The Wyoming Schuetzen Union’s “Center Shot”

Wartime Cartridge Cases

column By: Jim Foral | March, 23

With this sudden press of wartime ordnance production came the occasional and marginally excusable lapse in Frankford Arsenal’s usually rigid standards. One such timesaving measure was a shortcut in cartridge case annealing. A day’s production numbers were the figures that really mattered, and would have been correspondingly reduced, if the brass case had been allowed to linger in the flame the prescribed second or two longer to achieve the standard anneal. The bottom line is that there were no immediate or short-term consequences to this minor corner cutting. Earl Naramore, in his 1937 Handloader’s Manual, offers both explanation and justification. “This ammunition was made with the belief that it would be used within a relatively short period of time.”

Supplying the American Expeditionary Force from across “The Pond” was a monumental headache fraught with many yet-to-be-seen logistical difficulties. A step in the right direction towards simplification of ordnance inventory involved limiting the variety of rifle ammunition types; having one .30-caliber ball cartridge that would surely function and perform well in each of the 10 weapons chambered in .30-1906. This tally included no less than eight different types of machine guns and two bolt-action infantryman’s rifles. Paring the variety to a single all-purpose choice simplified supply and eliminated confusion in the long run and made the management of munitions less of a challenge.

Frankford Arsenal production for 1917, was divided into three classes based on a good, better, best foundation. Ammunition inspected to fall into Class A-1 had to meet a more demanding inspection and was the finest possible of the lot. A-1 cartridges were set apart for aircraft machine guns only. The Marlin machine gun, mounted ahead of the cockpit between gunner and propeller, was synchronized with the plane’s propeller to fire between the blade and gun alignments. In a dog fight, there was no margin for error and this is why the aviators got the best ammunition possible.

The rifle and machine guns of the ground forces received the B-1 grade of ammunition. Though perfectly useable, the last B-2 grade was not approved for combat and stayed stateside to be used to train troops. This third-rated class of ammunition showed minor cosmetic defects that did not affect functioning. Whenever an ammunition shortage resulted, these Class B-2 cartridges were reexamined somewhat less critically and the best of the “good” class was ultimately pronounced serviceable and made its passage overseas.

Sources agree that the entire Frankford Arsenal 1917 cartridge production was given an anneal known as the “machine gun anneal” to adapt more closely to the vagaries of that weapon. The Marlin machine gun, in particular, seemed to like this softer, stretchable case for dependably positive extraction during its particularly vigorous extraction phase.

