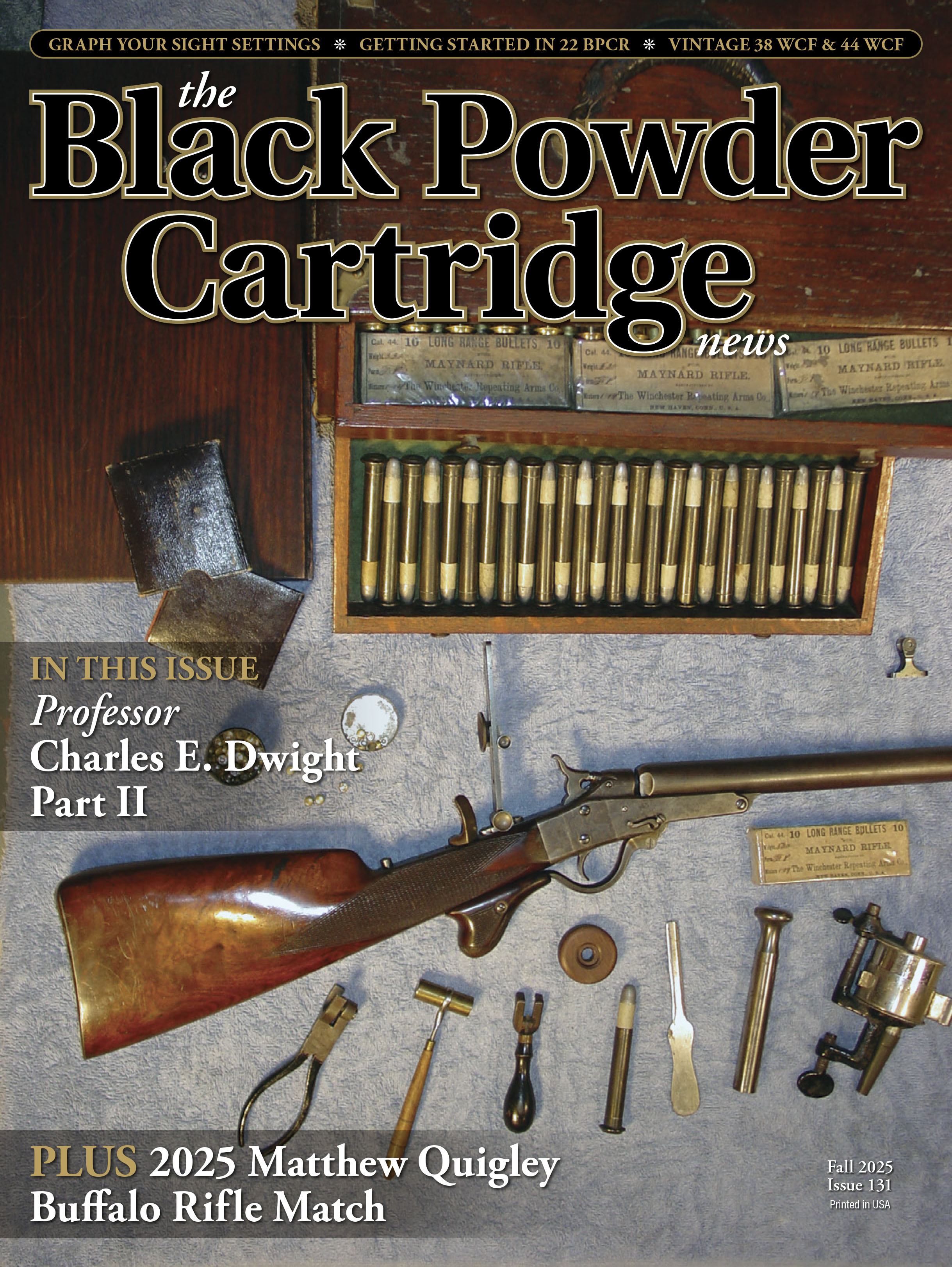

The Wyoming Schuetzen Union’s “Center Shot

The Bennett Match

feature By: Jim Foral | September, 25

Nobody in Ireland seemed to know if the United States could field a rifle team of any sort, but it was common knowledge there had been a civil war in recent years. It was also known that a general westward movement was underway, and the West’s settlement involved the killing of buffalo together with the conquest of the western wilderness and with it, its indigenous inhabitants. It seemed reasonable to conclude that Americans knew how to use guns.

