On Hunting and Sniping

feature By: Miles Gilbert | June, 21

The Irish team used Rigby muzzleloading rifles while the Americans used Remington and Sharps breechloaders. As readers of this fine magazine know, the latter are still in use in our own black-powder cartridge matches. Also, they are in use by a few of us for hunting big game, because we enjoy hunting rather than sniping.

Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary defines “snipe” as a verb in use since 1832, meaning “To shoot at exposed individuals (as of an enemy force) from a usually concealed point of vantage.” Popular western Author C. J. Box includes the concept in his current novel Long Range, in which an individual had been shot at a distance of 1,600 yards:

High-tech laser range finders…had changed everything. Knowing the exact distance of the target made ultra-long shots possible, because the shooter could adjust his aim to account for all the factors…there were now rifle scopes that were computers in and of themselves and they enabled the shooter to dispense with a subsequent laser range finder. Scopes were now range finders and ballistic calculators…any man could now be a sniper. (Box 2020:12)

“The shooter programs in what the spotter tells him. We’re talking wind speed-crosswinds, updrafts, down drafts, settings and distance. Adjustments need to be made on the scope depending on the atmospheric pressure-how thick the air is….”

“How long does it usually take for a high-tech range finder to determine the distance and all the variables for the shot?”

“On average, fifteen seconds.” (op. cit: 130-131)

“There’s something esoteric and darkly fascinating involved with it. Hitting a target so far away that it can’t even see you fills a man with a sense of lethality and power that’s hard to describe. And once you do the math and unleash that bullet, you actually have time to think about taking it back-but you can’t. It’s either on target or it isn’t. The target is dead before the sound of the shot even gets there.” (op. cit: 156)

I began hunting with black-powder firearms in 1980. That year, I harvested a little “fork-horn” whitetail up Wildcat Canyon, east of Laramie, Wyoming, at 60 yards with a Sharps “Business Rifle” in .45-70. That gun lettered to Brown & Manzanaris of El Moro, Colorado, and was obtained from long-time Sharps collector, Bruce Cady. Next was a 6x6 bull elk shot at a distance of 26 yards with a .72 caliber smoothbore percussion Dixie Gun Works Magnum Cape Gun that I had attached a top rib on to accommodate open sights. Later on, a cow elk was taken at 56 yards with a .54 custom percussion rifle built with an 1841 “Mississippi” rifle barrel. Then, another cow was shot at 90 yards with a Pedersoli Sharps .40-70 and a bull elk was taken at 35 yards with a .665 round ball from an antique percussion rifle made by Thomas Kennedy of Glasgow, Scotland. My last cow elk was shot at 30 yards with an antique .54 percussion rifle made by Charles Jones of London. There have also been numerous chukars, pheasants, and mallards taken with flint, percussion and black-powder cartridge shotguns; but our focus here is on stalking with a rifle.

