The Ideal Match

feature By: Jim Foral | May, 20

With plenty of notice, the Second Annual Matches were scheduled to be shot at Fort Riley, Kansas. It must have been obvious that while Fort Riley was a geographically central location, it was prohibitively distant from the population centers on the coasts to draw an abundance of competing teams. Attendance at the Fort Riley meet was as disappointing as it was predictable. Only 14 teams posted at Riley.

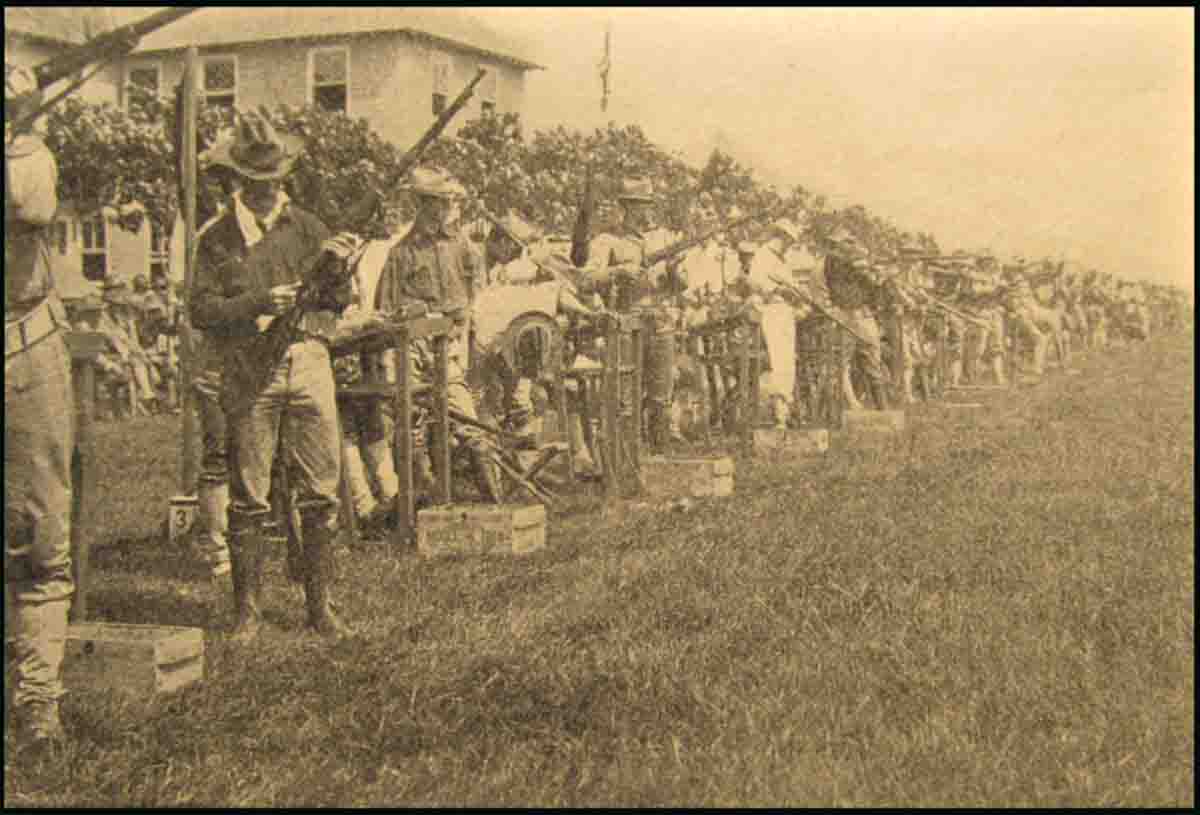

When the matches were moved to the range at Sea Girt for the August 1905 events, the number of competitors overtaxed the range facilities by three times; 650 shooters stood in line to fire the 200-yard National Individual Match alone. In 1904, there were 36 contenders for the National Invitational Match; 657 entries in 1905.

