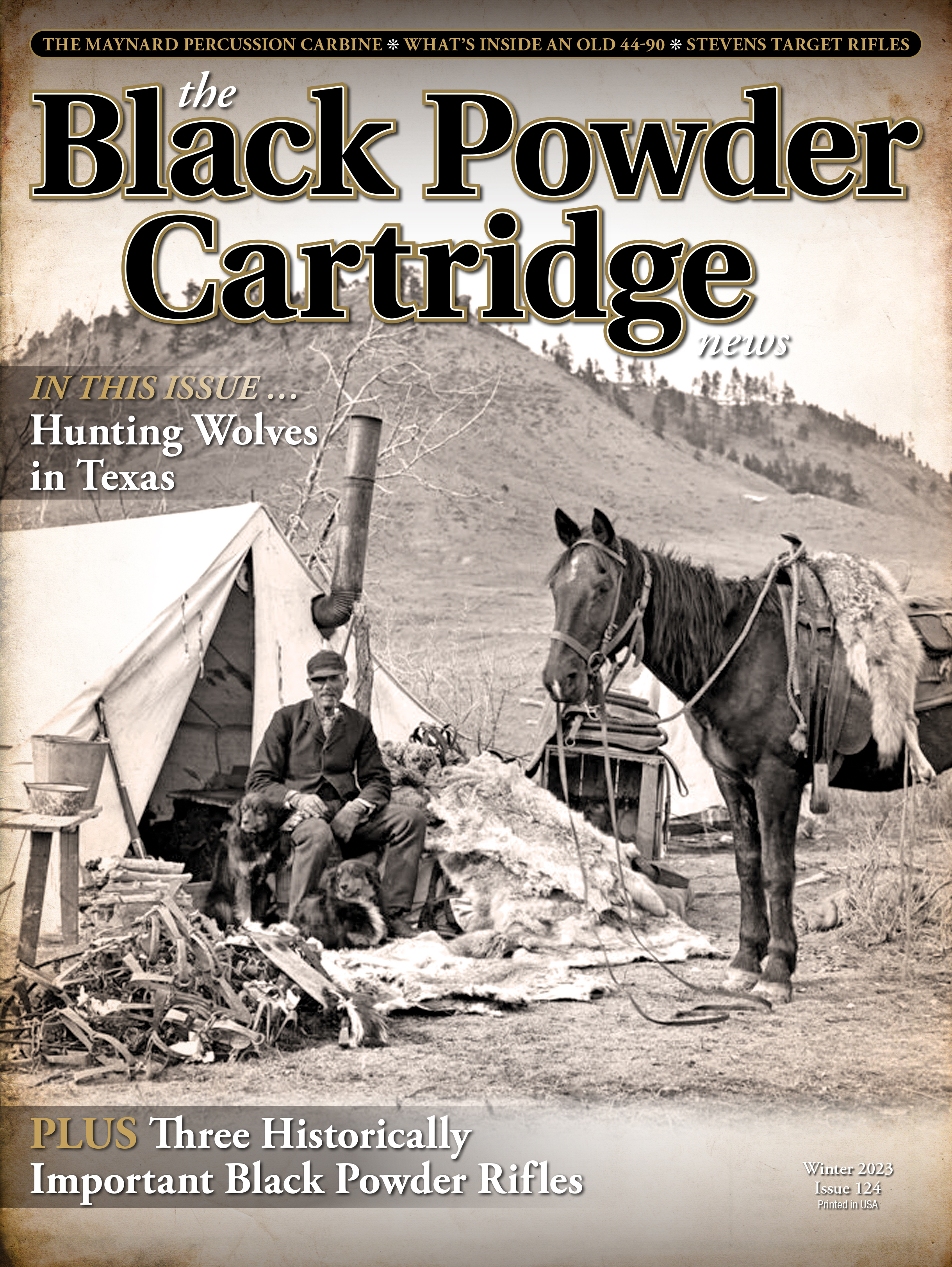

James Graham – Hunting Wolves in Texas

feature By: Leo J. Remiger | December, 23

The following account of James Graham is from an interview conducted by a reporter from the Emporia Ledger,1 Emporia, Kansas in 1878. The interview was conducted when Graham was passing through that area. It is so interesting and written in the language of the time and place that we have decided to make very few changes. We only wish the reporter had identified himself so we could credit the article to him. We do not know what changes he made to James Graham’s narrative or if he put the story down on paper exactly as James Graham dictated – but it’s a wonderful story of just some of the experiences of a trapper and wolfer on the frontier in those days.

