The Wyoming Schuetzen Union's "Center Shot"

column By: Staff | November, 19

“If it were not for the cranks, experimenters, investigators, or whatever name they might be called by, the world would come to a standstill and cease to move, while the old fogy class might say, “No matter, things are well enough as they are.” The writer belongs to the first class, and is always looking for something new and novel, that is, at the same time, a real improvement”. These are the words of Rueben Harwood, written in 1893, summarizing his own viewpoint on progress. Harwood gave our ancestral riflemen the .22 Harwood Hornet, a pairing of his novel concept of a high-speed rifle bullet driven by black powder with the notion of necking-down an existing case (here the .25-20 S.S.) to accept a smaller caliber bullet.

In Boston not long previously, a relatively green fellow shooter with a personal demand for precision had turned a simple brainstorm, borne of observation and deduction, into an article that revolutionized how a generation of riflemen looked at their match bullets.

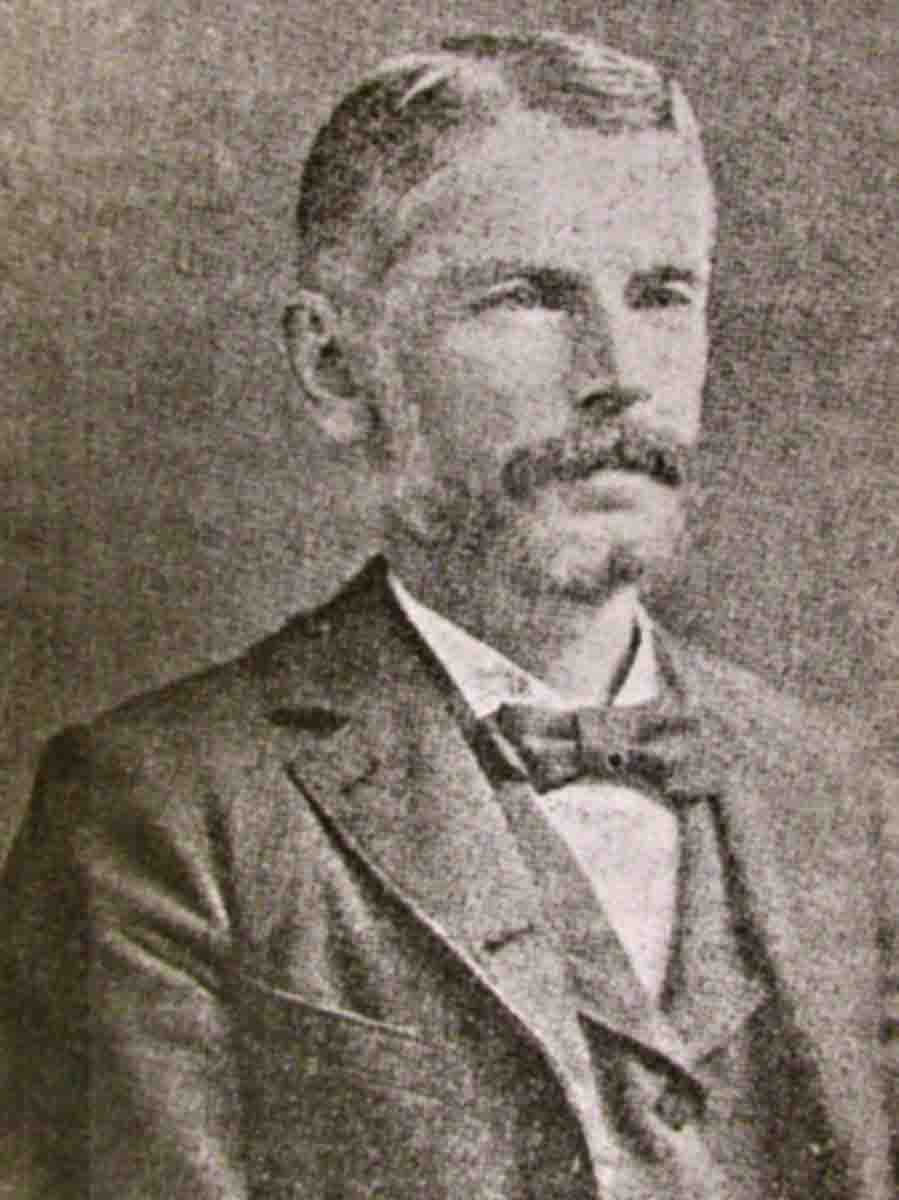

On May 15, 1841, Daniel La Forest Chase was born in Grofton, Massachusetts. His mother, Sarah Pursis Chase, was the parent furnishing the surname. His father was David Greenwood. Young Daniel was raised in Grofton and went to high school in nearby Newtonville. He went on to Harvard University, graduating with the Class of 1864 with a degree in business.