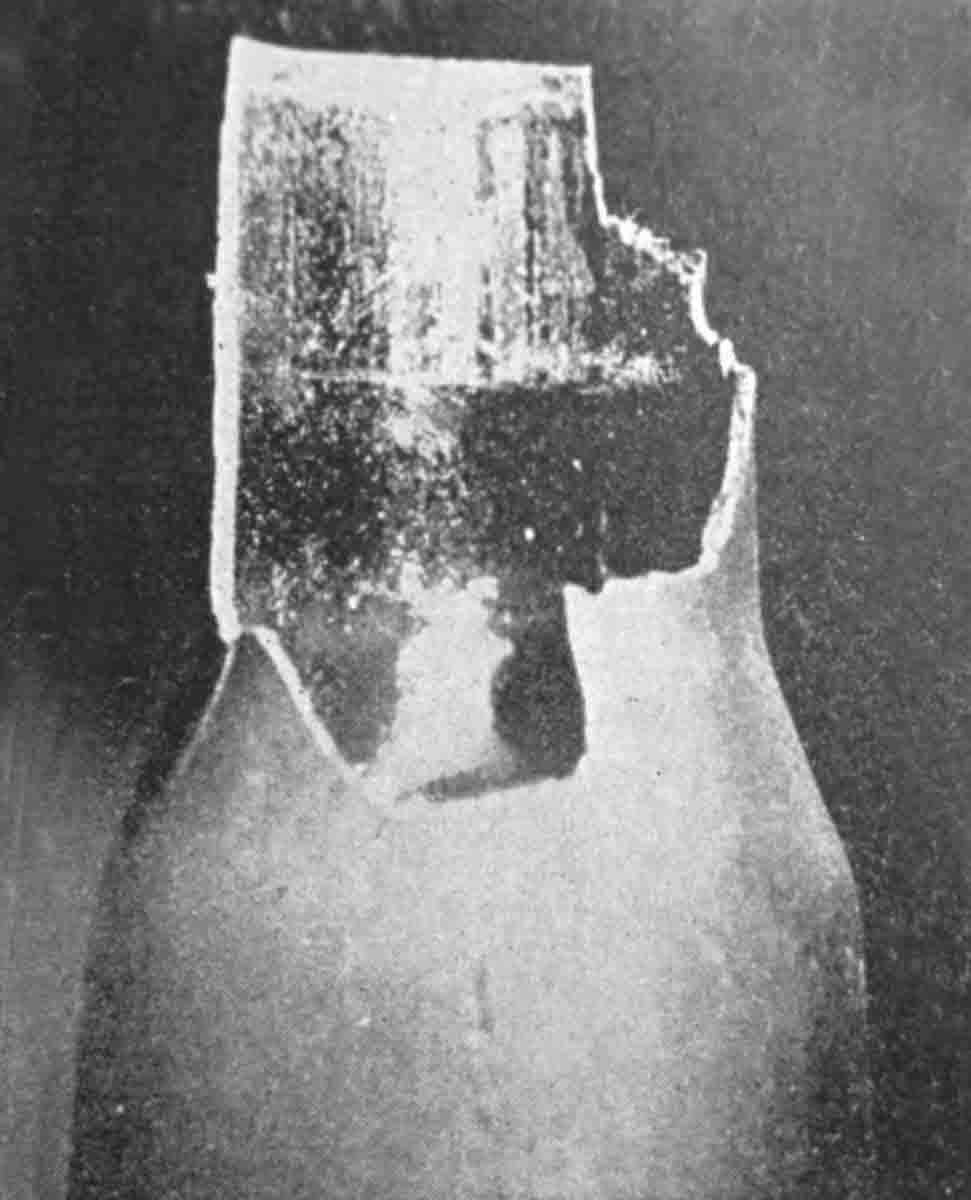

By the time they reached the end-user, the war surplus cartridges were on the edge of their shortened life expectancies. A fair percentage was smitten with a case of premature “season” cracking. “Shoot them if you must” was the word of wisdom E. C. Crossman wrote of using the split neck cartridges in his offhand practice, and other than the shots printing just outside of the main group, there had been no other issues. Most cases would survive their initial firing, but those were now frail and had developed their soft underbelly. The real weakness of the case was its propensity to fracture incipiently in one location or another on the case shoulder or body. Reloading that case and firing it would very likely cause it to let go catastrophically.

Readers of Arms and the Man were repeatedly warned to avoid these deathtraps and under no circumstances were they to reload the cases with any sort of charge. There is always a segment of the population that ignores warnings of any sort, and predictably, injuries were not unheard of. The more casual non-NRA member oftentimes was least likely to get the news. For the good of them all, Townsend Whelen teamed up with handloading authority J.R. Mattern for the extra weight his byline carried. They published Wartime Cartridge Cases – A Caution, which prominently appeared in the October 1923 Edition of Outdoor Life. Whelen pulled no punches in sounding the alarm, and left no doubt about the seriousness of reusing those Frankford Arsenal cases when he wrote: “During the past year we have had so many complaints from riflemen using such cases, and have heard of so many serious accidents resulting from their use, that the time has come to emphatically caution riflemen against their use for anything but reduced loads, and for those only when the case shows no sign of cracks in the neck.” The pair of experts agreed that using cases with cracked necks is never a good idea, but under the circumstances, a bad neck made the whole case doubly suspect. It wasn’t long before an authority with army ordnance advised that the fired cases were unsuitable, even to be reused as blank cartridges.

Whelen and the undersigned Mattern both emphatically warned that, for the reasons given, those wartime cases were “absolutely dangerous to use, and should not be reloaded under any circumstances.” The two men anticipated certain reader’s questions and headed them off. Wartime cases for the .30-1906 and .30 Krag had headstamps containing the initials of the manufacturer and the month and year of manufacture, and were identified that way. Good commercially-made cases carried the name of their maker and the caliber.