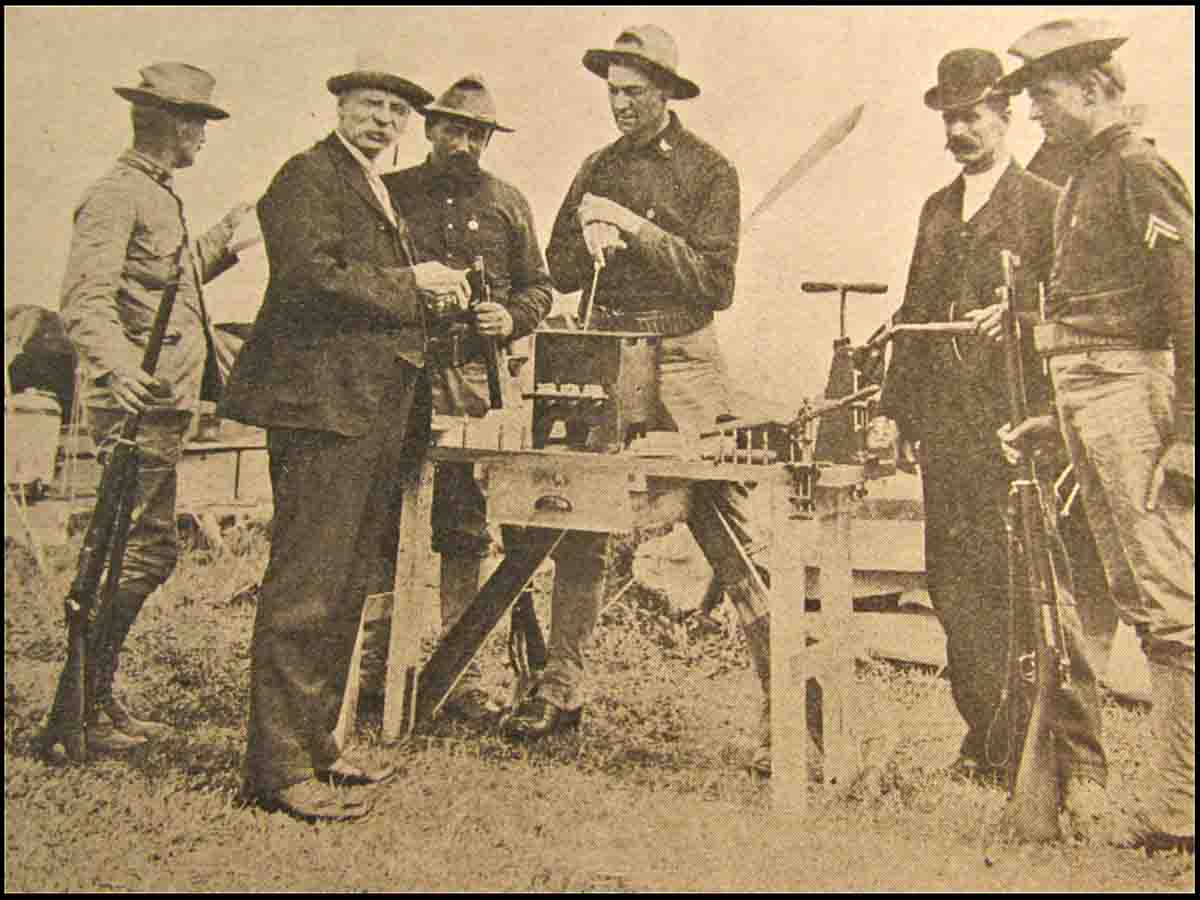

John Barlow, representing his Ideal Manufacturing Company in New Haven, Connecticut, was at the Fort Riley meet as an observer, a student and merchandiser. He was well aware of his status as an industry personality, and as a generous, likeable man with an innate flair for making friends. The affable Barlow was respectfully known within the trade as “The Ideal Man.”