That summer he travelled to Chicago to partner with his father in the making of confectionaries, using machines they had designed and built themselves. Three years later in 1867, young Chase was engaged in making a similar set of machinery for a European order. That fall he sailed to England to superintend setting it up. He returned to Boston the next year. In 1871 he moved to Winchester, Massachusetts, where he lived with his aging father and continued in the same business. From 1867 to 1881, Mr. Chase was busy inventing and patenting a handful of steam generators, engines and other steam-related equipment. The Harvard Secretary’s Report of 1871 contained the notice that D.L.F. Chase chose to be known as an “inventor and machinist.”

We would almost expect a precision-minded, mechanically inclined individual with a background similar to Mr. Chase’s to become attracted to rifles and the discipline of rifle shooting. Few of us would be surprised if, once smitten, this person would become quite skilled and embraced the sport with a life-long passion. We all know someone like this.

1885 was the year that D.L.F. Chase became interested in rifle shooting solely as a recreational undertaking. He joined the Massachusetts Rifle Association, bought a Ballard rifle chambered in .38 Rimfire, and started shooting at the club’s famous Walnut Hill range. Almost instantly, he was made aware that he’d outgrown his entry level outfit, and invested in a more suitable Ballard .38-55, to which he attached a Vernier aperture sight with fine windage adjustment, designed and fabricated by Chase himself. He progressed to becoming adept with a bullet mould, reloading tools and other implements of the successful rifleman.