James Graham – Hunting Wolves in Texas

“James Graham, an old Texan hunter and trapper, provides some interesting particulars of life on the buffalo range. The professional wolf hunters operated on the great hunting grounds comprising the area which were watered by the Red River, the big Wichita, Brazos, Colorado, Concho, and Pecos. The highest grade of hides, technically termed “Southern fur,” brought $1.75 apiece. Skins taken north of the Arkansas were more valuable, because the fur was finer and thicker. The wolf pelts were classed as follows:

No. 4 More Hair than Fur

“The price varied from $1.25 up, according to the quality. The animals were killed between the 1st of November and up until the middle of February. After that, their coats became thinner and they began to shed their hair, so that the skins were worthless. Further North the season lasts much longer. The coyotes were hunted with the big gray wolf, but their hides, being much smaller, brought only $.75.

“Graham mentions a man named Bell who operated out of Fort Griffin and is credited with killing more wolves than any one man on the plains of the Arkansas. In one season he poisoned over 500. From three to four good hunters used to club together and hunt this season through.

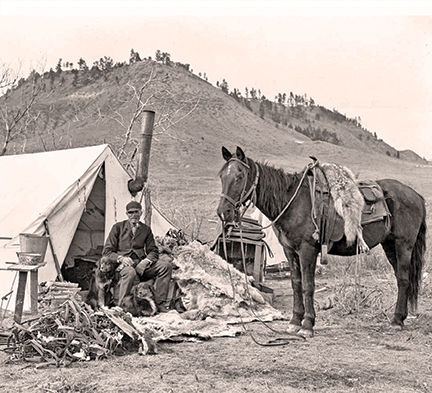

They started out with a wagon well loaded with flour, bacon, sugar, salt, and coffee. An extra pony or two came handy to ride around, keep the baits in order, and bring in the hides. The trappers carried plenty of ammunition, and when using breech loading rifles, filled their own shells. As the Comanche were trouble-some, the rifles were loaded and the horses strictly guarded. At night they were hobbled in the brush near the camp, so that they could not go astray. If the “sign” was good, camp was easily made in a secluded spot near a running stream, tributary to one of the large rivers. As the wolves followed the buffalo, and the buffalo cropped the juicy grass along the streams, the “sign” was always good in a wild and well watered section of country. By the sign which consisted of the tracks and half eaten dead buffalo, the trappers estimated the number of wolves, and prepared their baits. Buffalo, antelope, or deer, were killed in an open place, and strychnine placed in those portions of the carcass first torn by the wolves. The trappers, as a rule, did not plant the poison before sunset, for the wolves of the air, the innumerable ravens that shadow the plains and feed upon dead animals, displaced the baits if the traps were set before they went to roost. Often the ground near the carcass was sometimes sprinkled with dead ravens. Small flocks staggered around the dead bulls under the influence of the poison, and gyrated through the air like tumbler pigeons.

“The colder the weather - the more wolves. A nipping, frosty air seemed to sharpen their appetites, and give them a keen scent. While Graham was on the Brazos, five winters ago, eight bison were killed on the side of the hill, and their bodies skinned and poisoned. During the night the wind veered to the north, and the weather became intensely cold. A storm of sleet made the campfire hiss, and the howls of the wolves ring above the ravine in which the hunters slept. With the first break of daylight they visited their baits, fearful that the ravens might tear the fur of the dead wolves and damage the hides. Within three hours they found the bodies of 56 large gray wolves frozen so hard that they dragged them into the ravine and thawed them out. All agreed that if the night had been mild the animals would have kept undercover.

