The Rifle and Fall of Recreationo Magazine

feature By: Jim Foral | December, 23

Enter George Oliver Shields, who challenged himself to make a go of it. Shields was an established writer. His by-line was well known but his nom de plume “Coquina” was probably better recognized, and Shields used it very often side-by-side to his name. Shields’ most active and creative stretch was between 1889 and 1900, and his best-known book was his 600-page, The Big Game of North America. His Camping and Camp Outfits may have been the earliest serious treatise on the subject.

Shields recognized the need of the ground floor opportunity to market a monthly periodical appealing to the outdoor sporting enthusiast, who had nothing of this nature devoted to his particular interests. Shields’ pioneering effort predated by five years the appearance of what would be a similarly formatted Field and Stream and Outdoor Life, both on the scene just before 1900. His acquaintance with the publishing business made a magazine such as the one he was deliberating less risky than it might have been.

With a shoestring capital of less than $3,000, Shields started in the magazine business in 1894. He put out the first edition of 5,000 copies of Recreation in October of that year. Volume No. 1, Issue No. 1 was 48 pages, 19 of which were ads that Shields had scurried to obtain. His office furniture consisted of a second-hand chair in a printing loft at 216 William Street in New York City. He ran all his own errands, did all the lifting, wrote all the copy, put up his own packages of samples and subscription copies, and hauled it all to the post office. He did all of the work but hired a stenographer to type and keep the books.

The American News Company, the great New York book, magazine, and newspaper distributing center got 2,000 copies of the first run. What that agency couldn’t move was returned to Shields, and these surplus issues were distributed in his promotional efforts. In a year, the business needed a three-room office space. In 1897, three years from start-up, Shields had leased an entire floor of a building for a force of 16 staff to service a reported 65,000 subscribers. The October 1897 issue of Recreation ran 144 pages, 66 of which were advertising. Various friends of Shields had predicted a life span of three to six months before bankruptcy. That October of 1897, Shields was able to gloat with delight, “I now metaphorically spend hours with my thumb to my nose, wriggling my fingers in their faces.”

Physically, the new magazine was strikingly handsome, and Shields kept the same pleasing look to his covers – front and back – for a long stretch of continued production. Each cover was tastefully illustrated with an appropriately outdoorsy photograph with reddish tones replacing the less festive black, and placed on a faded yellow field that substituted for the customary drab white. This improvement over status quo stood out on the newsstands, and the familiar color scheme shouted “Recreation!”

The short blurbs found in the popular reports from the Game Fields gave readers a chance to see their name in print. Recreation’s gun column was essentially entry-level material with an occasional nugget of industry news. Many of the men considered to be “old timers” contributed tales of their pioneer days, conjuring up mental images of skies black with ducks and wild pigeons, and the plains choked with buffalo and prairie chickens. Most of the subscribers seemed to be urban dwellers that could only imagine what was seen in the West a generation previously. One example followed another before petering out altogether. It was a nice benefit provided by the editor.

Amateur photography, a rage of the times, was a growing and popular activity, and one not ignored by Recreation. The magazine conducted its own highly technical, chemistry-intensive column that covered the demand for it. Change in the film developing stage was in a perpetual state of improvement, and Recreation made sure it kept up. The several pages each month devoted to the photographic topics were an actual public service. The Photographic Department was a popular segment of the magazine, one that required a certain expertise. It was probably not written in house. Shields made plenty of room available in the Photography column for the extra advertising it drew, and the line illustrations that accompanied the ads. It was good sense and good business.

Overall, there was a general sense of quality to Recreation. To the extent that black ink and the white page could accomplish it, the pages were very artfully and plentifully illustrated. In the main, Recreation content issued from the typewriter of its editor. There were no staff writers and no one on the masthead – or even a masthead. The magazine’s flow was faultlessly lively and varied. The target readership was the average outdoorsman with average intellect and average means. A model for other magazines to follow, the budding Recreation probably set a good example.

Shield’s soapbox – The Editor’s Corner – probably achieved its objective of making the readership aware of their outdoor world, their effect on its biological resources, and the essentialness of personal moderation. The editor was a gifted and effective communicator, a provoker of thought, and a shaper of opinion. Columns were added or deleted depending on reader input or editorial whim. Recreation was a work in progress and George Shields was developing and setting a standard for every sportsman’s magazine to follow.

In mid-1898, G.O. Shields instituted the League of American Sportsmen, which became the unofficial cause of the magazine. The LAS favored more restrictive game laws and the sportsman’s adherence to bag limits, seasons, and the letter of the law. If Recreation needed a gimmick or a cause to champion, the LAS served as a good choice that fulfilled its purpose, and had the added benefit as an attractant for new subscribers and advertisers. Not Shields’ secondary consideration, certainly, as it was a generator of income. Recreation was its official organ and members of the LAS invariably subscribed to it. LAS dues were $1 annually, life membership and LAS badges and insignia were also available.