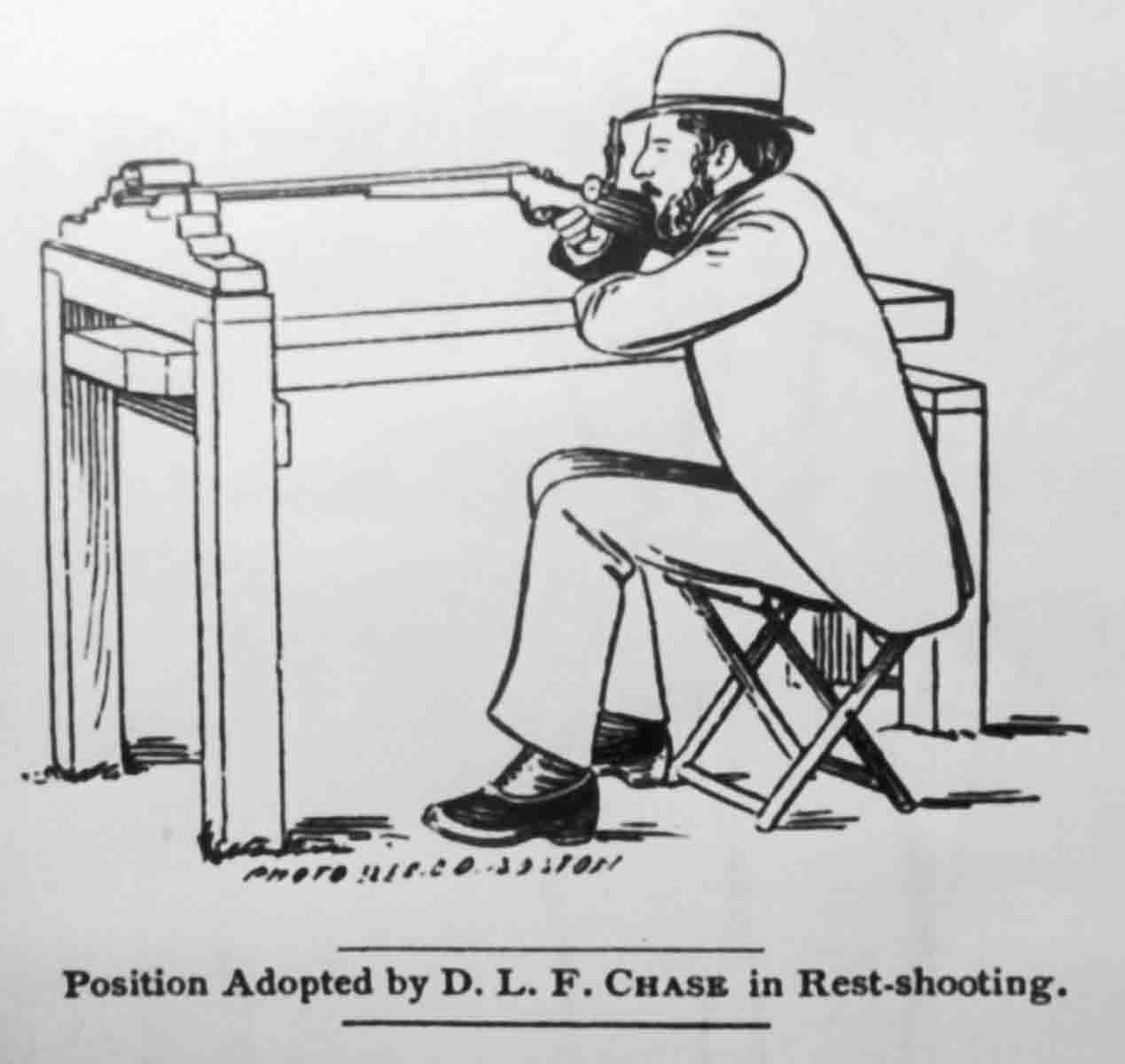

Physically, Mr. Chase was slight in stature and far from robust. Shouldering a 12-pound Schuetzen rifle and firing a typical match was beyond his physical capability. With this inherent limitation, Chase gravitated to rest shooting, the allied pastime much better suiting a man dealing daily with exactitude as his goal and demanding precision as the result.

The Massachusetts Rifle Association was founded in 1875. Walnut Hill, the club’s home range, was completed on June 19th of that year and the first bullet over the new range buried itself in the fresh berm on November 10th. The range facility served Boston and several outlying towns. Walnut Hill quickly became the most noted civilian rifle club in the U.S. and its significance was rivaled only by the great Creedmoor range on Long Island.

1881 was the year that Walnut Hill nailed together its 200-yard, double-rest benches. This new form of shooting was belittled by those who did not consider rest shooting to be a true test of marksmanship, but the scoffers were to discover that this new discipline required considerable skill. Rest shooting became very popular and the club held weekly rest matches. At the time competitors shot at the Massachusetts Decimal Target, hoping to perforate its 3.50” ten-ring.

The 200-yard bench became Chase’s element and where he would shine. Here was where he rubbed elbows and forged relationships with other kindred souls such as F. J. Rabbeth, C. W. Hinman, E. E. Patridge and Salem Wilder as well as many others of the club’s August membership.

Chase welcomed the challenge of the bullseye and devoted himself to bettering his rest technique, equipment, and mental attitude. His level of self-application paid off. Later in 1885 Chase celebrated his first “possible” on the Decimal Target.

Many of the Eastern clubs switched to the Standard American Target the next year. This had a ten-ring of 3.36 inches. The Standard American Target was modified in March of 1886 to include two inner rings; the new 11 circle was 2.33 inches in diameter, and an inner ring worth 12 points, a scant 1.41 inches. A “possible,” or perfect score on this new Standard American Rest Target was now 120 points. Higher, more meaningful scores was the design and the outcome.

After nine months of progressing, Mr. Chase shot his first ten-shot, one hundred point possible on the Standard American Rest Target on June 5, 1886. Major Ned Roberts erroneously credits H. L. Willard with the achievement in 1895. Perfect scores, at the time, were remarkable accomplishments worthy of national mention. Six months later, Chase’s second was recorded, and two more yet before November 1, 1886. By year’s end seven other perfect scores were shot by Walnut Hill’s rest shooters.

D.L.F. Chase distinguished himself early in his budding career and came to be regarded as one of the top rest shooters not only at Walnut Hill, but in the country as well. Confident in his own shot-calling and instincts, Chase questioned whether he was getting from the target all that he was holding for. He investigated by walking the ground beneath his bullet’s route from muzzle to berm, casting his gaze watchfully and expectantly. He did this repeatedly to validate his initial findings. Along the way, he encountered a sparse litter of patch paper of various lengths and at various yardages. He bent down and sifted through the earthen butts, locating many of his own bullets and plenty of those of others. The majority had shed their patch as they should. Though battered, some few bullets still held a double wrap of paper. To others, varying lengths of paper scraps were stubbornly still attached. This eye-opening discovery shined a beacon’s light on the chief reason for Chase’s off-shots; the patches were not uniformly leaving the bullets, and this was interfering with the true flight of the projectile.

