounded Knee Creek in the Pine Ridge District of the Sioux reservation. Some said that the stream was named in the white man’s honor. Others insisted that it had been known by that name for many years beforehand. It was from the vantage of the front door of his store that Bartlett eye witnessed the proceedings of a battle on December 29, 1890, when U.S. Army troops, including a contingent of Seventh Calvary Troops, still sore about the Little Big Horn, had arrived by special train in anticipation of an opportunity. Nearly 300 Indian men, women, and children died in the lopsided victory.

Bartlett remained on the scene for several days afterwards. He spearheaded the task of burying the heaps of dead and frozen Lakota, and generally made himself useful.

After the Wounded Knee events, opportunities on the reservation, or with Indians generally, had played out altogether. Bartlett resigned the Deputy Marshal position he’d had for 14 years and relocated himself to the horse ranch he’d acquired as a side venture. His place sat just across the Nebraska border near the little town of Gordon. When the ranch played out, Bartlett drifted East with a theatrical company which put on the Great Train Robbery stage melodrama. He was also engaged to give a shooting exhibition and wrangle “eight genuine Cheyenne Indians” which gave “color to the plan”.

In 1893, opportunity knocked for the former lawman that put his fluency with the Sioux languages to a good and paying use. A promoter had hired him to shepherd a band of Lakota Sioux to the 1893 Worlds Fair/Columbian Exposition in Chicago. While there, he and his wards signed on with a minor Wild West Show. The Indians were the attraction, but Bartlett himself put on a shooting exhibition. He discovered that he had an innate flair for the craft, and that it came naturally for him to master it, as a self-taught student. He practiced diligently and became adept at the various stunts associated with the trade.

One opportunity followed another. On the road with Adam Forepaugh’s Circus in 1896, Captain Bartlett added a Deadwood stagecoach to his act, and it became a popular attraction. By then, he had embraced the fancy shooter’s tradition of using the honorary title of Captain, in much the same way auctioneers have all promoted themselves to colonel.

The Eastern audiences had an appetite for hair-raising adventures, and grilled Capt. Bartlett for tales involving gunplay and blood spilling. The people were anxious to know about firsthand experiences of lawmen in the American West. After his performances, Captain Bartlett accommodated them with a limited “question and answer” session that was prone to go into overtime.

In the same way, Captain Bartlett would weigh in and set straight the sporting journals and papers that in their ignorance, would often take liberties regarding the honest, imaginary West as he’d experienced it. When the need arose, he would also defend the genuine, bona fide and free red man he’d lived alongside and came to regard highly.

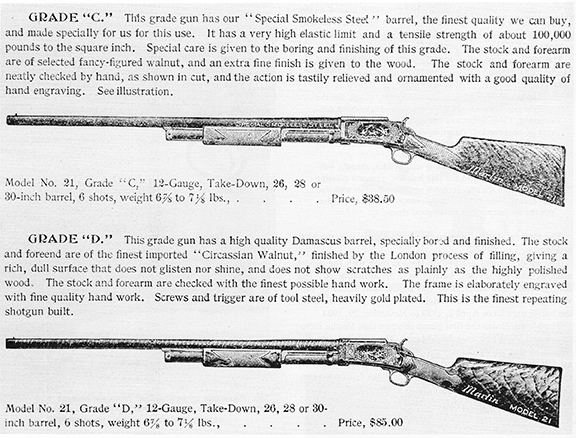

In early March of 1898, Harry Marlin notified the press that George Bartlett had accepted a public relations position with the Marlin Firearms Company. The new hire was to be the central figure at the Marlin exhibit at the two weeklong New England Sportsman’s Show held in Boston that same month. Bartlett manned the sizeable Marlin booth at the important affair that took up six acres of floor space. He made himself available to meet the public, mingle, shake hands, and answer the steady barrage of questions. He was to generally present himself publicly as a cordial Marlin personality. Marlin trusted him to put its best foot forward, and it wasn’t in any sense a gamble.

Bartlett put in a lot of time at the important Eastern trap shoots that year, and was very often seen in the company of Harry Marlin with both men shooting their lavishly engraved Marlin pump shotguns. Some exhibition shooting with the Marlin lever action rimfire rifles was done at the edge of tournament grounds. Marlin kept Bartlett busy.

In April of 1900, Capt. Bartlett won first money at a New Haven Gun Club important main event shoot. Mentioned in this same Forest and Stream blurb was the presence of Miss May Clinton, she of the female trick-shooting duo of Cook and Clinton. May had just had her first go at the traps. At the important trap event, the Trenton, New Jersey, “Interstate”, Capt. Bartlett was in attendance, as was Harry Marlin. Coincidently or not, Miss May Clinton was also present. Sparks will – and did, fly. In July of 1900, Capt. Bartlett was still with Marlin – as was May Clinton. In late November of that year, it was quietly announced that, “Miss May Clinton (Mrs. George E. Bartlett), together with her shooting partner Miss Pauline Cook, both known in the theatrical profession as “Misses Cook and Clinton, Lady sharpshooters, are to go with Capt. Bartlett to Europe to give shooting exhibitions.” The ambitious plan was to tour and perform in Europe from one to several years.

For 1901, they were set to open in Copenhagen in March, then to Germany, Russia, England and France where they had many dates already booked. Better-laid plans than this one of Capt. Bartlett’s have also gone awry.