Shields’ success was also measured by other criteria. He was particularly heartened by the “many thousands” of letters from men who candidly admitted to once having killed all the game that they could, whenever they wanted, and never considered that they were doing any harm until their eyes were opened by the continual chastisement in the columns of Recreation. They had seen the light, they indicated, and were directed onto the straight and narrow path leading to reform.

Hard work and good planning paid off. At the end of Recreation’s first year, Mr. Shields moved uptown and had his printing done at another facility. Six months later, he moved again to a space where he lived and worked until 1904. Subscriptions had grown rapidly, as had newsstand sales. His subscription books in 1904, contained or claimed 32,000 names, and the American News Company handled the same number of issues every month. Page count had grown to 144 pages, half of them being advertisements. Shields now employed 15-17 people in the summer, 18-24 in the winter months. Things went swimmingly…until they didn’t.

In late 1899, Shields raised his advertising rates, and Marlin reacted by removing their ads from the magazine. In reprisal, Shields published sham letters purporting to be from correspondents that reflected poorly on Marlin, and making false and slanderous statements about the company’s goods. There were four of these fabrications within the course of a year. It was Marlin’s contention that Shields pulled his shenanigans to compel the New Haven gun maker to get back into his fold of advertisers, and to “gratify his malice.”

Marlin brought suit against Shields individually in June of 1902, with the fervent hope that Shields would “perpetually refrain” from writing such things about Marlin in the future. Marlin never advertised with Shields again, and other gun makers took a hard look at following suit.

When late in the year of 1902, Peters, Marlin, U.M.C., and Winchester all abandoned their advertising presence in Recreation, they each became aware that there would be a price to pay. They may have expected some direct retaliation but they couldn’t have foreseen an original tactic straight out of the underhanded playbook of George O. Shields.

The Guns and Ammunition column of the September, 1902 issue had a series of phony letters directed at all three prodigal advertisers. The first of these was from a “subscriber” in Cleveland who thought that the U.M.C. people could improve their Savage .303 bullet by extending the jacket a trifle further up the bullet.

This was mild compared to the subscriber’s treatment of Marlin: “We had three Marlins in our club in 1900. They were the cause of more profanity than all other annoyances put together.” Another began “my special favorite is a Marlin (please don’t laugh) with Lyman sights.” He went on and hit two targets with one paragraph: “I am not fully acquainted with the Winchester, but doubt if I should ever like it as well as I could like the Marlin – if it would only work right. However, I am disgusted with Marlin’s attitude in this matter, and unless it changes will lose customers in this country. I should think that it would pay him to hire a man to read Recreation and learn what is the matter with his gun, then fix it properly and tell his patrons through this magazine that he has done so. The Peters Company too would better follow the same line. When they communicated to Recreation that the fault of their cartridges has been remedied, then my friends and I will try them again.” This above was over the mythical signature of “M. C. Kissinger.” And this is just a sampling of what awaited anyone crossing G.O. Shields.

Letters suspiciously too numerous and too well-timed, while bearing the other earmarks of invention, crept into the September, 1902 Guns and Ammunition column of Recreation. One of a small cluster of them meant to punish Peters was from a Minnesota bird hunter who found himself stuck in a small town where the only shot shells to be had were from an overstock of the slow-selling Peters brand. In three days of shooting with these clucks, he missed often, experienced misfires and hang-fires of 15 seconds “or more” and had shot bounce off well-hit quail. Just as transparently fictitious is the missive of one contributor’s encounter at the massive New York City Sportsman’s Expo that winter. He’d stopped at one of the booths and asked for directions to the Recreation space, whereupon he was told Recreation is a thing of the past. “That’s a magazine that is dead,” and in this way began a long tirade explaining just why. When the captive was cut loose, he noticed the booth’s “Circle P” banner.

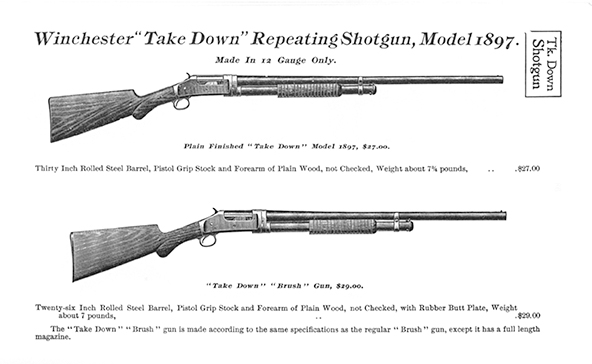

When the concept of the self-loading rifle and shotgun was being considered in 1904, sportsmen divided into two camps. The League of American Sportsman was vocal in opposition to such a device. That it would prove to be the preferred tool of the game hog was their contention. The other side was either indifferent or considered the “automatic” as a milestone in the march of progress. Winchester’s president T.G. Bennett went on record as defending the automatic shotgun in principle. Within the industry, it was no secret that the “Big Red W” had such an article already in the works, with the intention to market it.

