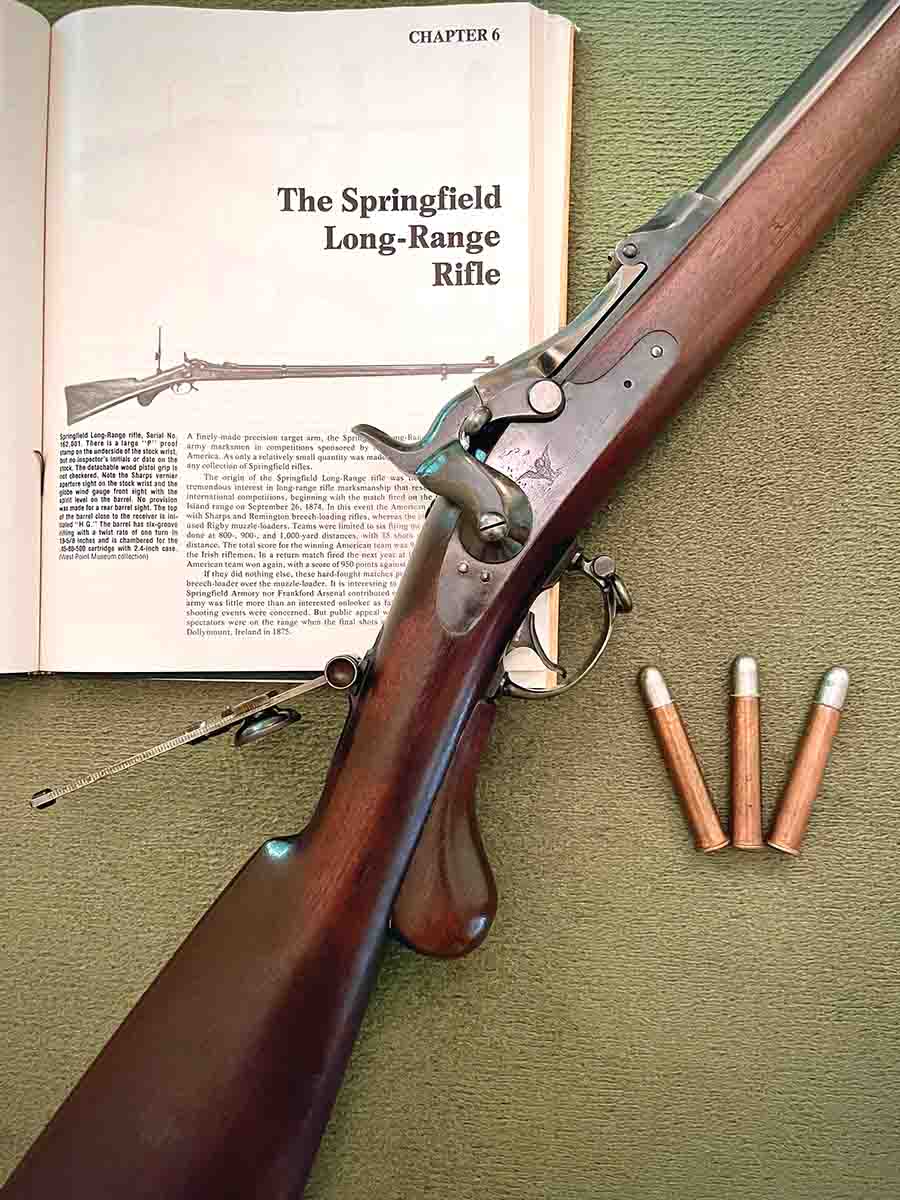

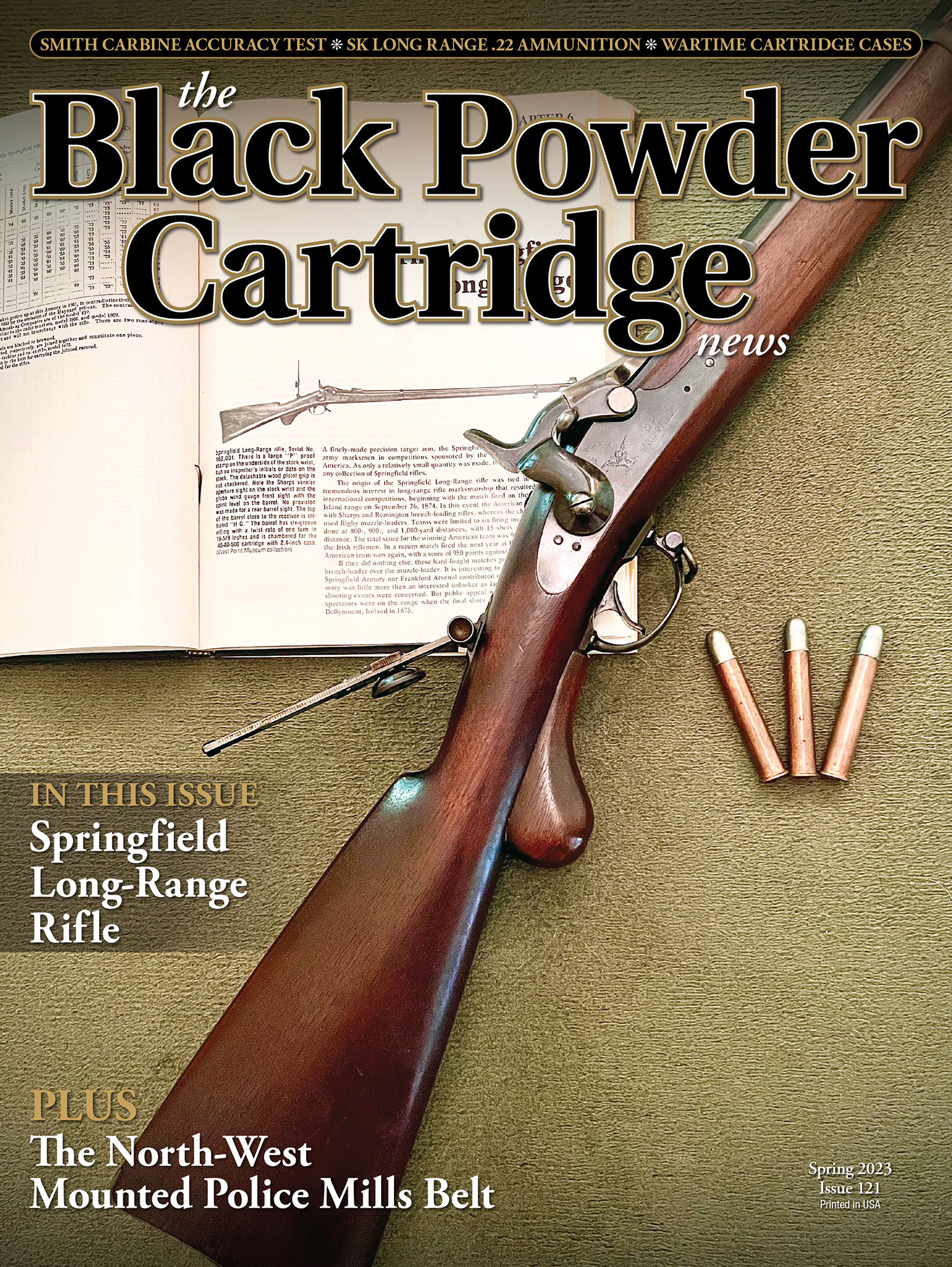

The Springfield .45-80-2.4 Long-Range rifle.

Most of us who shoot black-powder cartridge rifles are familiar with the Creedmoor long-range rifle matches of the 1870s. This was initially a civilian activity with rifles provided by the Sharps and Remington companies. The army