Death of the Apache Kid

As Told by Frank Collinson

feature By: Miles Gilbert | May, 20

“I was at the WS Ranch on the San Francisco. Captain French, manager and part owner, told me that one or two Indians had been to his ranch some time before. He had a food safe hanging in a cottonwood tree. ‘It was made out of screen wire and in it we kept meat. It had been robbed, but we paid no attention.’ Shortly after this, his foreman went to the ranch to get his mail. The foreman’s outfit was camped near where the Tularosa runs into the Frisco. He left about three or four o’clock to go back to camp. The next day one of the hands came to see why he had not returned, and found him shot, not over a mile from the ranch. The hand made all possible speed to the ranch to report the killing. Captain French and a man or two went to where the foreman was lying dead. It looked as if he had been reading a letter as he rode along, for the pages of it were scattered about. His horse, saddle and Winchester were gone. The men saw moccasin tracks and knew it had been Indian work. This killing was blamed on the Apache Kid. He had not been seen for some time…

“Not long after the Kid made another raid on the Mescalero and stole another squaw. This squaw told later that the Kid had killed the first one (he had stolen) on a trip to Mexico. By then he had got to be a regular lone wolf, never stayed long in one place, but roamed about killing cattle and stealing horses. This kept up until 1906 when a sheepman was found dead in his camp, with everything gone. This was blamed on a white man who was known to be at odds with this sheepman. The white was arrested and taken to Hillsboro. He was tried, but had a hung jury, as a good many believed it was Indian work.

“The next year, 1907, the Kid stole some horses near or below Kingston, New Mexico. The ranchmen made up their minds to trail this Indian down. One party got on the trail, which led them into the Black Range. After several days, they were about to give it up when another party of men from Kingston caught up with them with fresh horses and the first went back home. The trail left the Black Range and crossed over to the San Mateo Mountains, a high rough mountain range, well covered with timber. The second evening, just about dusk, they came on some fresh horse tracks. They knew no one was in there with stock so they decided it must be their ‘long lost friend’, the Apache Kid. They hid in a draw in some heavy timber, made no fire and waited for daylight.

“The next morning, on foot, they climbed to a place where they could see all that part of the mountains. They didn’t have long to wait, for about a half-mile away they saw smoke rising out from some heavy pine timber. They started at once to surround this smoke, but kept well away until everyone should have time to take position. One man was allowed to go straight toward the smoke. He was very careful, going very slowly and keeping well in the timber. After he had gone about four or five hundred yards he came to an open glade. Here was a bunch of hobbled horses grazing. He got within 100 yards of them and squatted down by a big pine tree and waited.

“He had not waited long when one of the horses raised his head and looked his way, and there came an Indian, slipping along. He said the Indian would walk a few steps, then stop look and listen, and take a few more steps. The Indian had a Winchester on his arm, with his hand on the hammer. He walked to within 100 feet of the white man, stopped and listened again. He turned his head and looked back in the direction he had come. The white man raised his gun and shot. He said the Indian jumped right straight up and fell on his face, shot through the heart.

