A Winchester Model 64 in 32 Winchester Special shown with some 1950s cartridge boxes.

History has certainly not been kind to the 32 Winchester Special, a cartridge that was born in the early days (1902) of the smokeless powder era. Too many people have called it a “useless” cartridge, but I will venture to guess that none of those shooters who make such negative statements have had much experience with the old 32 Special. Most shooters who used the 32 Special liked it, and if they had used it as it was actually intended, they’d probably call it the most useful cartridge in what we refer to as the “30-30 class”.

Three 32 Winchester Special cartridges, a handload on the left with a 32-40 bullet.

To really understand the 32 Special, we must try to view the mindset that was in shooter’s and rifle manufacturer’s heads, back at the beginning of the 1900s. Smokeless powder cartridges were fairly bursting on the scene, beginning with the 25-35 and the 30-30, along with the 30-40 in the Highwall, and the 303 Savage in the excellent Model 99. The 33 WCF was added to the available choices for the 1886 Winchester and other cartridges were soon developed that made it look like the firearms industry was all headed in one direction, consumed by the higher velocity and energy levels made possible by the smokeless powders.

One part about shooting that was virtually left behind with those attitudes and the advancement of the smokeless cartridges was handloading. Reloading ammunition with smokeless powders was not immediately understood. Let’s face it, sometimes we still get in trouble when using smokeless powders today, especially when some smokeless powder is used in black powder cartridges and in the guns that were designed for using it. In the early part of the smokeless era, the different burning rates of smokeless powders were sometimes confusing, just like black powder is often misunderstood today. Once, when I was transferring a Sharps rifle in 50-90 to my name, I had an FFL dealer ask me, “You won’t be shooting that with black powder, will you? That stuff explodes!” It was with the 1900s handloader in mind that the 32 Winchester Special was developed and introduced; a smokeless cartridge that could easily and very appropriately be reloaded with black powder.