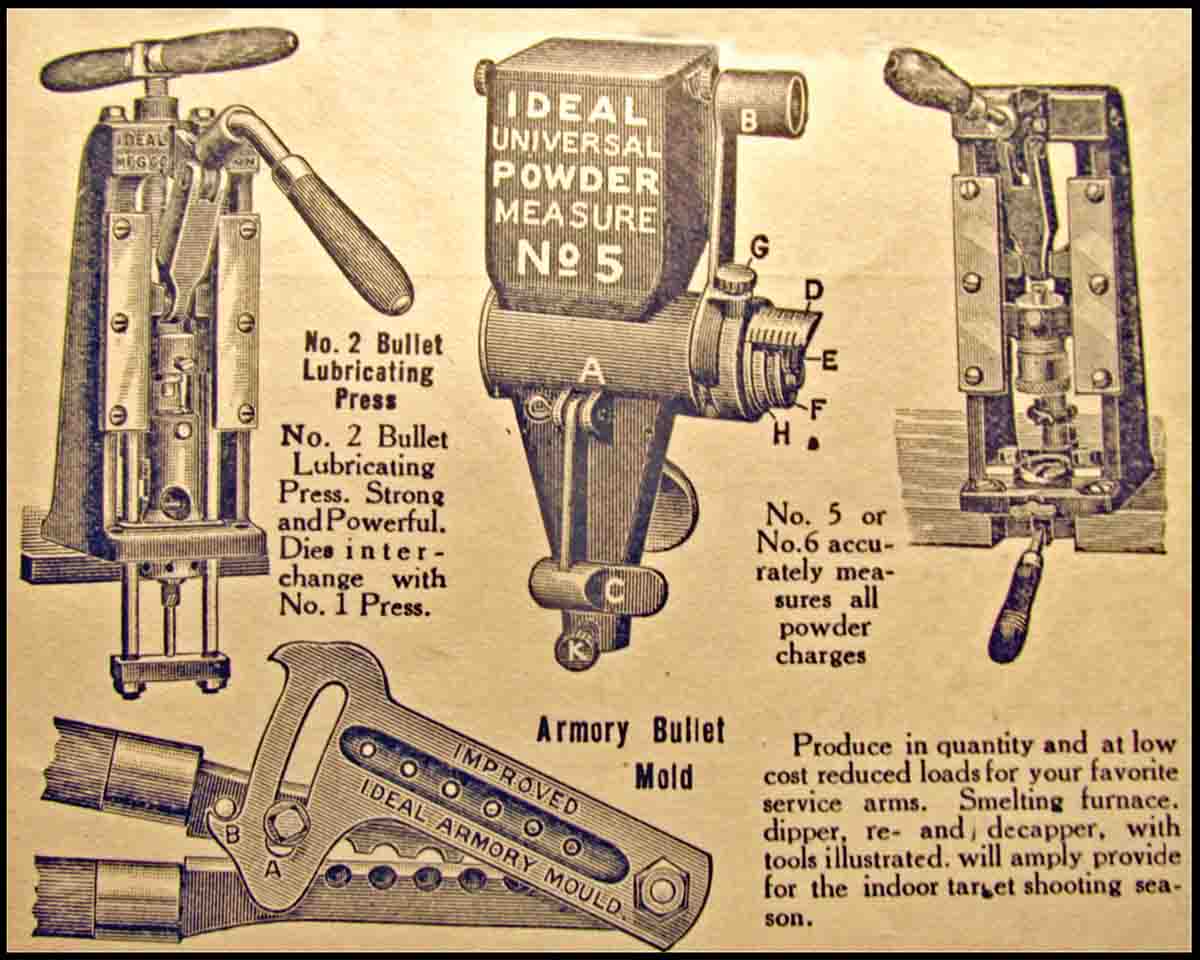

Barlow had set up a booth on the sidelines, and he and his assistants spent the entire 11-day stretch of the matches displaying his line of reloading tools to a steady stream of visitors, meeting his repeat mail order customers and acquainting with potential regulars. His Ideal “Armory” outfit, on the market for just a year, consisted of a heavy-duty press with full-length sizing capability, a gas-fired smelting furnace, an eight-cavity bullet mould and a powder measure.

This grouping of implements was directed at the National Guard units that had high volume practice ammunition requirements that his regular tong tools could not handle. Barlow and his crew were kept busy demonstrating the goods and encouraging hands-on operation of each step of the reloading process. They passed out the newly printed 32-page booklet of instructions for loading .30-40 Krag cartridges.

It seems that during Barlow’s attendance at the Fort Riley match, that the germ of an idea for an exclusively cast bullet rifle match occurred to him and developed with increased consideration. Canvassing input from intimates and the common shooters themselves, he made a plan to go forward with the idea. Also, the rumor that Winchester desired to initiate a competition similar to the Kuzer Match, as a quasi-promotional venture may have bolstered Barlow’s confidence in his plan.

It had been common knowledge that the New England National Guard units were using the industrial strength Ideal “Armory” press, moulds and tooling to load practice ammunition on a wholesale level, and these were the same units that invariably headed the winner’s lists at the bigger National Guard shoots. The Army doled out practice ammunition very miserly. Implementing Barlow’s notion could illuminate a solution to overcoming the “practice cartridge” shortage, and encourage industrious practice shooting.

