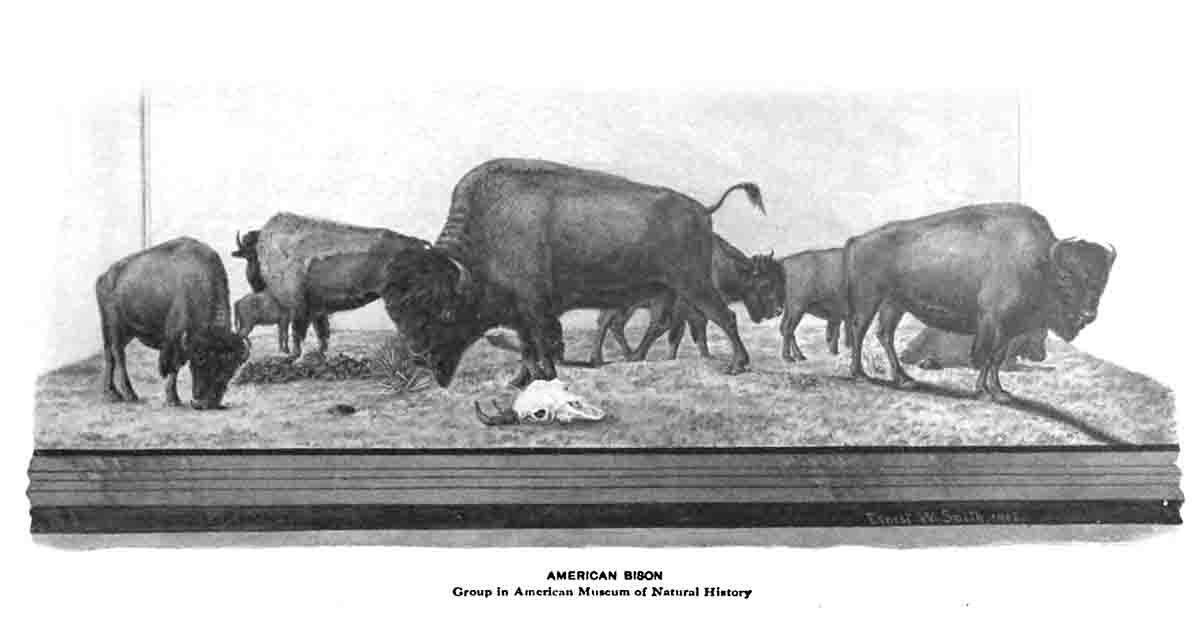

On the Buffalo Range

With Joel Asaph Allen - Specimen Collector

feature By: Leo Remiger | December, 18

Beginning in April 1871, Joel Asaph Allen embarked on a nine-month trip to collect specimens for the Museum of Comparative Zoology. He took with him two assistants; Richard Bliss, a fellow student at the Agassiz

General specimen collections were made at intervals from the Missouri River to Great Salt Lake, Utah. As western Kansas was then subject to raids by hostiles, Allen was provided with letters of introduction from Major General Pope, commander of the Department of the Missouri, to the commandants of the various military posts near their proposed route through Kansas and Wyoming. The letters also requested the various commandants provide escorts and transportation as required. Fort Hays was selected as the central base from which to hunt buffalo. Vacant officers’ quarters were assigned to the party for their use during the six weeks they spent at that location.

The Allen party had spent the first 10 days of May at Leavenworth and then traveled to Topeka where they were engaged for two weeks collecting specimens of various birds, fish, reptiles and insects. The Allen party arrived at Fort Hays on May 26.

They were still waiting for the necessary military escort with an indefinite return date that was out guarding government supply trains when, on July 3, a chance encounter introduced them to Charles Clarkson, a professional buffalo hunter who for several years had hunted buffalo in winter for meat to ship to eastern markets:

This intelligent, enterprising and level-headed New Englander, who lived in a dugout on the outskirts of the military reservation, who owned a good pair of mules and a wagon, and was familiar with the ways of the Sioux Indians, assured us it would be quite safe to go on a buffalo hunt without the encumbrance of a military escort.

As Clarkson was willing to act as scout and hunter to furnish the Allen party with the necessary transportation in exchange for a reasonable consideration, the Allen party decided to trust his judgment and left Fort Hays on a buffalo hunt on June 21.

Allen describes the trip as follows:

We left Fort Hays on our buffalo hunt June 21, returning four days later with a wagon load of buffalo skeletons and skulls, besides leaving on the open prairie five skeletons we had prepared that we were unable to bring with us for lack of room. As we still needed an old cow, and had secured no calves, Clarkson and I returned to the buffalo range the next day, and at the end of another four days had completed our desiderata, having not only secured a fine old cow skeleton and a number of young calves, but had also retrieved the skeletons left on our former trip, which, however, we found had been somewhat damaged by coyotes. In all our spoils numbered 14 complete skeletons and several additional skulls, representing both sexes and various ages, from yearlings to old bulls and cows; also, the skins as well as skeletons of five young calves. The time thus occupied was eight days, involving about thirty-six hours of travel. We saved no skins, except those of the calves, as at this season the old coat had been shed (except of course on the shoulders and head) and the new coat was so short that it barely concealed the skin.