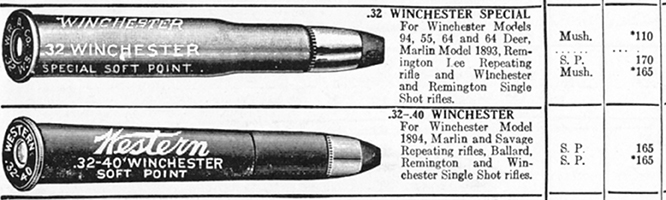

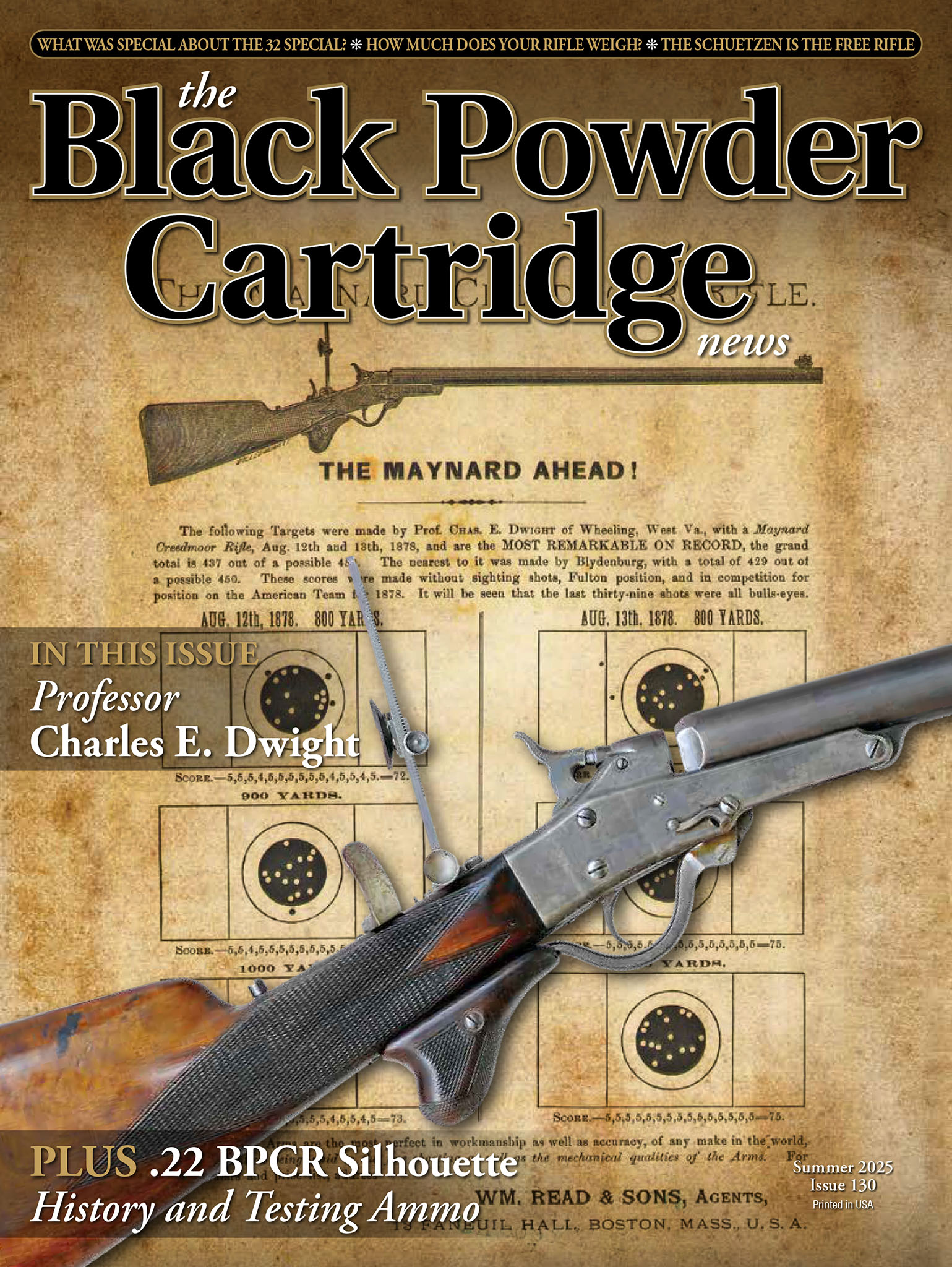

The 32 Special and 32-40 cartridges as listed in the 1939 Stoeger’s Catalog & Handbook. Note that the 32 Special was available with a 110-grain bullet. Remington listed the velocity for the 110-grain loading at 2,550 fps.

To do that, in simplified terms, Winchester took the 30-30 case and expanded the neck to accept a .321-inch diameter bullet, the same as the 32-40. The barrels had the same bore and groove diameter, plus the 1 in 16-inch rate of twist as the 32-40. With those factors in mind, we could say that the 32 Winchester Special was a black powder cartridge adapted to smokeless powder but that would not have made headlines in 1902, as much as claiming it to be a new smokeless caliber.

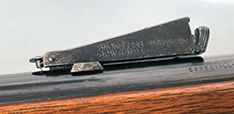

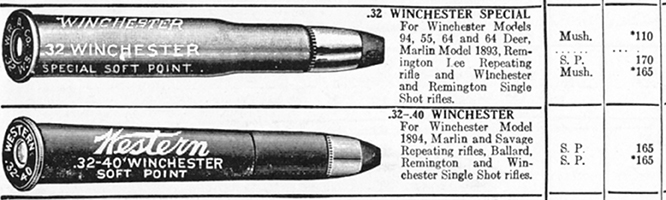

The unique 32 Winchester Special rear sight for Model 1894 rifles. Photo courtesy of Rocky Ridge Shooters Supply.

Why not just update the 32-40 with smokeless loads? That had already been done and, actually, the 32-40 had a high-power load that had a higher muzzle velocity than the 30-30 of that time. Of course, when we ask “why,” we must remember that new things, in a new “smokeless powder” era, would probably market much better than updated old-timers.

A special feature, which was available only on Model 1894 rifles in 32 Special, was a unique rear sight. This sight was marked with “SMOKELESS, 32 WS, M’94” on the left side. The right side of the sight was generally un-marked but the intention was for settings to be used with black powder, perhaps established and marked by the shooter. Many years ago, I had a ’94 rifle in 32 Winchester Special which had that sight, although, I must admit, I never put it to use back then. The picture of that unique rear sight, and the photo credit, was made available to us through the courtesy of Rocky Ridge Shooters Supply.

A shop drawing of bullet No. 32-170D, courtesy of Accurate Molds.

Another unique feature about the 32 Special was that shortly after it was introduced, factory loaded ammunition could be purchased with black powder loads and lead bullets. This was done, perhaps, with the intention of displaying the new cartridge’s adaptability for black powder reloading. Velocity-wise, the black powder 32 Special loads were identical to the black powder loads in the 32-40, which should not be any surprise. Few shooters bought the black powder factory loads for the 32 Winchester Special and those loads soon disappeared from the market.

