One More Shot with Old Powder

feature By: Mike Nesbitt | December, 25

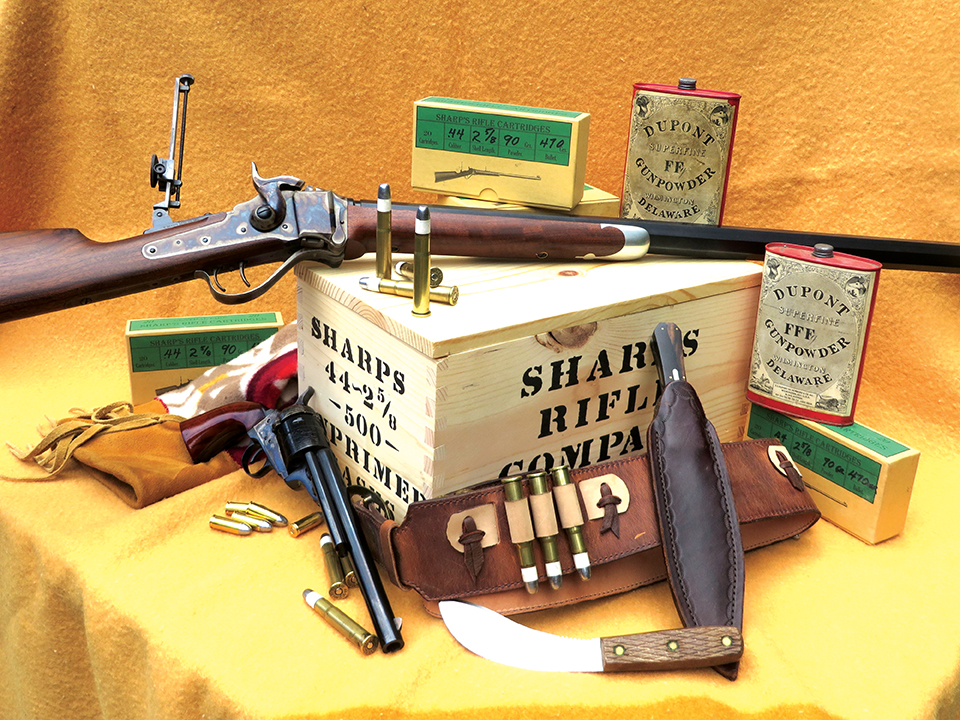

Getting started to load one round with the old powder charge taken from the 44-90 Sharps cartridge that was featured in What’s Inside an Old 44-90, was a bit different from how things went when the same thing was done previously with the powder from the 44-77. For one thing, the 44-90 used a .441 diameter bullet and I had no previous experience with 44 Sharps bullets that were that large. However, I was determined to find out, so the process began with finding some .441 bullets.

There was really no problem because Buffalo Arms Company stocks swaged bullets of this diameter for paper patching. BACO lists a number of weights available for these bullets but the heaviest is 500 grains. Even though the original cartridge’s bullet weighs 520 grains, the 500-grain bullets would be close enough in trying to duplicate the original loading. BACO does currently list a 530-grain bullet, as well as 550-grain bullets with a .441 diameter, although I’m not sure if those were in stock at the time. The order for one box of 50 bullets was sent in and they were received shortly thereafter.

Patching the bullets was the next step. These rather large bullets for the 44 Sharps needed patches cut with a 45-caliber template, which worked quite well. The bullets were given their usual two wraps with nine-pound paper, which was also ordered from Buffalo Arms. These .441 diameter bullets are not tapered, which made wrapping the wet patches all the easier and soon I had a small batch of bullets, dried and ready to load.

One more comparison was made between the old original 520-grain bullet and the new 500-grain bullets and that was to measure the diameter of the patched bullets. The old original bullet measured a full .450 just ahead of the case. One of the new bare .441 diameter swaged bullets was measured after patching with the double wrap of nine-pound paper, and it also measured .450 in total diameter.

Before doing the loading to check the velocity and bullet impact elevation with the old powder, I wanted to give these “new-to-me” bullets a try. I only loaded five of them. The five un-sized Jamison cases were primed with Winchester Large Pistol primers. Swiss 1½Fg was selected for use, 90.0 grains of it. The powder was compressed under a milk carton wad and pushed down to the bottom of the case neck. Then a wad of lube (BPC lube from C. Sharps Arms) was added to keep the fouling soft. Finally, the bullets were twisted into the cases and seated with just my fingertips as trying to use a seating die with paper-patched bullets might result in tearing the paper.

Those bullets needed some special attention while getting them into the cases just because they were on the large side. The cartridges also needed some special attention when getting them into the rifle’s chamber. They couldn’t be completely chambered without a chambering cam. The cam was needed to push the cartridge into the chamber all the way, which would also have the bullets entering the leade of the rifling. That could be felt while using the chambering cam and I must point out, the only safe way to unload the rifle with the cartridges chambered this way was to shoot it. One could use a ramrod to push the cartridges out, but that is not recommended, and it is an unsafe procedure at best. Shooting the bullets was the best way of getting them out of the barrel, and let me say, these bullets certainly did shoot. My first target was a standard bullseye posted at 100 yards. Only one bullet strayed out of the 10-ring and I assume that was my fault. The group delighted me and the target could be scored as a 48-2X.