“A wolf begins to feel the effect of the poison within ten minutes. He stops eating. His ears and eyebrows twitched, and his limbs are cramped. Frequently he whirls around like a dancing dervish, sweeping the ground with his tail and throwing up the dirt with his fore paws. His comrades cocked their heads to one side and watch his spasms with curious eyes, but resumed their feast when the victim stiffens or starts for the scrub. Few of the poisoned animals died at the side of the poisoned buffalo. Old hunters assert that the strychnine produces a burning thirst, and the wolf makes for the nearest water. This keeps the band of trappers busy all morning. While two of them skin the wolves nearest the baits, the other mounts a mustang and scours the chaparral and banks of the river in a further search for bodies. The ravens assist him, filling the air with wild cries, and fluttering over the gasping animals in the brush. Many of the wolves are not dead when discovered. They are scattered about in all stages of paralysis, and are put out of their misery by the hunter. Occasionally a dying wolf is found stretched on the sands of the river lapping the water, but he does not rush into the stream, and his body is never found floating upon its surface. Even in death he seems to have a horror for wetting his feet.

“The only wolfers adept at skinning are the professional hunters. The body is turned upon its back and work begins at the forequarters. The trapper grips a leg between his knees, opens up the hide to the brisket, and rips down to the tail. The tail is the most valuable part of the wolf. If injured, it spoils the beauty of the robe. It is therefore taken off with the greatest care. The skinner than plants his foot firmly upon the neck, and by main strength peals the hide up to the head. Here more care is required. The ears and nose are torn away with the skin, so that spread upon the prairie it presents a perfect picture. The hide is then folded flesh side in, thrown across the back of a pony and borne to camp. The fur is then turned to the grass and the skin stretched by pegs driven into the ground. It dries according to the weather. No salt is used. If the atmosphere is dry it is taken up within three days, and turned over and sunned until ready for market.

“While the trapper is thus picking up the skins of the big gray wolf he does not neglect the coyote. This is much smaller than his gray brother. The latter is nearly as large as a Newfoundland dog; the former about twice the size of a cat. The coyote fancies a campfire, and sits on hillocks with in sight of its blaze barking for hours. The gray wolf bays at the moon like a dog. Graham says he has seen them sitting on the highest rocks gazing at its bright orb with their heads thrown back uttering unearthly howls. The wolf scorns the coyote. When the large wolves drag down an old buffalo bull the coyotes huddle in the vicinity, licking their chops and barking, as though begging a share of the prey. Should they venture too near the big fellows utter ominous growls and the coyotes slink away, tails between their legs and heads turned over their shoulders. The coyote quickly determines the status of the hunter. If he finds him killing wolves he keeps a respectful distance; but if he is only hunting bear, antelope or buffalo, the little fellow becomes quite social. While a bear hunter was butchering game, coyotes patiently watched his operations, and the gray wolf loped hungrily on an outer circle. The trapper threw a piece of meat to the small fellows, who ran off and were waylaid by the big wolf. They dropped the meat and returned, but seem to learn nothing by experience, for they fed the robber as long as the hunter chucked them the meat.

“Many coyotes pick up their supplies in the prairie-dog colonies. If one is lurking in the streets and sees a dog away from his hole, he steals upon him with the utmost secrecy, striving to cut off his retreat. As an old dog, however, is rarely caught napping. Some of the fraternity are sure to espy the wolf, and a warning bark sends the dog into his hole with the tantalizing shake of the tail. The coyote despondently peers into the hole, rakes away the dirt with a paw, and sniffs at the lost meal. He gets his eye on another dog, and crawls toward the hole like a cat upon a mouse. The warning bark is again heard, and a second meal disappears. Infuriated by his disappointment, the wolf frequently turns upon the little sentry, and for a few seconds makes the sand fly from the entrance of his readiness. Worn out by his futile efforts, he flattens himself upon the sand behind the hole, and, motionless as a statue, watches it for hours. If the dog pops out his head he is gone. The wolf springs upon him, and jaws come together like a snap of the trap, and the helpless little dog is turned into a succulent supper. One Metley, a well-known buffalo hunter, was riding across a dog town some years ago when he saw what he supposed to be a dead coyote stretched out at one of the holes. He dismounted and lifted it by the tail, intending to take the body to camp and skin it. The coyote made a snap at his leg, wriggled from his grasp, and sped over the prairie more surprised than the trapper. He was in a sound sleep when caught. But the coyotes greatest harvest is in the spring of the year, when they fat themselves at the expense of inexperienced young dogs caught wandering from home. Whole families enjoying the cool evening breeze on the mounds above their burrows are taken unawares, and the tender young snapped up before their parents can force them under the ground.