Likewise, the promotion of the 32 Winchester Special as a cartridge that could be reloaded with black powder didn’t last very long. By 1916, in the Winchester catalog, all reference to reloading the 32 Special with black powder was missing. Instead, it was billed as a big game rifle, with more power than the 30-30, filling a gap between the 30-30 and the 30 Army (30-40 Krag). That seems to me like a way to try re-explaining the introduction of the 32 Winchester Special after the original reason had proved to be not on the popular side. Of course, by 1916, with most of the world at war, there was a lot less concern about reloading with black powder than what had been just 10 years before.

Accurate Molds’ aluminum blocks with a batch of fresh bullets for the 32.

There was one other small area where the 32 Special was unique when compared to the other cartridges available for the Model 1894 rifle. All of those other cartridges, the 25-35, 30-30, 32-40, and the 38-55 had short range loads made for them, which allowed the hunter or trapper to use the rifle for small game hunting or for the “final shot” at close range. Why the 32 Winchester Special was never given a short-range load is something I don’t understand, except that, it was billed in those early years as being a more powerful cartridge. Of course, we could easily load reduced loadings along with lighter bullets to make our own short-range loads.

Accurate Molds’ shop drawing of bullet No. 32-190D, courtesy of Accurate Molds.

During the years before World War I, the Model 1894 rifles were available in an Extra Lightweight version. The main difference between the standard weight rifles and the Extra Lightweight guns was in the diameter and the weight of the barrels. For some reason, the Extra Lightweight Model 1894 rifles were not catalogued in 32 Winchester Special caliber; they were made only for the 25-35 and 30-30 calibers. Perhaps that was a suggestion that the 32 Special was too powerful for the lightweight barrels, even though the 32 Special was available (and thankfully so) in the 1894 carbines.

In my own opinion, the 32 Winchester Special has long been favored over the 30-30, mainly because of the rate of twist in the barrels. The one-in-16 twist was, in fact, made for cast bullets. One old Lyman mould that I really like for the 32 Special is No. 321297, a bullet that will weigh about 185 grains and was designed for high power loads in the 32 Winchester Special. The bullet is heeled for a gas-check. Another bullet I have used with good success was the bullet designed for the old 32 Remington, a gas-check bullet but with a round nose design of lighter weight. While I still have those moulds, the loading done with black powder for this example, used bullets from a new Accurate Molds’ design, which is still available.

That bullet is Accurate’s No. 32-170D, a flat-nosed bullet which was actually designed for the 32-40 and it was selected for use with black powder in the 32 Special because of its plain base and the two rather generous lube grooves on its side. Yes, this bullet looks short when loaded in the 32 Special but that shouldn’t hurt anything. Most of our shooting will be with rounds loaded single shot into the chamber, but if we want to run these cartridges through the rifle’s magazine that would be no problem either.

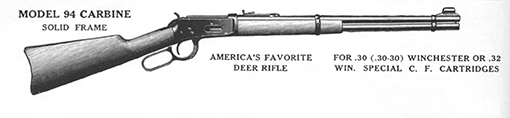

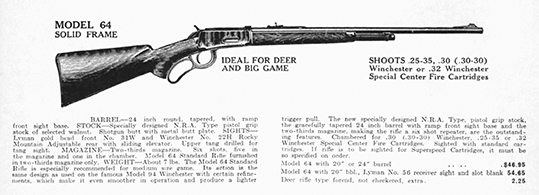

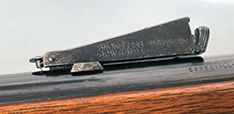

The Winchester Model 64, a fine lever action sporting rifle.

One more feature about Accurate’s No. 32-170D is the .20-wide flat point at the nose of the bullet. This could certainly add to this bullet’s game-taking qualities, should these cast bullets ever be used for hunting, big game or small. Not only would the wide, flat point punch a wider hole, but also its greater resistance would encourage more expansion as the bullet penetrated. Those are factors that help a bullet transfer its energy to the game.

Showing the caliber designation on the barrel, “32 WS,” later guns were marked as “32 Win Spec.”

If things look like more shooting will be done with black powder loads in this neck of the woods, I’ll probably be ordering another mould from Accurate, their No. 32-190D. It’s a fine-looking, plain-base bullet with generous grooves for lube. The additional 20 grains of bullet weight might certainly make a difference in penetration if it was used on game. The nose of No. 32-190D appears to have “32 Winchester Special” written all over it. If I do get one, I’ll be sure to tell you all about it, probably in a product review.