George Shields invested the whole of page 190 in the September, 1904 issue of Recreation to present his slant on Mr. Bennett’s public addressing of the “agitation of a certain New York magazine that was put up, we think, to injure us,” and further alluded to the magazine’s call to join “a certain sportsman’s league.” Mr. Shields took up a lot of space and caustic words summarizing his response to Bennett, once a valuable advertiser as “a lot of rot.”

From the Editor’s Corner column in the same issue was another editorial not to be overlooked. To settle a bet and to prove a point of Recreation’s “world-wide reputation,” Shields had a subscriber who was living in Texas, mail an envelope addressed only to “Editor Recreation, Game Hog Dept.” After some delay and showing some handling, the envelope landed on the right desk.

In the Publisher’s Notes section of the June, 1904 issue of his magazine, Mr. Shields heads off with a “reader’s” question, which seems to bear the foul stamp of George Shields, but bears the signature of one Lester G. Miller. Lester asks, “What is the cause of the disappearance of the Winchester ads from Recreation? Did they get their back up about the criticisms of their guns in your magazine?”

According to Shields, there had been a polite squabble he’d had with Winchester’s president Bennett. Recreation’s publishing of a contributor’s letter, in which the Winchester pump shotgun was condemned by an overzealous automatic hater, and the rumors of a Winchester automatic seemed to enrage him to the point of spouting off. Another innocent offence, Shields’ use of several paragraphs to detail personal recommendation to use hand loads in modern revolver cartridges to save money, which according to the ammunition manufacturer “injured” his business, and contributed to the decision to drop Shields from its roster of advertisers.

Mr. W.T. Hornady had asked Denver-based Outdoor Life Editor, J.A, Maguire, to be allowed some space in his magazine to broadcast the recent troubles of the League of American Sportsmen. Maguire was privy to most of the publishing trade news and scuttlebutt, and knew well each of its personalities through direct dealings or by reputation. He allowed Mr. Hornady nearly two full and precious pages of the December 1904 issue of Outdoor Life for his rant that Editor Maguire “took great pleasure in publishing.”

Hornady, the “Number Two” man in the LAS and the Director of the New York Zoological Society, wanted to publicly air a grievance with the Washington state chapter of the LAS. Leaders in that group had designs to defect from the LAS to stand on their own. They had already commandeered the annual LAS National convention from the entitled chapter and relocated it to Seattle.

Hornady’s portrayal of George Shields was as a pitiable, beleaguered man who lived simply like an “impoverished hermit.” The man’s life and focus had been protective measures for America’s game. To that point in 1904, Shield’s had spent $70,000 “from his own pocket.” “The league is making Shields poor,” Hornady insisted.

Maguire then used his editorial soapbox to air his gripe with Shields, who continually professed to promote the cause of game preservation, but in 1902, he had strongly opposed the formation of a Colorado association not affiliated with his LAS. Lastly, Editor Maguire delivered his pithy sermonette about the chronic bad boy typically being blamed even when innocent of wrong-doing.

The big news in Recreation’s March, 1905 issue was this simple declarative opening sentence – “Mr. G.O. Shields is no longer connected with Recreation.” While this unexpected disclosure was sinking in, it was followed by another: “In the future the magazine will be issued under the editorship of Dan Beard.” Dan, a 55-year-old, was described as “a man of simple habits and studious nature.” He was a writer and novelist, and was of the necessary “straight-shooter” sort to replace the naughty Shields. In his future resumes, Beard would be known as the founder of the Boy Scouts of America. William A. Annis became Recreation’s publisher. Mr. Annis was an old hand in the domestic magazine business. He had been an ad man for Outing, then for Colliers before working for Success magazine. The two of them intended to run Recreation in the direction it was headed and founded. Beard’s words were, “We shall continue to wage an uncompromising fight for the protection and conservation of all game.” Recreation seemed to be left in good hands.

The obvious questions that may have been asked by long-term Recreation readers were skillfully avoided. Unanswered was the cause for Shield’s replacement, and on whose authority was this done.

Mr. Shields must have had an inkling that his days were numbered. Just prior to the “Great Undoing of 1905,” Shields hinted at a raise in subscription prices and offered this hoodwink of a reason “…I have lost the advertising of the Winchester Arms, U.M.C., Remington, Bridgeport Gun and Implement, DuPont Powder and Laflin and Rand Powder Company…by reason of my crusade against the automatic and pump gun and against the market hunters.”