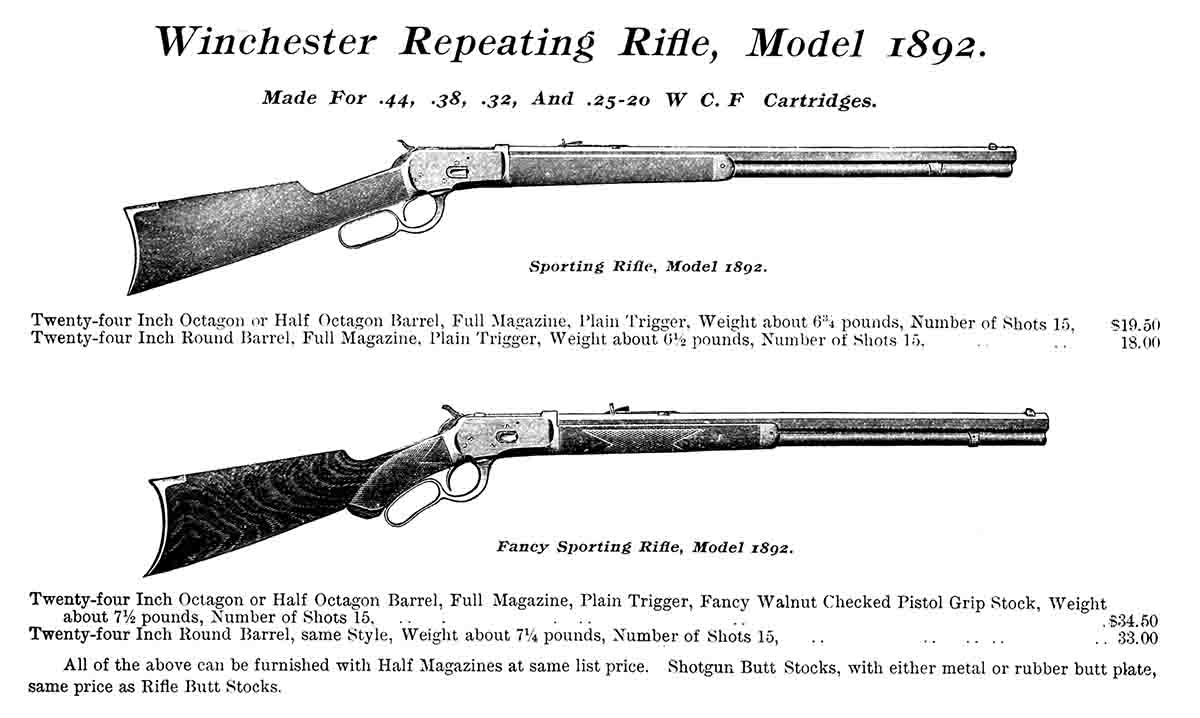

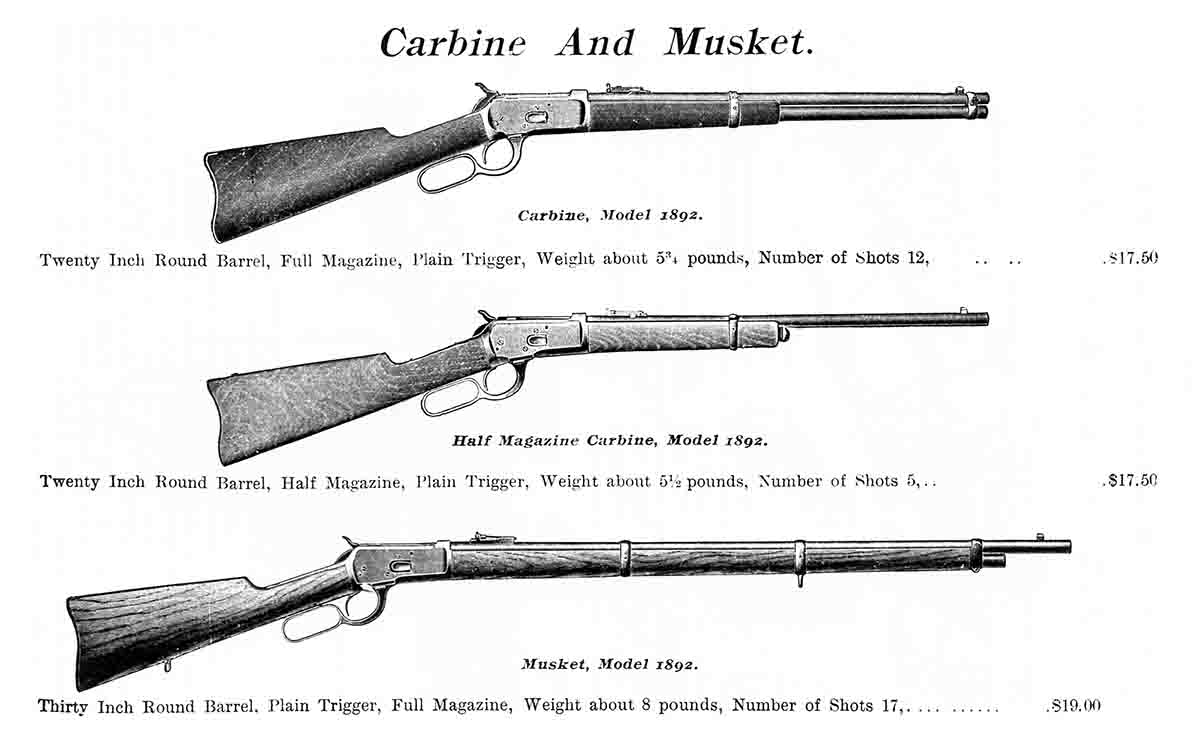

My father borrowed a Model 1892 Winchester in .38-40 from his brother Clyde, who was older by 27 years, for his deer hunting on the Prairie Dog Town Fork of the Red River, a branch of Palo Duro Canyon made famous by the Indian Wars of 1874. He was born James White “Jack” Gilbert, August 30, 1910, the last of eight children born to Charles Clinton Gilbert and Alice White Gilbert, and so he inherited the last and poorest of the eight sections my Granddad Gilbert had acquired by homesteading. I say it was poorest in terms of potential for farming and raising livestock, but it was a hunter’s paradise. Look for the USGS topographic map labeled “Jacks Camp” in Armstrong County, Texas, and you will see some topography very well suited to deer, bear and turkey hunting. The walls of his barn were well covered with sets of antlers. It is rumored that he shot the last free-ranging buffalo on the Prairie Dog Town Fork.