The rifle we’ll use to shoot these black-powder 32 Winchester Special loads in is a very fine gun, a 1949 graduate of Winchester, their well-balanced Model 64 with a 24-inch barrel. I selected that rifle more than a few years ago when I wanted a rifle of the 30-30 class, mainly for use with cast bullets. Until now, I had never used a 32 Special with black powder, although I do have a fair amount of experience with black powder loads in the 32-40 as well as in the 38-55. So far this Model 64 has been rather quiet, just patiently waiting its turn to speak up and be counted. A lot of my old “deer rifles” have gone down the trail but this Model 64 is certainly a keeper.

After the bullets were cast, using an unidentifiable but rather soft alloy, the reloading of the cases really brought back memories. My RCBS dies for the 32 WS are stamped with “66” for the year they were made and that’s just about the time that I bought them, brand new. Twenty-five cases were found, which I do believe was all once-fired brass, and those were quickly full-length resized because they might have been fired in a variety of different rifles. Once those cases were resized, the case mouths were chamfered, just like my father showed me how to do it, because the two-die set has no expander die. Chamfering the case mouths simply puts a little angle on the inside of the case, which makes the brass accept the cast bullets much easier and all of these were loaded without any shaving of the sides of the bullets.

With all of the cases resized and chamfered, the brass was re-primed using Winchester Large Pistol primers. Then, with the bullets, which drop from the mould with a diameter of .324 inch, going through the .321-inch sizer and lubed with BPC lube, the 170-grain bullets were loaded over 40 grains of Swiss 11⁄2Fg powder. That much powder almost fills the case, although another two grains or so could have been used. The bullets were simply seated over the powder with no wads and no compression other than from the seating of the bullets. Actually, the compression of the powder, while seating the bullets, could not be felt in the loading press handle. The bullets seated in the cases very easily. No deforming of the bullets, even though they were rather soft, was noted. The top punch inside the seating die did mark the nose of the bullet but very slightly, just enough to be seen.

After mounting the Lyman 66 receiver sight more shooting was done.

Shooting those loads came with a surprise, as their average velocity was 1499.6 feet per second. That was faster than expected because the 32-40 with the same powder charge generally gets 1440 fps. Also, the load’s performance suggests it could stand a little tweaking. While wiping the bore, which was done after every five shots, there seemed to be a bit of hard fouling just ahead of the chamber. Often, that suggests the powder is too hot, or burns too fast. In addition to that, accuracy was not as good as expected. Plans were immediately made to do more shooting, with a load fueled by 40 grains of Swiss 1Fg powder, and to have the rifle fitted with a Lyman 66 receiver sight.

The Lyman 66 was mounted to the receiver and the empties were reloaded. Those newer loads used the bullets from the same mould, no change was done there. The only difference was that for this loading, the powder was changed to 40 grains of Swiss 1Fg and the powder measure, still set for 40 grains of 11⁄2Fg, had to be opened a little more in order to get the full 40 grains of 1Fg.

A quick comment about resizing the fired cases; they were very easy to resize, as if they had hardly expanded at all. However, they did expand when fired because there was no sign of blow-back on the cases, no sign of fouling on the brass. The ease in which the fired cases went through the resizing die was simply outstanding, enough to comment on.

This five-shot group at 50 yards shows that the 32 Winchester Special knows what it’s doing with black powder.

Firing the loads with the 1Fg Swiss powder proved to be enlightening. Of course, the Lyman 66 peep sight undoubtedly helped. The rifle even sounded better while using the 1Fg powder and the last five shots fired averaged 1460 fps. That’s still faster than the same loading in the 32-40, with a similar bullet, and the bottleneck case of the 32 Special understandably produces higher pressures and slightly higher velocities. Those last five shots had an extreme spread in velocities of 25 fps. What was more rewarding than those figures, was the five-shot, 17⁄8-inch group which was shot at just 50 yards. Yes, the load using the 40 grains of Swiss 1Fg powder will be used again.

Also, the hard fouling just ahead of the chamber was not noticed after shooting the 1Fg loads. When shooting these loads, the rifle was not cleaned between the five-shot strings. Things really seemed to be on the right track with that slower powder. In addition, the 32 Special with the black powder loads was certainly a pleasure to shoot.

The 32 Winchester Special was dropped from production in the Model 94 carbine in 1973, giving it a production run of 71 years. This is a longer life than what most cartridges can claim and the 32’s longevity was certainly influenced by the guns that were made for it. Nothing has out-sold the Winchester Model 94, and it shouldn’t really be any great surprise that the 32 Winchester Special performs so well with black powder. After all, that’s exactly how it was intended. To me, perhaps just because I’m primarily a black powder shooter, that’s what makes the 32 Special “very special”