The readers who were shocked by the news, and wondered about the unexplained changes, then questioned on whose authority the decision had been made. They got their answers not from Recreation but from another magazine.

J. A. McGuire updated his readers on the Recreation matter in his February 1905 issue. The New York Times had reported on January 6th, that George Shields had filed for bankruptcy, listing his only tangible assets as some furniture and “ornaments” valued at $500. The judge had noted that the subscription list, the real value of the business, could have brought $4,000 - $5,000 if sold advantageously. It followed that the judge appointed qualified people to oversee Recreation after the bankruptcy.

Editor McGuire was privy to all of the industry news and scuttlebutt. When he announced the failure of Recreation in his February of 1905 issue of the magazine, he went on to be openly critical of a fellow publisher. He pulled no punches about his assessment of his peer in the business when he wrote, “No other American sportsman’s magazine ever started out under more suspicious conditions and none has ended in such ignominious failure.” Maguire wasn’t finished with Shields just yet: “Fifteen years ago Mr. Shields stood on a pedestal of fame before the American sportsman as a hunter and writer (but unfortunately not as a game protector). Now, after many years of labor, he must swallow the bitter pill of failure. It was known generally that the magazine was not paying in the late years, for its subscription list had been gradually shrinking year by year. No publication on earth could withstand the policy which Mr. Shields had injected during the last five or so years.”

George Shields wasted no time in getting out his own competing monthly magazine, one with what he must have considered to be a still marketable name – Shields. The inaugural issue was the March 1905 issue. The cover contained a reminder that he was “formerly the editor of Recreation.”

Just as soon as he was ousted by the powers at Recreation, Mr. Shields mailed a circular letter, bearing the header: “What does the Old Guard say?” to everyone on Recreation’s subscriber’s roster, offering a four-year subscription to the new Shields for $5. There were a lot of takers. One published response, accompanied by a check, is located in the Volume No. 1, No. 2 (April,1905) issue of Shields is evidently representative: “Your circular just reached me. This is the time when you will find out who stands by you. I am sorry I couldn’t make it more, you have done great work and are needed.”

Shields took the LAS with him, and seemed particularly eager to use it to secure more funds. He used a full page of his new magazine to issue an appeal that some might have seen as frantic and belittling. “I have spent more than $15,000 of my own money in this work, then why should not YOU spend a dollar a year of your own money to help the cause? If you have any good reason for staying out, will you please tell me what it is?” he yelled unnecessarily in large type. The noticeable number of display ads from long-term advertisers in the first issues demonstrates that the man still had some appeal.

Since being ejected from his position with Recreation, Mr. Shields had been industriously circulating false and malicious statements against the magazine. Honest, principled people in management peaceably counteracted Shield’s caustic tactics by doing nothing, allowing his rants and giving a man headed for the proverbial gallows ample rope. Shields had spent some time in bankruptcy court. According to creditors, who claimed that the man filing bankruptcy neglected to schedule – and had purposefully concealed certain property and assets that were held by him. The judge making the decision was presented ample evidence and proof, and agreed with the creditors. The court used the adverbs “knowingly, fraudulently, and intentionally” to describe the man’s misdeeds.

The second part of the Recreation editorial was the reprinting of a letter sent to Shields by President Theodore Roosevelt, and was also published in the New York Times on March 30, 1906. Shields had called on the president informally and the two talked of the preservation of game and wild things and wild places generally. Shields was trying to get big name backing for a piece of legislation. Roosevelt had cautioned Shields that he wasn’t to be quoted, and followed the verbal caution with a letter containing the same emphasis. Shields weasel-worded the President’s statements until they fit what Mr. Shields would have them mean.

The President learned what had been done. He sent a scathing letter to Shields and a copy to the New York Times for publication. It scorched the pages of the Times on March 30, 1906. Teddy’s letter to Shields – and the Times, closed with Roosevelt’s unsparing rebuke, “But when you attempt to give my exact words, you not only do what I explicitly told you that you should not do, but you used language which I explicitly told you was in no case accurate. Not a single sentence you quote is as I said it. Some of the sentences are sheer inventions, others are inventions in part, and some of the things I said are omitted. It is unnecessary to characterize such conduct on your part. Yours etc., Theodore Roosevelt”.

By 1912, George Shields had run out of advertisers to offend and his full quota of readers to alienate. He’d exhausted what was once thought to be an unlimited supply of pitches, and was fresh out of favors to call in. He was out of things to print and the readers to read it. Shields magazine ceased publication in August of 1912, and George Shields himself died in 1925.