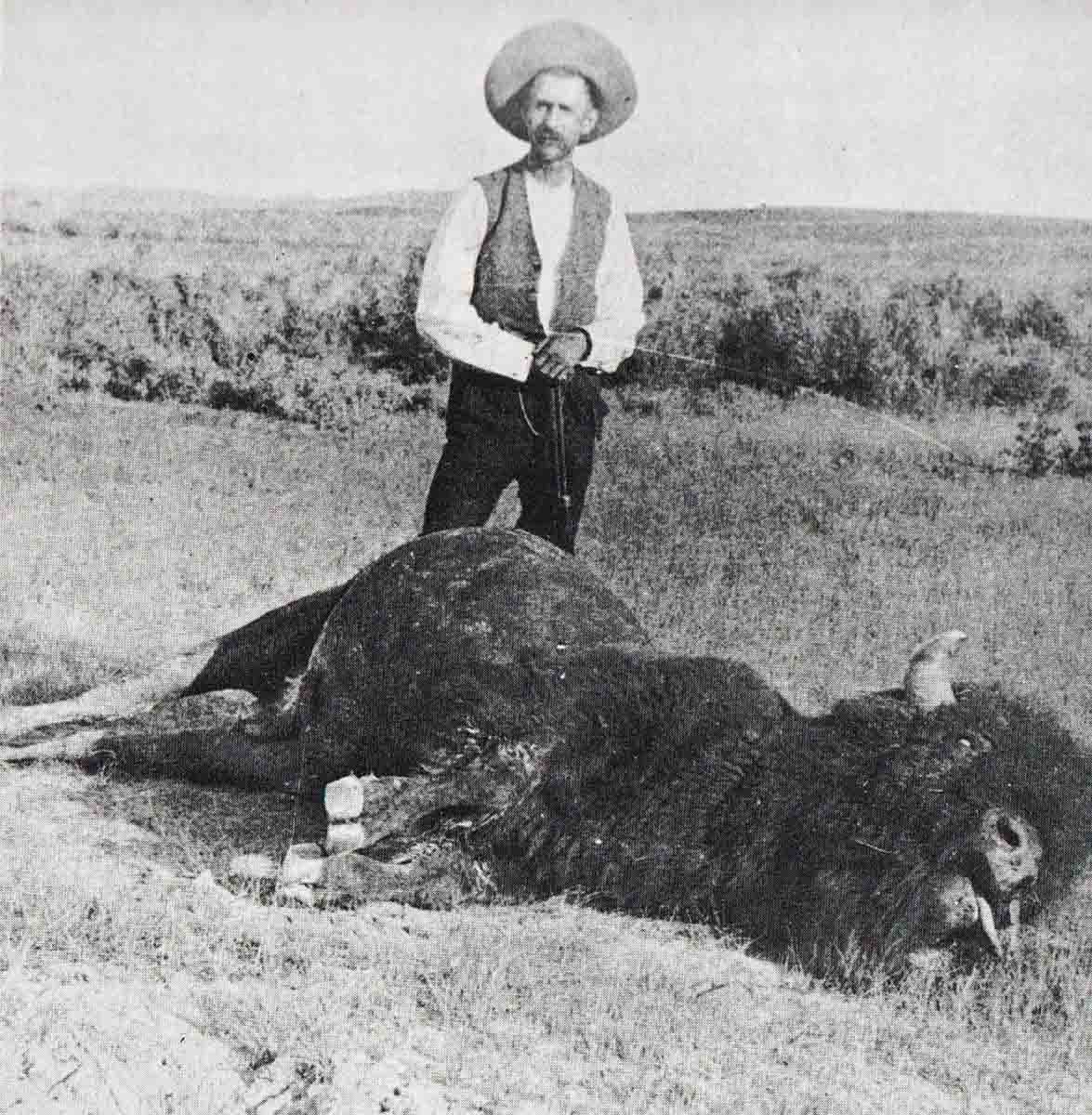

Of course, by the time he began hunting as a teenager, the .38-40 was available in smokeless powder with jacketed bullets. But it and the .44-40 began as black-powder cartridges with soft lead bullets. Even though they are now regarded as inadequate for big game like elk and grizzly bear, the men who used them with success didn’t know any better. Consider the buffalo killed with an 1866 carbine in .44 Henry and the grizzly bear shot with a .44-40 Kennedy rifle by frontier hunting guide and photographer L.A. Huffman. The point to be made is he got close and placed low-velocity, soft lead bullets into the vitals of the animal.

Which brings us to very prophetic statements made by New Mexico Game Warden Walter R. Rodgers, and published by the National Rifle Association in 1949:

The nearest I ever came to finding an all-around gun was a Winchester repeating rifle, of 1892 Model, in .32-20 caliber. Before some Magnum fiend jumps me about that statement, I want to add hastily that I was dwelling at the time in a very brushy area where a hundred yard opening was an extremely long shot. After learning the age-old lesson that regardless of the caliber of the gun, the first shot must be right, with no dependence placed on a follow-up shot, I found the little .32 WCF in the fast-handling ’92 Model to be adequate for anything from squirrels and rabbits up to and including deer, coyotes, wild turkeys, and javelinas. Of course, I learned very early that the slow, loping .32 caliber bullet expelled by so small a charge did not carry the necessary punch after it had galloped over a hundred yards. This in itself was beneficial, since it taught me to hunt. By the word hunt, I mean simply to get all the advantage there is to be had out of stalking and pitting one’s wits against any kind of game animal. I still believe the hunter who gets down to business and stalks his game like an Indian derives more pleasure from his experience and is more apt to fill his bag, regardless of the dimensions of his gun, than the man who places his confidence in a long-range kill.” (Rodgers 1949: 75)