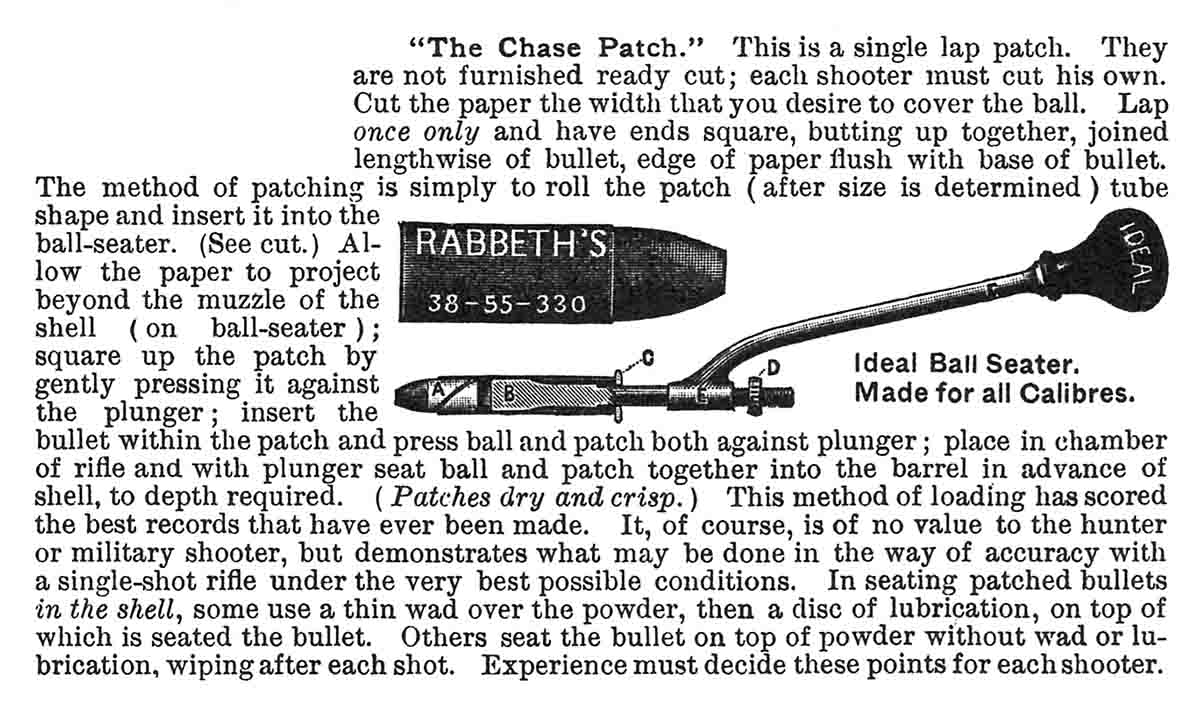

Though a novice, Chase brought into the rifle shooting sport a beneficial skillset, partly innate, partly acquired. He possessed a keen analytical and diagnostic capability to guide him through trouble-shooting the failures in a mechanical system. In the mind’s eye of the mechanic, Chase envisioned the proper paper patch parting company with its carrier bullet instantly upon spinning out of the barrel, then fluttering down to settle atop the patch preceding it, while the perfectly patchless bullet proceeded unencumbered to the target. Mr. Chase’s analysis, based upon the evidently here and there scattering of fragments of the seemingly flawless standard double-wrap patches, was that there was a crying need to reassess the obviously flawed status quo. Chase surmised that the too tightly wrapped patch with its slight built-in wrap overlap, together with the problematic and binding twist of paper trailing at its base, were the troubles to be addressed. To this end, Chase conducted his own trials, focusing on a single wrap of a more substantial thickness of paper and the elimination of the irregular and unavoidably asymmetrical tag-end altogether.

Mr. Chase then devoted himself to devising single-thickness patches for his .38-55 Ballard. Properly thick paper was square cut on a template to precisely butt patch edges and after a bit of trial and error he formed them into cylindrical form around a common pencil. Rolling these singly thick patches developed into an easily acquired talent.