Those who preferred to reload Frankford Arsenal shells were advised to procure the arsenal brass headstamped “FA 22 R” or “FA23 R.” The “R” stood for the hard rifle anneal given and contrasted to the softer machine gun anneal. This was top quality current brass issued to competitors at the National Matches. We are to understand that brass scavenging and hoarding at Camp Perry during those years was very actively done.

During times of war, a government’s military needs to be seen as a model of superior strength, might, and numbers. While the truth may be less than this, and if there have been miscalculations or bungling on their part, it is important to remember that the enemy reads our newspapers, too. There would be plenty of time for a post-war analysis of the entire defense system and what was learned from making mistakes. Almost a year after the Armistice, Assistant Secretary of War, Benedict Crowell, gave a condensed account of the unexpected wartime obstacles that cropped up within the sphere of ordnance. He began by putting the pace and material imperatives into a relatable nutshell by comparing an annual (1916) peacetime cartridge production of 100 million cartridges to the wartime total of 3.5 billion.

In his post-war divulgement, Secretary Crowell defended the panel faced with a tough decision when he wrote: “It was found in a joint meeting of ordnance officers and ammunition manufacturers that certain increased tolerances could be permitted without affecting the serviceability of the ammunition.”

Pushed at this feverish pace, there were mistakes and failures that could afterwards be confessed to and learned from. The war had been a learning process and the cutting of corners and lowering standards and specifications when there was no time and no options was a forgivable part of the lesson.

Frankford Arsenal got a service-wide warning not to reload F.A. cases circulated post haste, while they devoted their attention to this matter. At the same time, Winchester’s ballistic labs were getting reports of the same phenomenon occurring with its smokeless powder cartridges. At once, they issued a circular that cautioned – “Reloading Smokeless Cartridges Impractical” and placed labels on appropriate cartridge boxes that read like a warning. Both Frankford and Winchester prioritized finding the root cause of the trouble.

Since it was the cartridge case that had failed, its examination was considered first. On the surface, there seemed nothing inherently suspect about this inert tube or brass formulated to government specifications of 70 percent copper and 30 percent zinc. Contractor-supplied lots of raw brass underwent a rigid inspection and analysis to ensure it met specifications. A series of 10 cases were made from each lot, which were then fired and reloaded until a sample failed. The average case endured 18.5 loadings before it showed the slightest failure. That lot of brass was then given a clean bill of health.

The search narrowed. The problem was unique to smokeless powder loads and the accusing finger was next pointed at the propellant. However, after chemically examining burnt powder residues, the considerable staff of ballistic experts agreed that there was nothing in the powder’s makeup to cause or contribute to the mysterious failure. Chemically, it just didn’t make sense. Still, they tested to exhaustion to confirm their suspicions.

Next in line under the microscope was the primer, sheepishly hiding in its snug little pocket and trying to look innocent. The chemist’s logical focus was on the priming compound, comprised most actively of fulminate of mercury. The fulminate is an unstable explosive compound that had a lot of ordnance applications. Frankford Arsenal went through great quantities of fulminate of mercury. Frankford Arsenal’s ballistic engineers learned and understood that mercury amalgamates with the brass of the case the instant the primer is fired, and then the zinc in the case is attacked by the quicksilver, making it brittle. Black powder cartridges fired with the same primer were immune, owing to the spray of fouling deposited on case walls that acted as a barrier, preventing the fulminate from attaching.

The Annual Report to the Chief of Ordnance nutshelled the chemist’s findings into a tight little space. The cause of the brittle ruin of Frankford Arsenal cases, and those of other manufacturers, had been isolated and at last traced “to the action of the mercury in the priming composition reacting to the metal in the case, particularly on the zinc.”

In selecting a priming compound for the new smokeless powder, focus seems to have been on its beneficial attributes, while any drawbacks may have gone unconsidered or unknown. Live and learn.

In the report to the chief of ordnance for the year ending June 1900, is found notice that a new F.A. 30-caliber primer, faultless and mercury-free, would be the standard U.S. rifle primer. Known as the H-48 primer, for many years, it was the favored primer by all of America’s military marksmen.