To sell his idea, Barlow was at the right place and was surrounded by the most influential military officers in their jurisdictions. Each one was familiar with him by reputation and with his work in promoting economical rifle “practice” shooting by way of reloading. Barlow went home confident that ultimately such a match as he proposed would be on next year’s program.

John Barlow was successfully persuasive, and his proposed cast bullet competition was fired at the Sea Girt matches in the late summer of 1905. The inaugural Ideal Match was set up as a company team match open to all military personnel. Each trooper was permitted two sighting shots before engaging the 500- and 600-yard targets with 10 shots each. Having a two-range match followed Barlow’s intention to economize time, thus accommodating all that might want to compete. Too, he could better prove cast bullet capabilities past the short ranges.

Officially, Ideal Match ammunition was restricted to “reloaded ammunition containing a cast bullet.” There was no restriction of weight of bullet or load, but a record of components needed to be filed with the statistical officer. Barlow had brought along a goodly supply of his staff’s handloads for the free use of the masses arriving unprepared or unaware of the opportunity.

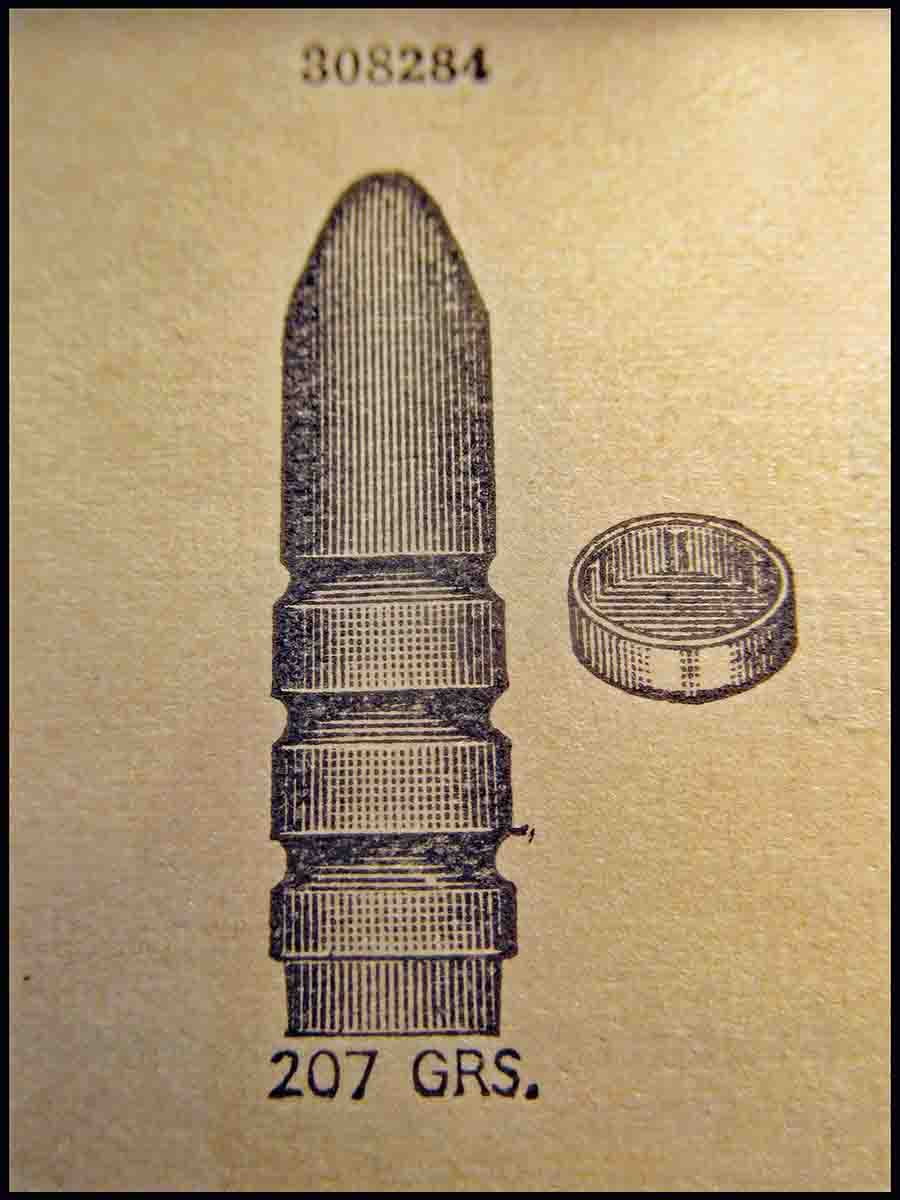

The first Ideal Match was won by the team of Company F, Fifth Maryland Infantry. The team score was 389 points. While not remarkable shooting, it was certainly credible considering the disagreeable wind and changing light conditions. “F” Company’s high man was Corporal J.R. Plumley with 84X100. The team used Ideal’s newest gas-checked bullet #308284 over 23 grains of Du Pont Lightning smokeless, which exited the muzzle at 1,500 feet per second.

Walter Hudson was pleased with the success of Ideal #308284. In many ways, he was responsible for it. From 1901-1904, Hudson had conducted an extensive series of experiments to perfect a cast bullet for affordable .30-40 Krag rifle practice. He struggled through persistently bad grouping combined with too little velocity and plagued by gas cutting and bullet base fusion. Oversized front bands and overly long base bands had failed to firewall the powder gases, and rock hard lead/antimony alloys weren’t the solution either. Hudson designed many bullets incorporating features intended to overcome each new cause of failure.

Barlow’s venture to prove his point was not a gamble of calculated risk; it was a sure thing. Later that year, the secretary of the National Rifle Association wrote officially: “During the late tournament at Sea Girt, the Ideal Manufacturing Co. of New Haven demonstrated the fact that a lead bullet having a copper gas check on its base and a reduced charge of powder, is as accurate as the full-service cartridge up to 600 yards.” While still on the record, he noted three other considerations. This type of load could be used on ranges unsafe for metal-jacketed full power ammunition. It also effectively halved the cost of cartridges and prolonged the life of a rifle barrel.