Fired patches were localized and when recovered, showed the hoped for rifling impressions. In terms of accuracy, this new patch system showed great promise.

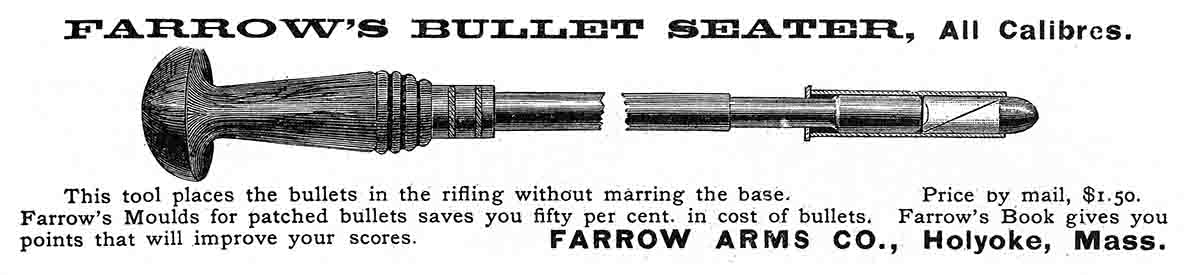

The word travelled fast around Walnut Hill and Mr. Chase informed the wider audience of fellow riflemen of his improved alternative to the double-wrapped paper patch in the July 19, 1888 number of Shooting and Fishing magazine. Here he nut-shelled the preparation of the patch and its gentle insertion past the chamber and into the barrel via the bullet seater that readers were all familiar with. Too, he outlined advantages he considered important, namely the avoidance of the disruptive “bunch or fold” on the double-wrapped bullet’s cylindrical surface, and the elimination of its unnecessary paper tail.

In answer to subsequent reader questions regarding the bullet seating operation, Chase filed a second clarifying report in November 29,1888, offering tips to accomplishing this procedure correctly. To begin with, the bullet needed to be seated properly. While the usual practice was to seat bullets with the muzzle slanted downward, Chase’s patch required a slightly elevated barrel to ensure that there was no tendency for the bullet to partially slide out of the single wrapped patch. The patched bullet then needed to be eased into the breech with the bullet seater, done without an abrupt thrust which might jump the bullet ahead of the patch. The bullet seater needed to be properly shaped with a snugly fit chamber and a flat, square-ended plunger so the patch could not slip off the bullet or become pinched or nipped. After seating the bullet, Chase advised to use a second plunger to seat the bullet a trifle ahead of the case. To those that missed Chase’s 1888 tutorial, the Shooting and Fishing “Question and Answer” columnist in 1890 reduced his explanation to its barest essentials – “One wrap, edges butt.”

Riflemen took notice. The word spread and the Chase Patch took hold. Within five years after its introduction, the single-wrapped Chase Patch had supplanted its predecessor almost altogether among American target-shooters.

Like every other competitor, Chase saw the need to avoid an accumulation of accuracy-destroying black-powder fouling. After considerable trial and error he arrived at an ultra-simple procedure that worked as well as anything he’d tried. First, there was the ritualistic passage of a water wet Fisher brush (a short spiral bristled brush beneath a set of spaced rubber washers to expel the water) followed by a tight dry patch – once in and out. His readers were urged to follow his example. Chase’s method became widely practiced.

John Barlow built a successful reloading implement business by catering to the needs and whims of the American shooter. After founding Ideal Manufacturing in 1886, Barlow endeavored to keep abreast with the times and remain progressive. When the up-to-date 1890’s rifleman needed bullet seaters and the Ideal Patented Cylindrical Adjustable bullet mold, Ideal was ready with the goods by March of 1891. Barlow’s Ideal Handbook even spelled out detailed, understandable instructions for preparing both the new Chase and the old double-wrap patches. Many riflemen learned of Francis J. Rabbeth’s outstanding fifteen consecutive Chase-patched .38-55 bullets in a two-inch circle at the Walnut Hill 200-yard range through Barlow’s sly inclusion in several editions of his Ideal Handbook, the vade mecum of the American Riflemen.