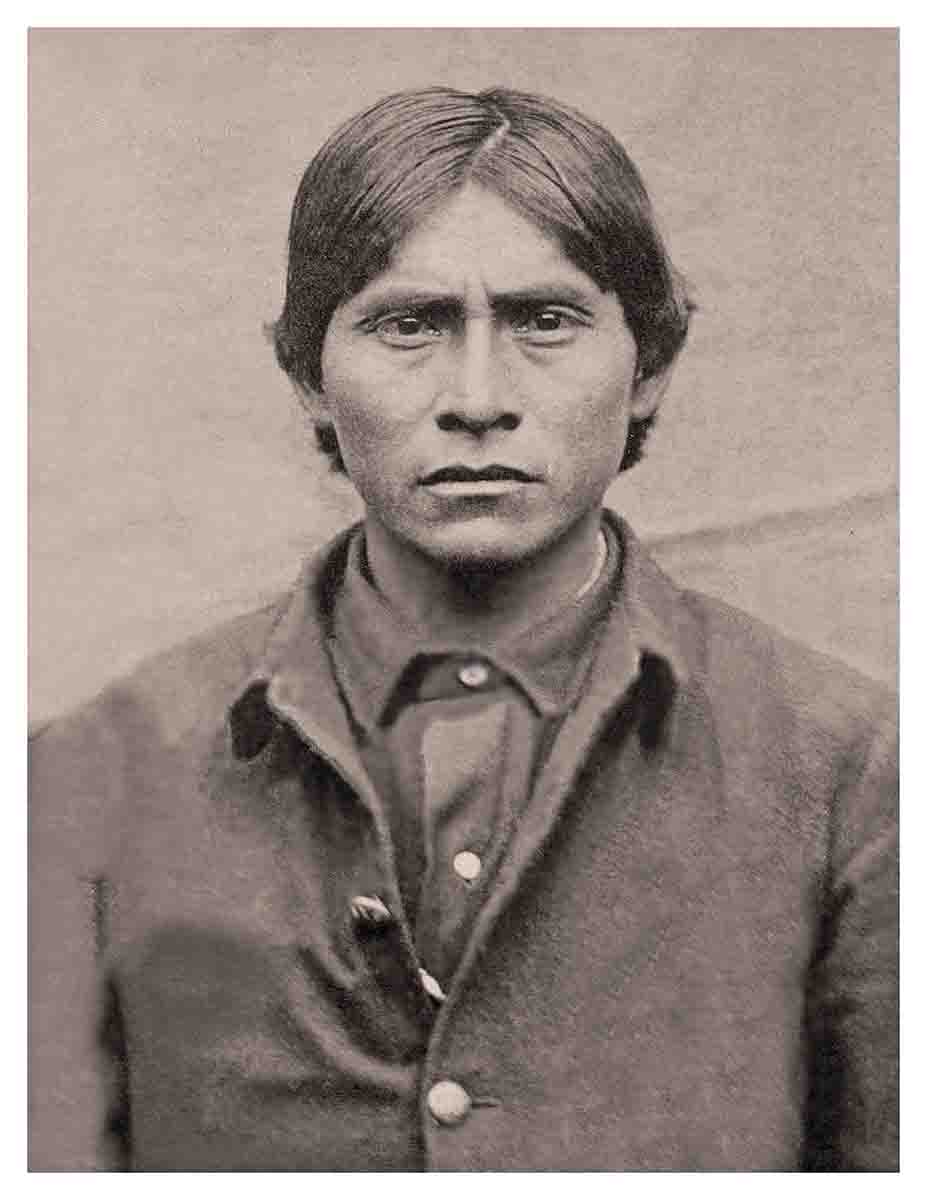

“The posseman walked up to his kill and there lay the Apache Kid, dead. Two or three of the others came on the run. They had killed another buck and had found a squaw and two children in camp. They searched the Indians and found the watch that had been taken from the sheepman, killed the year before.

“The Apache Kid was dressed like any other ranch hand except that he wore moccasins. The cowmen got a horse and dragged him to the camp, where the squaw identified him as the Apache Kid. They took whatever they wanted, his gun, a rawhide rope, hides, a few trinkets, but no money. They dragged up a lot of dead wood, oak and pine, piled it on the Kid and the other Indian and everything else they did not want, and set fire to it. When they left, there was nothing left but a few ashes.

“They gave the squaw a horse, enough bread and meat to last her and the kids to the Rio Grande, which was only an easy day’s ride. She knew how to get back to her people on the Mescalero Reservation. She left her children with a Mexican family on the Rio Grande and went on alone. She was related to one of the Mescalero scouts, an old man named Sims. He had been with the US Scouts a great many years and was drawing a pension from the government. After she returned to the reservation, Sims and another Indian went to the Rio Grande for her children. Sims also said that the Indian she had been with was the Apache Kid. He had seen the Kid on the reservation several times. Strange to relate, this old Mescalero Indian who had been in scores of fights with both reds and whites was accidentally killed in 1935 near Tularosa, New Mexico in an automobile accident.

“After the killing, the posse returned to Kingston. They had the watch and other evidence that the sheepman had who had been killed by the Kid. The case was dropped out of court and the man arrested previously was completely exonerated of the killing.

“The rawhide rope, gun and other belongings I believe can still be found in some of the homes of the families of the men who finally rid this country of the worst killer of all time.”

Endnote

Al Sieber was born February 27, 1843, in Mingolsheim, Baden, Germany, and died 63 years later in a boulder avalanche while building the Tonto Road, aka the Apache Trail, Gila County, Arizona, on February 19, 1907. In between he led a life that legends are made of.

He enlisted on March 4, 1862, in Company B, Minnesota Volunteer Infantry during the Civil War, and was severely wounded on July 2, 1863, at Cemetery Ridge during the Battle of Gettysburg. Prior to that, he had already fought in several more key engagements including the Battle of Antietam, Battle of Fredericksburg, and the Battle of Chancellorsville. He had many skirmishes during the Apache Wars under General George Crook (1862-1864), and then under Nelson Miles (1871-1892). As Chief of Scouts he was highly regarded by friend and foe alike. One San Carlos Apache renegade said of him that no matter how rough the terrain, Sieber would be sure to capture him.

On June 1, 1887, Sieber was shot and wounded in his left leg when five renegade Apache scouts, including the Apache Kid, escaped the reservation to avoid being jailed again. It happened this way: Absent from duty for five days, the Apache Kid, along with four other Apache scouts under his command, rode into the headquarters of the San Carlos Reservation. The Kid was acting chief of scouts while Al Sieber was away at Fort Apache and the White River Sub-agency.

Upon his return to San Carlos, Sieber summoned the Kid after hearing that he had killed another Apache in an alcohol-fueled family feud. Walking up to the Kid, Sieber requested that all the scouts disarm. Fearing that they will be sent to Alcatraz, the scouts resisted, with the result that Sieber was shot in his left leg below the knee with a .45-70, and fell to the ground. The renegade scouts escaped, the gunfight was over, but the long, tragic nightmare of the Apache Kid had just begun.

During his various battles and fights over the course of his life, Al Sieber received 28 wounds. According to his protégé, Tom Horn, Sieber also had 53 knife cuts on the butts and stocks of his various guns. He said that 28 of them represented those Apaches who had left their marks on him.

Al Sieber was truly one of those men whom western artist Frederic Remington characterized as “men with the bark on.” For a colorfully lurid account of the escape by the Apache Kid, see Bob Boze Bell’s article in True West magazine (May 2, 2006), titled “Tragic Powwow.” For a very credible biography of Al Sieber, read Dan L. Thrapp’s book (1995), Al Sieber, Chief of Scouts (1995) published by the University of Oklahoma Press.