Another minor match was also on the dance card for the 1905 National Match competitor. The Kuzer Match; a timed, 30 second, rapid fire, 200-yard, five-shot affair, was instituted in honor of Col. A. R. Kuzer, a New Jersey businessman, philanthropist and ardent rifleman. This match was first contested at the inaugural National Matches in 1903 and won, curiously, by his twin brother John. L. Kuzer. J. L. Kuzer, remarkably, repeated the feat in 1904. More suspicious than curious, the winner of the 1905 Kuzer match was Winchester’s crack shot Albert Laudensack and Harry Pope finished third.

The 1906 Matches at Sea Girt were held August 27 through September 6. The .30-40 Krag still served as the official service rifle and was thus used in all military competitions. The unexpected great multitudes of shooters who showed up overwhelmed the range facilities and created tremendous troubles. On the whole, the weather refused to cooperate. The storms and fog that prevailed delayed or interrupted matches. Intermittent downpours of rain made for miserable shooting conditions and wet bivouacking. Horrendously high winds and poor light confounded reading conditions and making allowances for holding, this obviously affecting the scores. As a result, many matches were cancelled altogether. The 1,000-yard leg of the important President’s Match could not be fired at all.

Still, time was found to shoot Winchester’s match. To supplant the Kuzer match, Winchester’s ad men dreamed up and instituted the Individual 300-yard Rapid Fire Match for the 1906 program. The rules were simple enough. In a one minute time limit, the competitor rattled off as many shots as possible at the 300-yard target. The prize, only kept when the first-place finisher had won the match in three years, was a bronze sculpture famously known as “The Last Drop,” which depicted a thirsty cavalryman emptying his canteen into his hat to water his horse. The trophy, emblazoned “Winchester” on its base, was sculpted by Charles Schreyvogel, and was said to have been valued at $250.

The match drew quite the gathering of spectators and some of them used the opportunity to shoot the newest Winchester rifles. Representatives of the “Big Red W” staffed the event and were attractions themselves. It naturally followed that professional shooters Adolph Topperwein and John Boa officially finished first and second on the winner’s list. Winchester’s men, Albert Laudensack and D. McIntyre came in third and fifth. Overriding the Kuzer Match and having it won by its own hand-picked competitor was Winchester’s scheme to present to the world their new Model 1905 Self Loaders in .351 and .32 SL caliber. This was easily seen by the dullest of simpletons. Presumably, Winchester provided “loaner” rifles and ammunition to those who wanted to try Winchester’s latest system.