“Well…I reckon they’s been more antelope and deer killed with the old .38s and .44s than any other calibers in the West. Fact is, in later years most cowmen went in for the .30-30, it bein’ much longer ranged and at the same time easily carried on a horse. Them old .30-30s has accounted for a heap of game.”

“I know that’s true,” I told him, “but most hunters today think that even the .30-30 ain’t good enough for deer and antelope now’days. Especially antelope, because they are found in open country that makes it mighty hard to get a shot at one.”

“Bosh!” exclaimed my friend, with a scowl of displeasure on his sun-tanned face. “Them kind of fellers is just too downright lazy to hunt. That’s what’s the matter with them. Why we used to kill antelope regular with them old .38s and .44s, and we didn’t cripple any to wander off and die on the range either. When you plug one through the heart or neck with a good old .38-40 bullet, he’s going down. They ain’t ever made a gun that will kill an animal deader than them old guns did.”

“I know that’s right too, I agreed, but we’ve got something to consider here that I’m afraid often passes us old-timers up. That is, most of the sportsmen that come out every year are town-dwelling citizens. Those fellows don’t ordinarily have a chance to shoot a gun half a dozen times a year. Even the ones that shoot on ranges, and are in good target practice, they don’t get a chance to live among game like we do. What they don’t know about stalking game, plus the time they have to spare for the hunt, usually places them on the losing end of the deal. If they didn’t use long-range flat-shooting rifles, they wouldn’t stand much chance at getting an antelope buck that can smell danger plumb across the rotten Pecos and lope into the next county before the sportsman can get sight of him.”