Incidentally, Francis J. Rabbeth was more familiarly known among the rifle shooting fraternity as “J. Francis.” Similarly, about 1891, Daniel La Forest Chase became better known to the Walnut Hill crowd as “F. Daniels.” Most rosters of Massachusetts Rifle Association. competitors carried Chase’s “shooting name” and no other. Chase’s (Daniel’s) friend and fellow rest shooting enthusiast J.E. Kelly went along and chose to be known by “R.L. Dale”. Another of Chase’s intimates answered to Charles W. Hinman. At the range, he was “W. Charles.” During the 1880s and through the earliest years of the twentieth century, it was a very common practice to use a pseudonym to sign a contribution or letter to the sporting periodical. Examples number into the many dozens. The extent of the widespread use of “shooting names” or if it was unique to Massachusetts Rifle Association members is unclear.

Mr. Chase was particularly involved and active in the administrative affairs of the Mass. Rifle Association Early on, he was routinely elected to its board of directors, and later served as its president for at least nine terms.

After putting 8,000 shots through his Ballard .38-55 it was still as ten-ring capable as ever, but by 1889 a long string of tens on the Standard American Rest Target didn’t mean what it once did. Aspiring to better, in 1891 Chase obtained a new heavy Ballard barrel as a replacement, but sustained trials didn’t improve indifferent groups. He tried old tricks and some new ones, and ultimately the new barrel surrendered. He wrote an essay titled “Conquering a Stubborn Barrel “for the benefit of his fellow Shooting and Fishing readers. The new barrel now proved to be more accurate than the original and with it he once made a run of ten consecutive twelves (in parts of two scores) and later posted his personal best of 117 points. By this date, Chase was using the more commonly used and accepted telescopic sights.

At some point, Chase’s old Ballard barrel fell into the hands of Judge Edwin J. Crom of Biddeford, Massachusetts, a strong offhand rifleman with a cranky idea to re-purpose the barrel. He placed it in the center of a length of gas pipe and filled the space in between with molten lead, increasing its weight to 22 pounds. Judge Crom shot the heavyweight gun at the National Bundfest in 1895.

In 1893 Chase’s Ballard was fitted with a third barrel, a #4 weight Winchester tube. It too, turned out to be a particularly stellar performer. In March of 1894, Chase ran up thirteen consecutive “twelves” in two scores and a new high of 119 points. Ned Roberts was able to authoritatively record that Chase did manage to record “a number” of perfect scores of 120, probably in the mid-1890s.

The Chase Patch system remained in general use and preference until it fell out of fashion just before the dawning of the twentieth century. At that time, the paper-patched bullet in Schuetzen and rest rifles had been outmoded and supplanted by the grooved and lubricated cast lead bullets as riflemen advanced with the times.

About 1900 the Eastern rifleman was wholly caught up in the new craze of military rifle practice and shooting the national arm. Movement forward was hindered by the lack of suitable, safe rifle ranges beyond the 200-yard limitation of most rifle clubs. The Massachusetts Rifle Association answered the call and met the need of the U.S. National Guard and its own membership when on July 27, 1901 opened its new one thousand-yard range. Over a short stretch of time, it became the habitat of D.L.F. Chase. For a while, he divided his time among the other Walnut Hill ranges, but there was a bewitching, beckoning allure to the long range from which he could not turn away. For the next several years the bulk of his range time was spent at the thousand-yard mark. There was no shortage of shooting opportunity. Inter-club matches and mid-week practice was available almost year round. In 1904, a heated shed was provided to the die-hards as a winter time refuge.

Chase may have started with an issue infantry Krag, but in a short time felt the need for better accuracy from his “target rifle” and got Harry Pope to re-barrel the gun. Pope worked his magic and turned it into a first-place winning outfit. At some point, Chase picked out his “match” rifle, a Pope-barreled Remington Hepburn, also chambered in .30-40. Both rifles wore telescopic sights. He then proceeded to thoroughly immerse himself in this newest undertaking. Over the next several years Chase continued to demonstrate the same championship level of ability and his expected participation in the advancement of the new branch of shooting. He continued to master the service rifle and its ammunition while, like it or not, dealing the metal patched bullet of the future and contending with what nature would do to thwart his success along the way. He, and by extension the American rifleman, learned as he went along.

Mr. Chase had a friend, a range companion and fellow habitue at the long range in Charles W. Hinman. This like-minded duo practiced together, compared notes and competed formally and informally. Hinman had a Pope-Krag and a specially throated Winchester High Wall also chambered in .30-40. At the Massachusetts Rifle Association 1905 Thousand Yard Fall Match, where D.L.F. Chase reminded the assembly that he’d been shooting the rifle for twenty years, Chase and Hinman tied for first place.