The instantly secondary Kuzer match (the 200-yard, 15-second time limit match) now open to any semiautomatic rifle, was won by Winchester’s Captain Laudensack. Walter Hudson fired the match with the brand-new Remington autoloader in .35 Remington.

For the entire duration of the 1906 National Matches, Barlow was a continual and conspicuous presence on the range and its grounds. When the daylight faded, he kept himself just as busy. Not by accident, he tented with good company; Walter Hudson and John Taylor Humphrey (editor of Shooting and Fishing magazine) were his bunkmates.

Sea Girt was the grand gathering center for like-minded riflemen, and at night many of them visited the celebrity quarters. Their tent was crowded every evening until midnight. Barlow and Hudson, in particular, had an interest in the absence of uniformity in .30-40 Krag rifle bore dimensions. A steady stream of guardsmen, who had spent their day shooting and shivering in the rain waiting to shoot, brought in their issue arm to be gauged. Barlow, together with Dr. Hudson, slugged upwards of 300 Krag barrels and found them ranging from .305 to .3135. The “Ideal Man” continually sermonized that a cast bullet, properly sized, would fit nearly all.

Originally scheduled for Thursday, August 30, the Ideal Match was postponed from day to day on account of the weather-caused delay of the other matches. On September 2, Brig. Gen. Bird Spencer, the range executive officer, declared an order that the comparatively minor Ideal Match would not be held, but offered the use of the range for that purpose any day of the following week – after everyone was heading home. The Ideal Match was not shot in 1906.

When Barlow’s hopes of further showcasing the capabilities of the Hudson-designed, gas-checked #308284 were dashed, he did the next best thing. Barlow distributed the great supply of handloaded Krag ammunition he’d brought for the cancelled event to the National Guard troops returning to their home stations. “A case to this company and a case to that, until the stockpile was gone,” he would later write. In this way, the targeted consumer could test and compare for their collective discovery and evaluation. On his way back to New Haven, Barlow might have rationalized that there was always the 1907 Matches.

Those National Matches were held at the spacious new State Range at Camp Perry, Ohio, and began August 28, 1907. The Ideal Match was reorganized as a company team match, and its course had been changed too. Barlow’s rifle match was now a three military-man event, each shooting 10 shots for record at 200 yards, from standing, kneeling or sitting. Then to the 500-yard line for 10 shots each from prone. Two sighters were allowed at this distance.

Still a cast bullet contest, the ammunition was handloaded and issued by Ideal. Each cartridge contained 23 grains of Lightning powder to launch the now familiar 207-grain #308284 Ideal bullet. The prizes, well worth winning, included $25 cash for the first place victors to divide three ways. Second place received 1,000 rounds of Ideal-loaded .30-40 cartridges. Third through seventh places got progressively lesser quantities of ammunition. Company “B” of the Minnesota National Guard carried away First Place.

The Kuzer Match was no longer known as that, it was now the Individual Rapid Fire Match. Its new course was a more exciting event, unleashing unlimited shots in 60 seconds at the 300-yard target. The trigger pull was to be no less than three pounds. Still, it was Winchester’s Match and Winchester’s winners. Cpt. Laudensack and Ad Topperwein finished first and second.

In terms of publicity, the National Matches shot at Camp Perry in August of 1908, played second fiddle to the coverage of the remarkable rifle shooting segment of the Olympic Games at Bisley, England, where the American team took home the rifle championship of the world. The major matches at Camp Perry received a modicum of printer’s ink, but the results of the lesser events were mostly passed over by the sporting press.