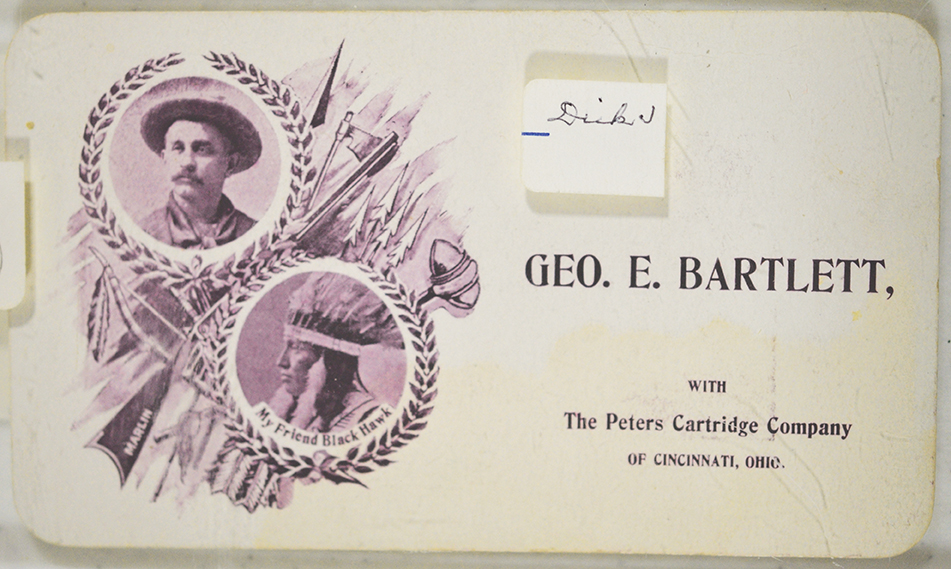

The various sporting papers sporadically kept its readers apprised of the comings and goings of the more public personalities in the industry. Particularly newsworthy was the July 6, 1901, leaking that George Edward Bartlett was “now a resident of Cincinnati and had recently attended a shoot representing Kings Smokeless Powder Mills and Peters Cartridge company.” It was thought that Warren King Moorhead, an anthropologist, and Mr. Bartlett had formed an association while in South Dakota at the Pine Ridge District in 1890. Mr. Moorhead was then on assignment from a publishing concern to study and record the Ghost Dance phenomenon from the perspective of an anthropologist. Moorhead and Bartlett, who were among a very small handful of white civilians on the scene, had been sketched together for a magazine illustration in the same Wounded Knee office. They would have spent considerable time together.

Mr. Moorhead belonged to the King family, principals in the King Powder Mills. The Peters Cartridge Company was separated from the King Mills by Ohio’s Little Miami River but connected by family, convoluted ownership, and an interlocking management. Bartlett was recruited by Peters just when he needed to find work.

Understandably, the active exhibition shooter of Bartlett’s era had a finite number of tricks that could safely be performed before an outdoor audience. Truth be told, the whole group of those in the game all performed the same limited stunts with varying degrees of proficiency and with minor variation. Skill and showmanship always varied in degree. Bartlett’s show followed the formula.

When Mr. Bartlett performed in Milwaukee, in 1908, Outers Book columnist Bob Kane was on hand to record it for posterity in a feature article in his magazine. It was the custom of his fellow trick shooter to begin with an interesting and instructive talk on guns and ammunition generally before the actual shooting. He started his Milwaukee show using a new-to-the-market Remington Autoloading rifle in 30 Remington in chambering. He then proceeded to reduce to dust airborne chunks of brick as fast as a practiced assistant could pitch them into the air. The bigger remnants were then tossed two at a time and each piece receiving the same pulverizing.

Next, oranges, apples, and potatoes wrapped in several layers of colored tissue paper were heaved skyward. Each was struck with a speedy .30 caliber bullet and was vaporized for a dramatic and colorful effect, and an immense flutter of paper smithereens spinning to the ground. One by one, a good quantity of dollar-sized discs punched from quarter-inch boiler plate, were hurled next. Each was neatly holed with the .30 caliber self-loader. This trick was universally a trick shooters staple. Bartlett had mastered it to a nicety.

With a Stevens 32-20 rifle and a mirror and his back to the targets, he faultlessly picked off walnut-sized targets. Picking up a rimfire autoloader, and with two assistants heaving nuts, marbles, and like-sized objects, he sniped each without a miss. More aerial shooting with the centerfire Remington autoloader then got its turn. Half dollar-sized metal discs were tossed by a stout assistant. Bartlett’s .30 caliber bullet intercepted each in its descent and each ricocheted into the lower stratosphere.

Captain Bartlett ended his act with a Remington autoloading shotgun. Hitting the tossed tomato can looked easy, as was each can in a succession of cans. The last can thrown was with the demonstrator shouldering a gun with a barrel length extended magazine. Each connecting shot drove the airborne can higher than the last, and when the gun was empty the can was a speck in the clouds. This shooting that Mr. Kane and his fellow citizens of Milwaukee witnessed, was also the first such shooting to be recorded in motion pictures.

It was thought that Mr. Bartlett’s recruitment and association with Peters, the Circle P brand, was orchestrated by Mr. Moorhead. In any event, everyone involved seemed content with the arrangement.

Professional shooter and polished showman, George E. Bartlett, was with the firm as its demonstrator at least until mid-1906, when he was still shooting a well-worn slide-action shotgun, his standby auto-loading 30 Remington, and his nickeled and engraved Marlin lever action rimfires. His was never a household name, but he still ranks with the best of his kind. Along the way, he lured the Nebraska trick-shooting standout Andrew H. Hardy to perform professionally for Peters for a good string of years and who managed to outshine Mr. Bartlett.

In the spring of 1910, Bartlett was still representing Peters in some capacity at their San Francisco offices. On April 19, 1911, after an accomplished and adventurous life, 52-year-old George Bartlett died at his home in Los Angeles. He left behind a sizeable collection of important Indian artifacts, and several guns he acquired from the Stoneville, Montana shootout, from the bodies of the bad guys who “no longer had a need for them.”