He replied “…if you had this here half-mile rifle and a powerful glass to sight through, how long would it be before you’d quit stalkin’ yuh game and go to bangin’ away at it as far as yuh could see, like some of these here so-called sportsmen does?”

“Reckon I wouldn’t,” I told him simply, “and neither would you. Once a man learns his shootin’ range, and is sportsman enough to respect the game and the other fellow’s right to share it, he quits riskin’ them long possibles. We like to own a gun that we know will shoot fast and flat, though we know our shootin’ range at live game is a very small portion of the gun’s possibilities. It’s my personal opinion that the first essential to clean killin’ is to be hunter enough to stalk your game, takin’ advantage of whatever type of cover the country affords. Get up close as possible and make a clean humane kill. That affords more lasting pleasure to the true hunter than all his long shots could ever provide. Then, just in case something does get wounded, and a long shot is the only hope of putting it out of its misery, you’ve got a gun that’s equal to the occasion-provided yuh can shoot it.”

The old-timer replied, “I still maintain that shootin’ too far with them long-range guns is doin’ more harm than good. They’s too many fellers goin’ out every fall armed with what they figure will kill his antelope or deer as far away as they can see it. They think that because they can see an antelope a half mile away, and can’t see no way to get up closer they ought to have a rifle that will kill him out there where he is. They’ve got ’em too, rifles and sights that will hit and kill at incredible distances. But the chances are too great against connecting with the right spot at them distances to make a clean kill. They shouldn’t shoot that far, even if their guns are capable of it.” (Rodgers 1949: 146-149).

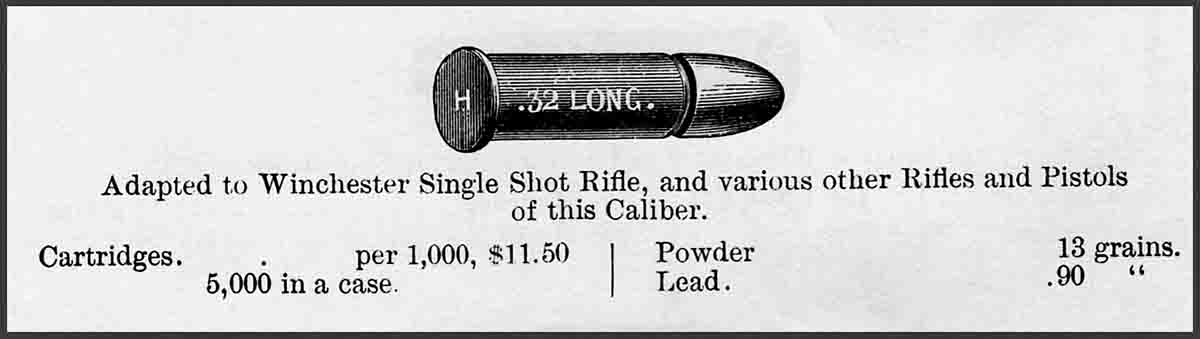

Alas, I no longer have the exact citation for one of Lucien Cary’s delightful short stories that appeared in an early Gun Digest, but the gist of the story was about the most famous, most successful deer hunter in Pennsylvania during the late 1890s until his death about the time the U.S. entered World War I. Upon news of his passing, many hunters wanted to buy the old man’s deer-killing rifle, until they learned that it was a humble Remington Rolling Block chambered in .32 Long Rimfire. The greatest deer killer was a hunter, not a long-range shooter.

I recognize that physical disability may require a sportsman to obtain the sort of weaponry that can make him a sniper, but I encourage all of you who are “young and able” to learn to hunt by stalking.

Resources:

Box, C.J. – 2020 Long Range. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York.

Brown, Mark H. and W.R. Felton – 1955 L.A. Huffman Photographer of the Plains: the Frontier Years. Bramall House, New York.

Rodgers, Walter R. – 1949 Huntin’ Gun. National Rifle Association, Infantry Journal Press, Washington.