Before loading the cartridges for a comparison with the load that used the old powder from the dismantled 44-90 cartridge, powder for these loads needed to be considered. Selecting a new powder, as close as possible to the old powder, would be wise. However, the only way to make such a comparison with the powder I had available was to visually see which type might be the most similar. This logic is flawed because it can’t include powder density or any possible chemical differences. Powder density might be determined when the cartridges were loaded, but could only show if the old powder was more or less dense than the new powder. The chemical make-up of the old powder couldn’t really be considered, especially when I had no real idea of who had made the old powder.

So, for what it was worth, the old powder was visually compared with Swiss 1½Fg and Olde Eynsford 1½Fg powders. The grain size was very similar to both of those new powders and the Olde Eynsford was selected for the new loads primarily because the darker color of the Olde Eynsford was a closer match to the old powder.

With that selection made, the loading of the cartridges began. Again, fired, but un-sized Jamison cases were primed with the Winchester Large Pistol primers. Then 90 grains of the Olde Eynsford powder was measured, using a powder trickler to get the individual powder charges the same for each of the loads. After pouring that amount of powder into the case through a funnel, it came about a quarter-inch from the top of the case neck. A card wad, punched from a milk carton, was put over the powder and then powder and wad were compressed so the wad was resting just above the bottom of the neck. Following that was an 1⁄8-inch or more of lube and the load was then completed by carefully seating the bullets with fingertips, making sure the bullets were down as far as they could be pushed by hand.

As noted, in the story about What’s Inside an Old 44-90, the powder in that old load weighed just a bit under 90 grains; 88.3 grains were in the load I had measured earlier. So, (pardon me if you disagree with my judgment), I treated the old powder just like the new powder and trickled just enough of the new Olde Eynsford 1½Fg powder into it, in order to bring the powder charge up to 90 even grains. Yes, we can agree that doing so contaminated the old powder charge. Perhaps a more accurate comparison would be made if I had weighed the original powder charge again and copied that weight with the new powder. For that idea, I can only respond with “maybe next time”. For this test, I did add some new powder to the old, to give it a full charge and the added powder was certainly less than two percent of the total powder charge.

The cartridge with the old powder had its primer painted black for identification and the only thing left to do was to find a decent day to run the loads over a chronograph and see if they’d group together. Those loaded cartridges certainly looked impressive and ready to shoot with their overall lengths of 35⁄8 inches.

However, before getting the chance to start the shooting, the thought occurred to me that at least another six rounds should be loaded using the same .441 diameter paper-patched bullets but using 90 grains of Swiss 1½Fg powder. Again, each powder charge was individually weighed to be sure that consistent powder charges were used. That would be done just to satisfy my curiosity about any differences in the performance of the Swiss and Olde Eynsford powders, as well as adding to this story. So those six rounds were loaded and the primers on those particular loads were painted blue just for positive identification.

One reason to have all of the loads prepared was so the shooting and chronograph testing could all be done on the same day, with only one outside temperature and humidity reading to consider. In that way, any differences in the velocities of those loads would be from differences in the powders and not some other influencing factor.

Of course, the proof would be in the shooting. In addition to getting a velocity with the load that used the powder from the original load, we’d also get to see a comparison between the 90 grains of Olde Eynsford 1½Fg powder and the 90 grains of Swiss 1½Fg. The only expectation I had was those velocities might be pretty much the same.

For the shooting, I called on the assistance of my good friend, Allen Cunniff. Allen is usually a much better shot than I am, mainly because his eyes are 10 years younger. So, in order to give those loads their best chance, I asked him to do the shooting. I’m sure Allen gave it his best effort but, for one reason or another, the groups were not as tight as what I had hoped. That’s how things go, and for this report there was no chance of doing it all over again.

In addition to reporting on the shot taken with the old powder, please allow me to make certain comments on the loads fired with new powders; these shots were necessary in order to compare the old and new powders.

The first loads to be tried were the ones using 90 grains of Olde Eynsford 1½Fg under the 500-grain paper patched bullets. Those gave a velocity average of 1,320 feet per second and I must add, they had the poorest group. Why that was, I can’t say. Perhaps being fired first, in a non-fouled barrel, could be a clue.

Next, the loads with 90 grains of Swiss 1½Fg were used and those turned in a velocity average of 1,383 feet per second, with a high velocity of 1,407 fps. The Swiss loads grouped somewhat like the ones I fired previously. Allen was using my sight settings and his shots went a bit high and to the right but the group was, at the least, acceptable. One detail about those shots with the Swiss powder was that there was some fouling ahead of the chamber, which suggests that the powder was too hot for the loading. This was determined when we wiped the bore between shots and it prompts me to try these bullets again with a charge of Swiss 1Fg powder.

Our final shot was the load that used the charge of old powder, taken from the old 44-90 cartridge. That single shot had a velocity of 1,342 feet per second, which put it between the Olde Eynsford and the Swiss. On the target with the group fired with the Swiss loads, the one shot fired with the old powder hit in the white, the lower of those two shots just outside of the black. In fact, the shot with that old powder simply seemed to fit right in.

Once again, shooting this individual shot with the old powder was a success. I wish I had more of it and I also wish some real information about it could be stated such as, who had made the powder, when, and what granulation it was. My estimates about that powder are merely guesses. However, I certainly enjoyed trying to take this look back into yesteryear and if I get the opportunity to do it again – perhaps with another caliber – I’ll jump at the chance.