The experience was one long to be remembered, as we took no camp outfit but our blankets, a little flour and canned fruits, depending naturally upon buffalo meat for our main subsistence, buffalo chips supplying us with fuel. Our blankets were our only shelter at night, and our wagon was the only available screen from the hot midday sun, under the shade of which we crept to eat our dinner [Journal entires indicated 105 degrees in the shade on one occasion and usually over 100 degrees at midday]. We saw no Indians, but the landscape was everywhere dotted with small bands of buffalos; which were so numerous on one occasion that they darkened the plains to the west of us as far as the eye could reach. They were given no peace by the skin hunters, several parties of whom we met on the range. The skins then sold for two dollars each at the nearest railroad station. Once a small band of buffalo, stampeded by these hunters, sent us to our wagon for safety, the herd passing on both sides of us almost within arm’s reach.

After the Allen party returned from this buffalo hunt, they packed their collections that they had accumulated at Fort Hays and shipped them East; part to Rochester for preparation and part direct to the museum at Cambridge. On July 3, they took the train for Denver. They spent two days at Denver, and outfitted for a wagon trip into the mountains. They left for South Park on the afternoon of July 6, camping the first night at Turkey Creek, just behind the first range of foothills.

The Allen party returned from South Park by way of Pike’s Peak, Manitou Springs, and the Garden of the Gods. They remained in this vicinity collecting for nearly a week and then traveled along the outer base of the foothills northward to Denver arriving there on August 18. They then spent 10 days in the vicinity of Cheyenne before moving to Ogden, Utah. They remained in Utah for seven weeks collecting specimens of avocets, stilts, phalaropes, other marsh and shore birds as well as ducks, terns, gulls, varieties of fish, mollusks and crayfish. On October 9, the party took a train east to Green River and remained until October 17 securing fossil fishes from the Green River shales. High winds, ice and snow made collecting specimens difficult.

From Green River, they went to Fort Fred Steele and arrived there on October 18. Their idea had been to hunt the mountains for big game. They soon decided the plan was impractical owing primarily to the expense

The Allen party went into camp at Percy and remained there from October 20 until December 18. Their workshop was a log cabin that had previously been a saloon.

For two months they worked six days a week, preparing the big game delivered to them at frequent intervals by Ferris and Hunt. Allen writes:

About one day in seven we devoted to hunting, and added this to our spoils several antelopes and coyotes, jack-rabbits and cotton tails, besides many birds, including a large series of sage grouse, then so abundant that Bennett and I, on one occasion, shot thirty in an hour – all we could carry to camp, and could have killed as many more the next hour had we needed them. As no hay or similar material could be obtained at Percy, we had to substitute dry grass for filling the skins of the mammals, and to obtain this we had to tramp to a moist ravine a mile and a half away, cut it with our hunting knives and carry it home on our backs. A journey of a hundred miles by rail to Laramie was necessary to obtain material for packing cases, namely, discarded dry-goods boxes, which we dismantled and shipped as freight to Percy and remade to suit our needs. Roughing out skeletons and preparing skins of deer, elk, mountain sheep and antelope occupied our time and kept us confined to our laboratory for the greater part of these eight weeks, but our enthusiasm was well sustained by the results, and now and then a day’s tramp through the sage brush and snow relieved the monotony.

Our shipment of 17 large cases from Percy included skins and skeletons of eight elk, 12 black-tailed deer, one white-tailed deer, 25 prong-horned antelopes, and 11 bighorn sheep; also 35 skulls of antelope and a fine series of the skulls of elk and black-tailed deer, besides small game (coyotes, foxes, porcupines, beaver, rabbits, etc.) and birds. It nearly filled a freight car, and was shipped on December 17, but as will be explained later, did not reach its destination for several months.”

On December 19, the Allen party boarded an eastbound train for Omaha, already 12 hours late, when it reached Percy. A mile and a half east of Percy they ran into a snow bank and the train was partly derailed and delayed for another two hours. Between Carbon and Medicine Bow they were again stalled in snow for 22 hours where they had to await the arrival of a wrecking train and two engines to replace their disabled ones. They got their first square meal in two days at Sidney. They struck additional heavy snowstorms at North Platte and at Elkhorn near Omaha, and the train had to divide in order to overcome the heavy grade. They finally reached Omaha on October 22 – the train was nearly three days overdue. Allen mentioned that it was also the last train that made the run over the Union Pacific Railroad that winter, owing to a snow blockade that lasted several months.