Hinman and Chase together acquired a knack for long-distance wind doping. On March 10, 1906 “F. Daniels” and “W. Charles” were at the thousand-yard point in a shifting nine o’clock wind strong enough to require at times 22 feet of windage allowance. The two managed to keep three 10-shot strings of the 220-grain bullets all on the target, though scores did suffer. During an icy gale on February 8, 1908, Chase discovered that his summer’s elevations required 20 feet of correction and 19 feet of windage to find the 1,000-yard target. Chase hadn’t entirely ignored the two 100-yard range, or his Ballard .38-55. In January 1906, he made a great run of thirteen consecutive twelves at the 200-yard rest target.

Mr. Chase was aware of the chemist’s warning that combining grease, bullets and rifle bores left behind a burnt grease and powder-fouling compound that was difficult to remove. Still, it went against the trained mechanic’s grain to send an unlubricated metal-cased bullet down a Pope rifled bore. “It is like using a fine razor to open an oyster or a silver ladle to stir the fire” President Chase told his audience at his address to the annual Massachusetts Rifle Association meeting in January of 1906.

Familiar with the lubricating properties of graphite and its negligible effects on steel, he arranged an experiment. He dusted the fine, soft carbon onto the bullet ahead of the case of a supply of his Krag handloads and sent them to the target. Results were unsatisfactory and inconclusive. He then painstakingly lathe-turned 10 to 12 shallow grooves, only .005-inch deep so as not to weaken the jacket, into a goodly supply of bullets. He then rubbed on a film of light oil and pressed the graphite into the grooves, leaving a thin film of graphite along the bearing surface of each. Results at the target were disappointing, but a squint down the bore showed that the hoped for lubricity had been achieved. Chase left the range disappointed and the project relegated to back-burner status.

Mr. Chase was a practiced judge of wind and a skilled hard-holder, when shooting from a rest. Still he wondered what to blame for the wild shots he’d been pestered with. “I do not know why I get scores with five or six bullseyes and two misses sandwiched in among them” he went on. At his thousand-yard bench he placed a thermometer and kept an eye on it to determine if temperature variations affect point of impact. His Spring 1906 plan was to sink a post at the thousand-yard point, affix a telescope and center the crosshairs on the bull to see if they stayed put through the changing weather, light, and seasons. He considered the unconsidered variables such as the effects of shadows and sunlight on sighting, holding and sight picture. Chase weighed each of his .30-caliber rest bullets and gauged the squareness of their bases, and trued those in need with an implement of his design and fabrication. All the while, he didn’t seem to stray from the universally used powder charge – 36 grains of W.A. These projects developed into an ongoing struggle and a work in progress. The variables magnified with the distance and he was shooting from the thousand-yard point where “my mind has been most of the time” he said in January of 1906.

Chase was among a small group of the prominent experimenters of his time, each with a scientific turn of mind, and sharing the pursuit of the common goals of a better understanding of ballistic principles, accuracy improvement, and a firm grasp of the mechanics involved. F.W. Mann, Perry Kent, Walter Hudson, Charles Newton, together with a scattering of lesser-knowns, were determined to, as Dr. Mann expressed it, “wrest from the rifle its secrets.” These individuals worked mostly independently but their successes and failures became well-known via the grapevine of the period, the rifleman’s press. The exchange spurred further investigation and invention and educated the common rifleman. Everyone involve benefitted.

Chase’s thousand-yard scores 1906-1909 were generally ahead of the pack. Early in 1908, his pet Krag began shooting erratically, and after 1,300 high velocity shots, it was ruined for the long range. Most of his peers counted 3,000 shots as their useful barrel life. He had Pope rebarrel it for what was likely the last time.

About the time the 1903 Springfield rifle saw its first use at Walnut Hill in the spring of 1908, Mr. Chase became suddenly absent and was not seen on the range again until the January 1909 1,000-yard shoot. It was thought that he was experiencing another of his prolonged spells of illness. One year later, in March of 1910, “F. Daniels,” now 69 years old, proved that he was still a thousand-yard contender, when his 46X50 was the high score.