“The wolf follows the buffalo and is ever skirmishing on the edge of the herd. Indefatigable in the chase, he pursues his prey for days without sleep. He catches his naps in the sunlight, and does the bulk of his work at night. He never declines an invitation to dinner. A great glutton, he stuffs himself till his paunch is distended like a bladder, and in this condition is often run down and lassoed by the cowboys on ordinary ponies. Some of the Southern tribes never slay a wolf. They have a superstition that when they die their spirits roam the prairies in the guise of wolves. “Who say a wolf may slay his brother?” is an old Southern plains proverb.

“Cruel and voracious, the gray wolf is an arrant coward. While on the Brazos in 1873, and camped above what is called “The Round Timbers,” Graham killed five buffalo for bait. He charged three with strychnine, and in the morning found five dead wolves. Three great eagles were perched upon the head and shoulders of an un-poisoned carcass, and two large gray wolves were tearing the hams. The eagles regarded the wolves with an evil eye. At intervals the most powerful bird strode over the carcass with outstretched wings and open beak. In an instant the wolves cringed to the ground, and slunk away with their heads over their shoulders like whipped curs. With the hair of their necks on end they furtively watched the lordly bird until he returned to his comrades. Then, with averted eyes, they sneaked back to the feast, and crunched and gnawed until their rapacity again excited the ire of the feathered nobleman at the head of the table.

“A striking peculiarity of the wolf is his habit of running with his head over his shoulders. Suddenly frightened, he rushes off like the wind, with his face turned back to the foe and his tail between his legs. “He ran like a scared wolf,” is a Texan’s estimate of the speed of a coward. No dog but thoroughbred greyhounds can overtake him. It seems almost impossible for a wolf to look any thing in the face. He will hardly meet the stare of a grasshopper. Graham declares that when wolves have been paralyzed by strychnine he has held them by the ears, turned their faces around, and tried to force them to look into his eyes. Not for a second was he successful. They would look over his shoulders or turn their eyes in any direction, and even entirely close them before they would meet his gaze. A story is told of a Texas farmer who caught a coyote cub, and stared into its eyes until the cub died.

“The report of a gun, said old timers, never failed to put every wolf within hearing on the alert. He immediately began to look for dead buffalo, and generally managed to secure his share of the booty. In the spring, when the calves ran with the herds, and the droves were resting at noon, the big gray wolves organized for an attack. Woe betided the calf on the outskirts of the drove. The ferocious beast would cut it out in a rush, after stampeding the herd. If the calf was nearly full-grown they would ham-string it with their teeth, but if young and tender would tear out the throat before the dam could come to its defense. Frequently a lone wolf routed out an old bull, driven from the herd by younger and more active bulls. He caught him by the nose, and hung on until shaken off. The attack was kept up until the bull started on a run. The wolf kept in the rear until the old patriarch showed signs of fatigue, when he resumed the attack in front. The buffalo was not allowed to lag. If he fell into a walk he was again seized by the nose. When nearly exhausted the howls of the wolf drew other wolves from their lairs, and between them the old veteran was ham-strung and rendered helpless, and finally torn in pieces by the pack.

“Gray is the common color of the wolves in Texas. Occasionally white ones are killed. Graham says that he killed eight in one winter with skins as white as the driven snow. The black wolf is very scarce, and mostly found in the timber. His fur brings the highest price; but, during six years of trapping, Graham declares that he never saw one, and heard of not more than two or three shot on the Clear Fork of the Trinity by a party of Rangers.”

Thus, ended James Graham’s interview. I have omitted some derogatory comments but otherwise did very little editing. We hope you enjoy it as much as we did the first time we read it.

References:

1. The Emporia Ledger, Emporia, Kansas, 13 June, 1878.