The Irish club understood the daunting and uncertain task of contacting any American rifle team that might be receptive to a challenge. On behalf of his countrymen’s Rifle Association, Major Arthur Blennerhasset Leech, blindly mailed a letter containing his challenge and request for its publication to the editor of the New York Herald. The Herald, had a very limited international distribution, but in 1873, it was the only American newspaper that Leech was aware of. The New York Herald was a logical direction to point his metaphorical “shot in the dark.” As things turned out, the Irish shot into the darkness, could not have been better centered. Leech’s letter landed on just the right and most advantageous desk possible.

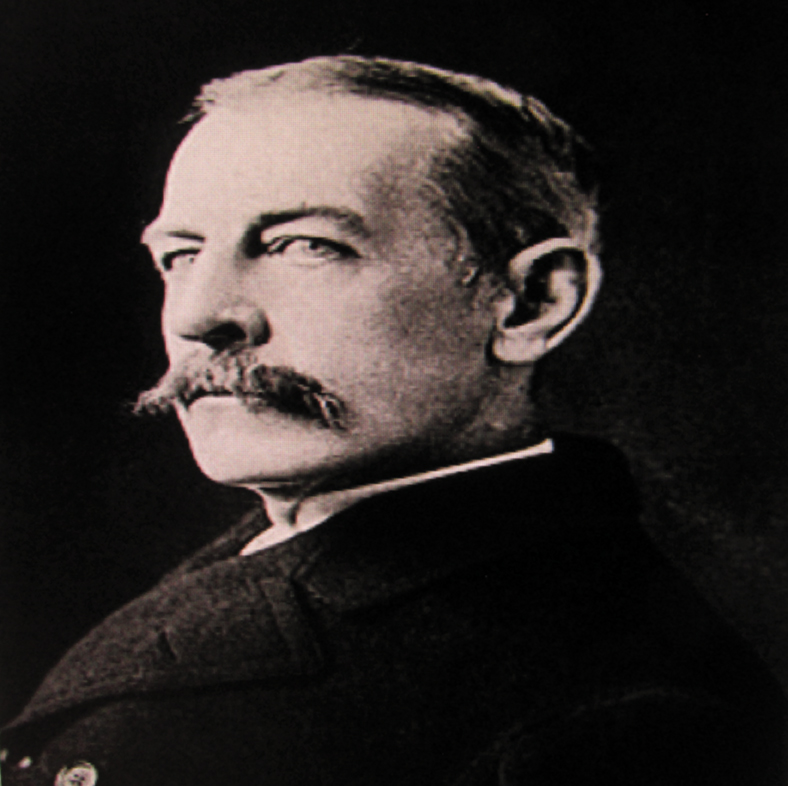

It was the 28-year-old James Gordon Bennett, Jr., who had underwritten the successful and storied hunt for David Livingston by Henry Stanley that ended on November 10, 1871. It was also he that opened the letter postmarked Dublin, Ireland.

As an open letter to an unspecified concern, the Irish challenge was printed in the Herald, as Major Leech requested. It came to the attention of the members of the freshly organized Amateur Rifle Club of Metropolitan New York City. They met and agreed to consider the formal proposal of the Irish team. The Irish invitation specified that the proposed meeting would be conducted under Elcho Shield rules for course of fire and other match guidelines. Also, alluded to was a certain willingness to vary from that rigid form to accommodate whatever variances or customs the Americans might recommend. After a bit of back-and-forth correspondence, plans for a match in September of the following year were solidified. To this point, no member of the Amateur Rifle Club had ever fired at a target farther than 800 yards and most had not faced the 500-yard mark. There would be a lot to get done in a year’s time.

Ample transoceanic communication between the two nations eliminated any foreseeable trouble that otherwise would have been a source of misunderstanding, and facilitated harmony from the start. New York officials planned a “best foot forward” welcome for the Irish guests, many of whom shared the same last name with many of New York’s more recent citizens. The non-native New Yorkers seemed fascinated with the novelty of their fellow countrymen crossing an ocean for the purpose of shooting guns.

