The Express Rifle

feature By: Rick Weber | December, 25

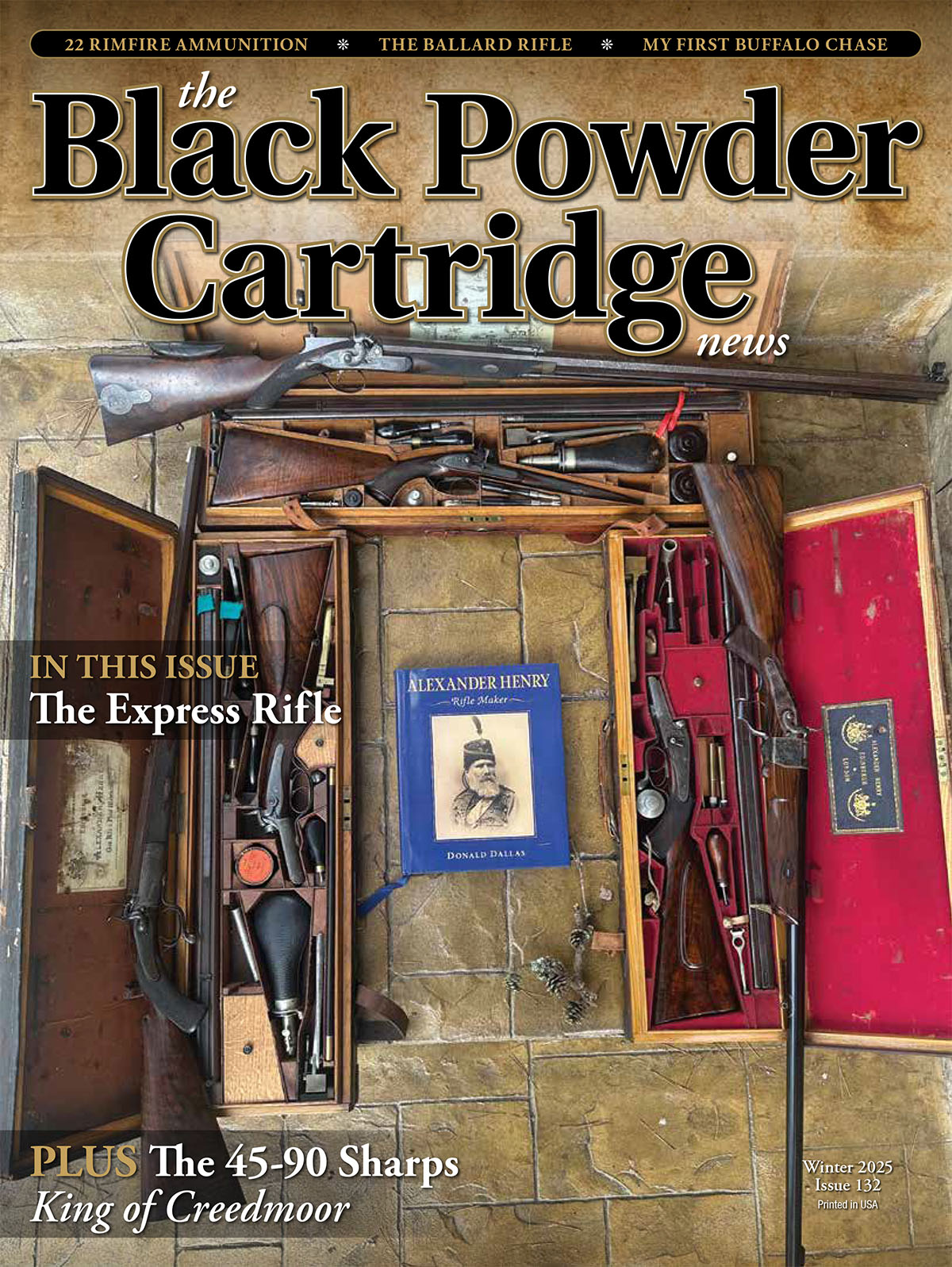

Henry’s prolific career as a gun designer, shooter, and builder allowed him to utilize fine departmentalized cases with all the accoutrements that accompanied his best works. Everything a sporting man (or British officer) would need was included when traveling abroad to the lands of the British empire; if only this particular case could talk. It is made of oak and is covered in leather with two belted straps to assure it does not open during transport. Oak – solid, heavy and certainly chosen for those qualities. The interior lining of this case is thin pig/goat skin with a “paste” grain, so I’m told. I do know Marvin Huey cannot duplicate this material, as I need some for another Alexander Henry case. The stock was made of walnut and has a few small knots (that fact did not seem to bother the makers of the time) but the wood grain goes through the wrist as it should; no straight-grain slab sawing here. The wood to metal fit is as to be expected with a “Best” piece. The Damascus is still showing the triple-twist pattern of the tapered and slightly swamped barrels. Rosewood “Extra Use” rods are tucked under the barrels in the case. The barrels on this Express Rifle are 32 inches and are the longest I’ve seen on a double rifle of this era; most are 28-30 inches. I’m not sure about any extra bullet velocity because of the length, as I really do not care – I want accuracy. But, those long barrels do look sexy!

Alex Henry and his shop did all the legwork in regulating the barrels and he was kind enough to include such information inscribed on labels within the cased set. The charge is listed as “110 grains of Curtis & Harvey No. 6, with wooden plug, papered and wad attached.” The cavity base for a wooden plug is to assist with engaging the rifling (although I find soft lead to do the same). “Paper-patched and with a wad attached.” Who attaches their wad this way today? I do it – because Mr. Henry did it!