During the party’s previous hunt, Allen had discussed a winter buffalo hunt with Charles Clarkson, and this was confirmed by a letter. The Allen party departed Omaha for Kansas City and arrived there on the 23rd. That evening around 10:45 p.m. they were again on a train bound west over the Kansas Pacific. By 11 a.m. the next day they were stalled in a snow drift near Bunkerhill. At Bunkerhill they found five freight trains, 11 engines and a snowplow stalled in the snow. At 3 p.m., orders were received that all trains were to remain where they were until the storm abated. At 8:30 a.m. on December 25, Allen’s train, equipped with a snowplow, started on its journey with the temperature at 12 degrees below zero and within an hour, they were stuck fast in a cut. Two freight engines attached to the rear end of a train finally pushed it free and through the cut. Another delay of an hour at Fossil for switching gave the passengers at 11 a.m. an opportunity to have their Christmas dinner-cheese and crackers. This was the first food they had since the previous evening.

Allen’s narrative of his winter buffalo hunt continues:

On the 26th I went to Clarkson’s ranch and found he was at Coyote, fifty miles further west; but there was no train west till the evening of the 28th, when we reached Coyote, at 9:30 p.m. Fortunately the weather had now moderated, and on the 29th we went to Clarkson’s camp and made arrangements with him for another buffalo hunt. At this time, we were in quest of skins for mounting; our summer hunt, as already stated, was primarily for skeletons. Two weeks earlier buffalo had been abundant as far east as Coyote, but they had been so relentlessly persecuted by hunters that they had moved west and were now massed chiefly between Sheridan and Wallace, about one hundred miles to the westward. Between one hundred and one hundred and fifty hunters were said to be in constant pursuit of them. It was roughly estimated that at least 15,000 buffalo had been killed along the Kansas Pacific Railroad during the year 1871.

We were prepared to start on our hunt on the morning of December 31, but the weather turned severely cold and delayed our departure till the following day, January 1, 1872, when we drove south with Clarkson’s outfit for nine miles and then returned, finding no buffalo, and being assured by hunting parties we met that there were no buffalos in that direction. We reached Coyote and then drove north nearly to the Saline River, camping for the night six miles north of Coyote, and the following night on the South Fork of the Solomon, 30 miles from Coyote. The next morning, we went northwest, along the divide between the Saline and the Solomon, to a point opposite Buffalo Station, thence turning north and camping on the North Fork of the Solomon. We saw no buffalo, but were informed by returning hunters that there was a large herd six or eight miles to the northward, where a band of Omaha Indians were hunting them. The next night we camped on a tributary of the Solomon, ten miles northeast of Grinnell. During the day’s drive, we saw a few buffalo about 2 p.m., and were in sight of small bands for the rest of the day, but they were too wild to permit of a near approach. The next day, January 4, we came up with the first old bulls about five miles from camp, but they were wary, and the ground was unfavorable for stalking them. The weather became suddenly threatening and the wind keen and piercing from the north. Clarkson and his partner, Alden, deemed it imprudent to go further from the railroad, as if a storm should overtake us we would be far from shelter and without wood. They decided to return toward the Saline, from which point we could easily reach shelter should a storm render it necessary. We turned southward and in a few miles came upon a small herd of buffalo, from which Clarkson killed five, Alden three, and I got an old bull. The weather continuing cold and the sky overcast, with signs of a storm, we put up our large Sibley tent, which protected us from the wind and served as our base for the next three days, during which, although buffalo were scarce, our hunters secured their loads of meat, and we obtained nearly the desired number of skins. On the return journey we secured two more, reaching Buffalo Station on the evening of the 7th. The station consisted of the section house and two freight cars, one of them fitted up with sleeping bunks and the other serving as kitchen, and a water tank and two or three dugouts. The owner of one of the latter, a buffalo hunter, happened to be absent and Mr. Bennett and I slept in his dugout. Although the entrance was ankle deep with water, and the floor also covered with water, we passed a comfortable night, such shelter as this being far preferable to sleeping out of doors in the chilling south wind then prevailing. We learned here that the buffalo had left the whole line of the railroad, presumably driven off by the 600 or more Omaha Indians we had seen encamped on the Solomon. So, we felt satisfied that we had done as well as was possible under the conditions.

We drove the next day to Coyote, where we finished preparing our specimens and boxed and shipped them. They included eight skins and three heads of buffalo, and skins and skeletons of two lynxes, several coyotes, wolves and jack-rabbits, and a few birds. We settled with Clarkson for $50, which sum covered our transportation and board for a week, and his promise to get for us three more skins of buffalo – two cows and a yearling bull, which were still lacking to complete our series.

We left Fort Hays for the East at 3 p.m. on January 12, and reached Cambridge on the 22nd, stopping by the way at my old home in Springfield for a couple of days to visit the home folks, well satisfied with the results of our nine month’s work in the field. We had collected and sent to Cambridge 200 skins, 60 skeletons, and 240 additional skulls of mammals (mostly large species); 1500 bird skins, over 100 birds in alcohol, and a large number of nests and eggs; a considerable number of fishes, both fossil and recent, and a few mollusks, and many insects and crustaceans.

The following year I remained at the Cambridge Museum, cataloguing and labeling the rapidly increasing collections of birds and mammals.

References:

Autobiographical Notes and A Bibliography of the Scientific Publications of Joel Asaph Allen. New York: American Museum of Natural History,1916. PP 20-27.