An avid sportsman, Bennett introduced polo to the U.S. Among his many sports-related milestones was the organization of the first polo match and the first tennis match in the United States. He encouraged yachting, and later automobile racing. Mr. Bennett himself won the first trans-oceanic yacht race with the finish line 14 days into an iffy future.

He had always been particularly fond of “long-distance walking” and promoted it to a short-lived urban craze. He established the Gordon Bennett Cup for International yachting and later the same prize for automobile racing. The sport of ballooning also had a coveted prize known as the Gordon Bennett Cup.

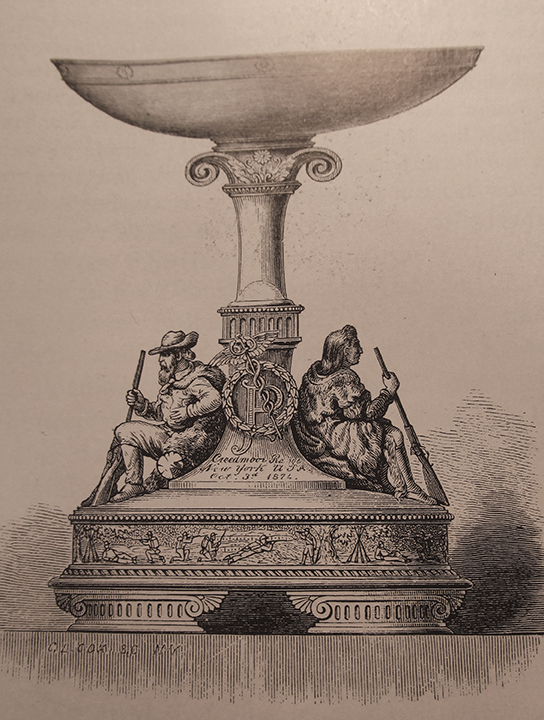

He commissioned the New York City silversmiths of Gorham Company to design and execute the opulent centerpiece that would be known as the “Bennett Cup,” which was to be first prize in the Bennett Match. It stood 18 inches high, intricately engraved and was made of solid silver. Somehow though, it was leaked to the press that its cost was $350. There is always a public interest in this sort of news.

The “greener than green” Amateur Rifle Club had been loosely organized in 1872. It’s first intra-club, 500-yard match, was conducted in July of the following year and drew but 12 entries at the Creedmoor grounds.

The team’s preparation and training effort (after its initial “blind leading the blind” process) developed into a community undertaking once a focus was seen. The fledgling National Rifle Association did their best to bring about a better and more current awareness and understanding. Allied arms industry representatives stood ready to contribute in any way to the overall effort. The tired old surplus .50 caliber Remington Rolling Blocks supplied to the eastern gun clubs by the unstinting State of New York, simply did not stand a chance as match rifles, and practice with them just reinforced already bad habits.

From several standpoints, the Sharps Rifle Company and Remington Arms, both stood to profit and gain considerable public notice and profit by providing the team’s target-worthy breechloaders. For the greater good, both firms engrossed themselves in building and providing the team with the latest and the best cartridge arms that man was capable of providing. The ammunition makers got to work determining the best combination of powder and bullet, and testing the product to faultlessness.

In the meantime, the two competing rifle teams exchanged particulars concerning match rules and allowable rifle specifications. And, as two strangers from different continents and somewhat unfamiliar with the cultures of one another, there was further communication on what to expect from one another on the range. The metropolis of New York City swept its streets in readiness and prepared a warm welcome, as well as offering to host the team and its expected entourage of dignitaries from the Emerald Isle.

For the American rifle squad, preparation was a co-operative group effort. The Americans needed to equip themselves with suitable breech-loading, match-grade rifles, which were sighted the same way. Remington Arms and the Sharps Rifle Company co-operated to send to the Creedmoor firing lines the best modern breech-loading rifles that they were able to produce. Both concerns had an awareness that a good showing at the International Match would be an advertisable point of pride for their companies. The ammunition makers got busy too, working up their cartridges to a nicety, testing and improving to faultlessness.