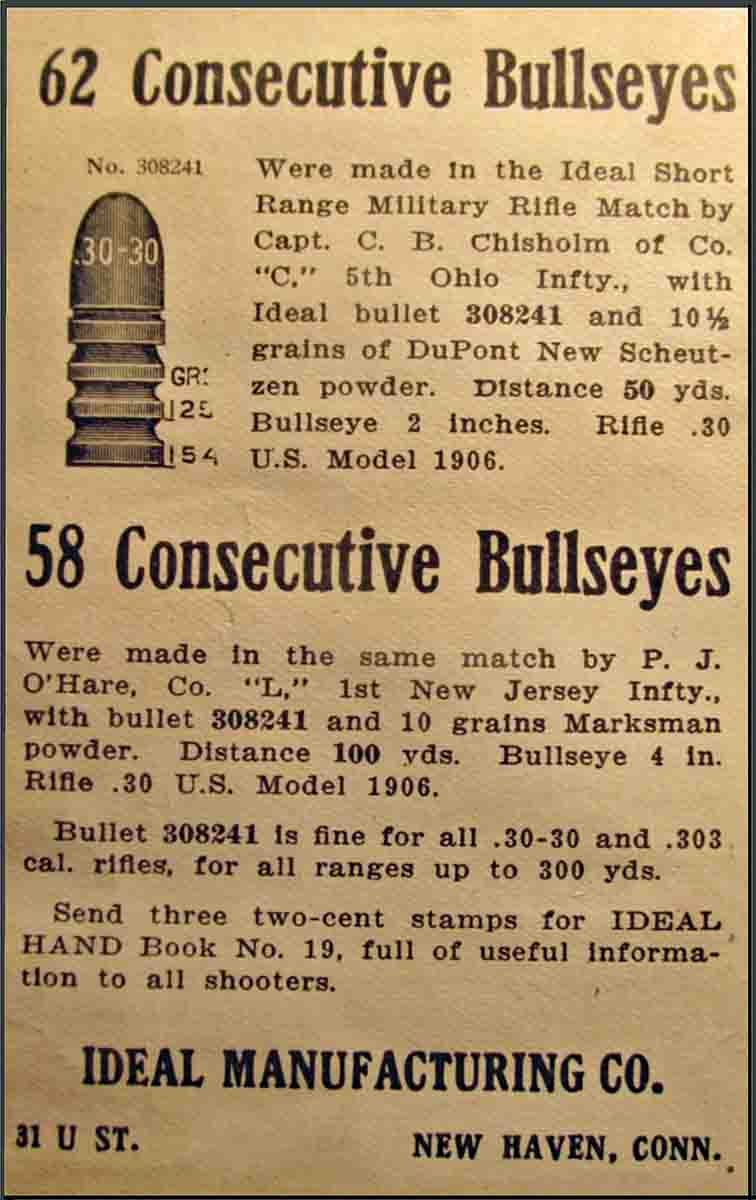

In 1908, the “New Springfield” superseded the .30-40 Krag as the official service and competition rifle. John Barlow had a stake in the public awareness that the proven Krag cast bullet principle transferred directly and appropriately to the .30 caliber Springfield. To this end, the Ideal Match transformed into the Ideal Short Range Military Rifle Match, a 50- and 100-yard event shot at a 2-inch bullseye. Capt. C.B. Chisholm of the Fifth Ohio Infantry was hard-holding enough to put through his Springfield 62 consecutive Ideal 154-grain #308241 bullets. In the 100-yard leg, P.J. O’Hare of the New Jersey National Guard shot 58 consecutive bullseyes. These results were not publicly broadcast until The Ideal Man placed ads in the commercial sections of selected outdoor magazines. Barlow had convincingly demonstrated that his system worked with both U.S. battle rifles.

Winchester Repeating Arms refused to allow their unmentioned 1908 rapid-fire match to be ignored. Again, that year, Albert Laudensack targeted 91 shots in one minute at 200 yards. He did this with his company’s model 1903 .22 Automatic Rifle and his company’s cartridges. Laudensack’s feat, a new world’s record, eventually made the papers, but only at the company’s expense.

Some things are over, some things go on. John Barlow’s Ideal Match had been successful in demonstrating the value of a cast lead bullet in a modern smokeless powder rifle and there was little point in endlessly proving it. More compelling evidence of the goal’s attainment is found in three sample testimonials found in a 1909 Ideal advertisement. B.G. Bird Spencer wrote, “Send us at once, 100,000 more of your bullets.” Thomas Reed, Ordnance Sergeant of the Connecticut National Guard expressed, “We have used 300,000 of your bullets this season in reloaded ammunition indoor and outdoor.” The Adjutant General of the same state implored, “Send us 200,000 more of your gas check bullets.”

The Ideal Match in any form was eliminated from future National Match schedules. It appears that the last year’s event with the name “Ideal” attached to it was 1908, phasing out a little known segment of rifleman’s history.

On May 16, 1910, John Barlow retired and transferred Ideal’s ownership, along with its considerable good will, to the Marlin Firearms Company. Barlow died while vacationing in Italy in March 1912. He was eulogized as “a public-spirited, large-hearted, generous man, beloved by all who knew him.”