There was no magazine mention of D.L.F. Chase or “F. Daniels”, after July of 1910. The Walnut Hill standout died at 79 years old in Quincy, Massachusetts, on May 21, 1920. Never the picture of health, he somehow managed to outlive most of his rifle club contemporaries. Chase was never well-known or gained an exposure outside of a localized circle. Still, he contributed significantly to the rifleman’s progress and it’s time he got his due. -Jim Foral

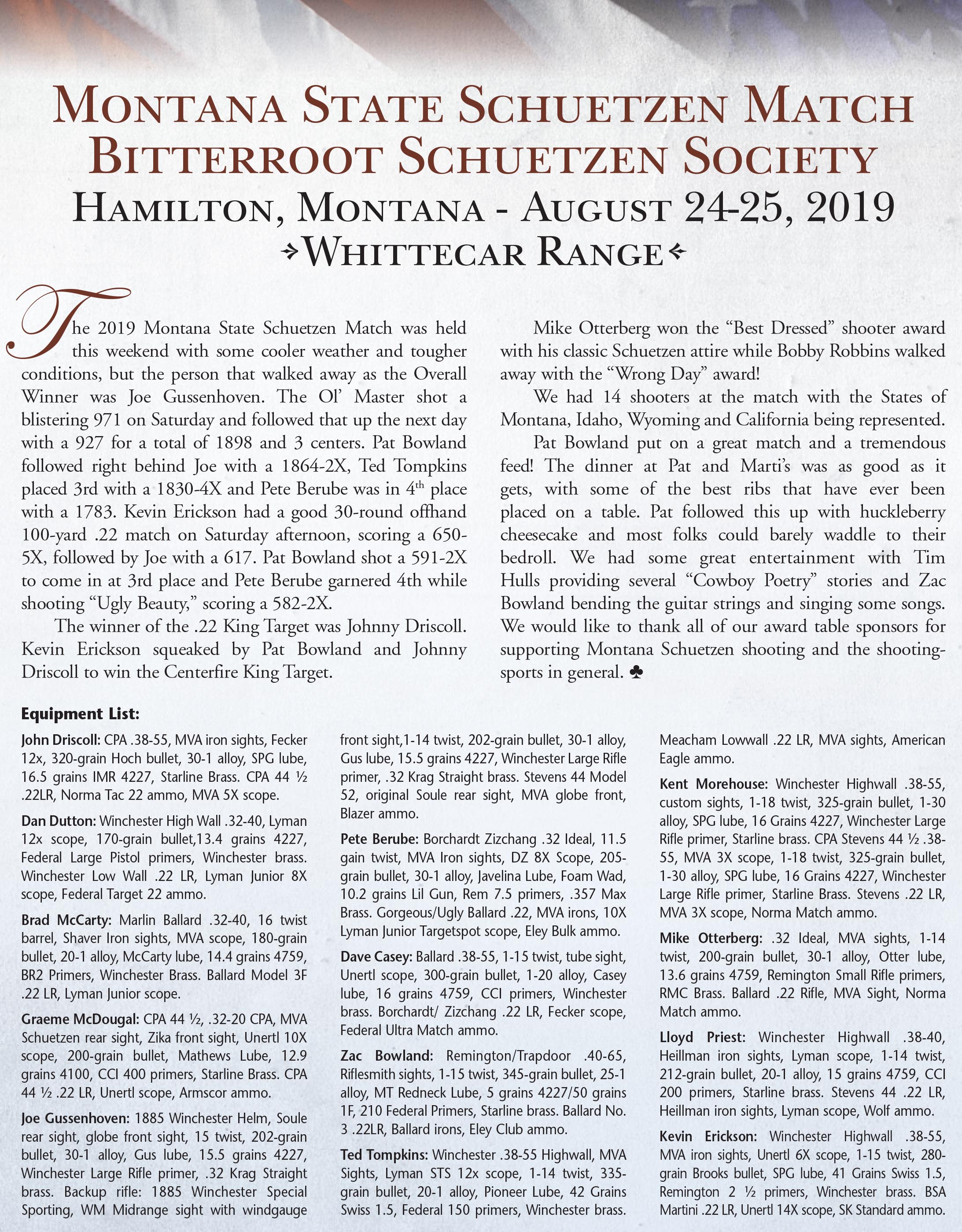

Montana State Schuetzen Match Bitterroot Schuetzen Society

Hamilton, Montana - August 24-25, 2019 Whittecar Range