Not as a less consideration, the Amateur Rifle Club needed to master their rifles, sights, and ammunition. They were also aware that it was imperative to practice industriously and intelligently, to gain the necessary long-range experience the Irish already had, and share among them what was learned in the process.

By the time the Cunard steamer docked in a New York harbor on September 16, 1874, to deliver the Irish contingent, the Amateur Rifle Club was prepared to meet them. With the industry, community support and encouragement, together with proper rifles and intelligent practice, the Club had blossomed into a crew of top-flight riflemen.

The Irishmen did not want for an opportunity to acclimate and familiarize with the American’s Creedmoor Range. Two days after they landed, on September 18, 1874, several of the Irish team toured the range and were encouraged to shoot the Remington Diamond Badge Match the next day. There were other opportunities for the visiting team to practice, side by side with the American team, before September 24th when the eight Americans and six of the Irish gathered for a preliminary “easy gallop”, in the vernacular of the Irishman. This was a rehearsal match of the main event championship match that they had traveled to the United States to participate in. The match that counted would be shot two days later.

The outcome of the main event match of September 26, 1874, did much for American pride and confidence, and demonstrated to the Irish and the world that the U.S. could put together a real rifle team on short notice. The win or lose result, an oft-told tale that doesn’t get tiresome in its re-telling, came down to one shot that rested on the shoulder of a man who had just cut his firing hand on a broken bottle. John Bodine (thereafter, known also as “Old Reliable,”) centered the winning shot in spite of his bleeding hand. The most imaginative mind would be hard pressed to dream up a series of events as unlikely as the truth, and a finish more dramatic and impactful than it actually was.

According to Major Leech of the Irish team, the Bennett Cup Match was shot on Friday, October 2, 1874. Leech also recorded that the course of fire was 15 shots at each range of 800, 900, and 1,000 yards.

Straightaway, it became obvious to everyone that the contest would narrow to either America’s Fulton or Irishman Rigby, claiming the First Prize Bennett Cup. Each was equally regarded as the “man to beat”. Indeed, they were neck and neck for the top spot until the final shot. Unaccountably, Fulton missed the center and dropped five points he couldn’t afford to lose.

Fulton used an unorthodox method of muzzle loading his Remington breechloader. Most seated the bullet onto a charged and chambered case. Mr. Fulton poured the powder charge down the bore into the cartridge case via the muzzle. This worked well for him, until it was utterly vital that it did. The thought among spectators was that something went haywire during the loading process. Mr. Rigby won the prize with one of his own muzzleloading rifles. Fulton’s second place finish and a $100 prize may have consoled the youngest man on the American squad.

Mr. Rigby received his silver trophy bearing the inscription: “Presented to John Rigby by the National Rifle Association on behalf of James Gordon Bennett, Esq. as the competitor making the highest score in the Bennett Long Range Match, Creedmoor Range, New York, USA October 2, 1874.” Included was his shot-by-shot score at each distance of the match totaling his first place 159 total points.

Bennett’s New York Herald responded to the appeals of the Irish-American readership to publish coverage of the matches. The Herald went a step further in its accommodation and published facsimiles of winning targets. These were then forwarded to Forest and Stream magazine for an even wider distribution.

After the Bennett Match, the victorious Mr. Rigby, together with teammates Milner, Johnson and Kelly, boarded a car furnished by the Erie Railroad for the grouse fields of Kansas and Nebraska for some wing shooting. This guided excursion was part of the American show of hospitality for its foreign guests, and arranged and conducted by the editor of Forest and Stream magazine.

Gordon Bennett continued to be known for his generosity. He donated a valuable cup for the winner of a common pigeon shooting handicap that was held at the Jerome Park (West Bronx) that December of 1874. The cup was the incentive that occasioned the remarkable surge of early entries that were received. Mr. Bennett continued to underwrite the match expenses for the NRA and continued to be the source of coveted prizes during the era.

The Bennett Match will always be overshadowed and secondary to the great American victory at Creedmoor on September 26, 1874. In its own right, though, it represented one man’s generosity to his fellowman, and a symbol of one of the most overlookable events in shooting history.