eventually wanted to get into the game and began experimentation to determine the necessary modifications to the standard service rifle to make it competitive out to 1,000 yards. The rifle in the accompanying photos is the result of several years of the army’s effort to produce a long-range target rifle.

Background

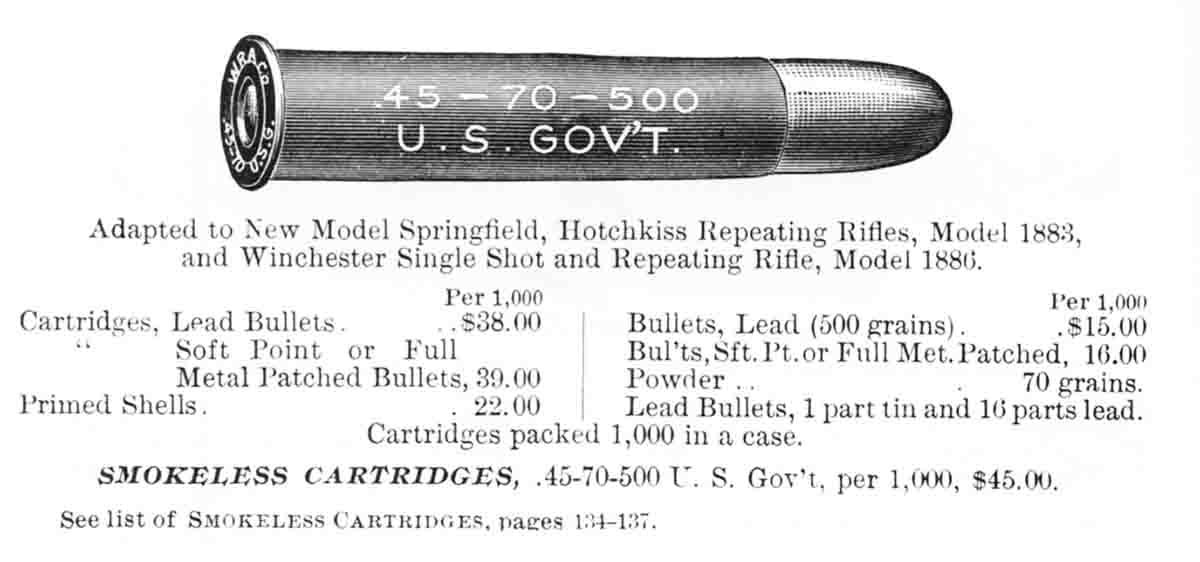

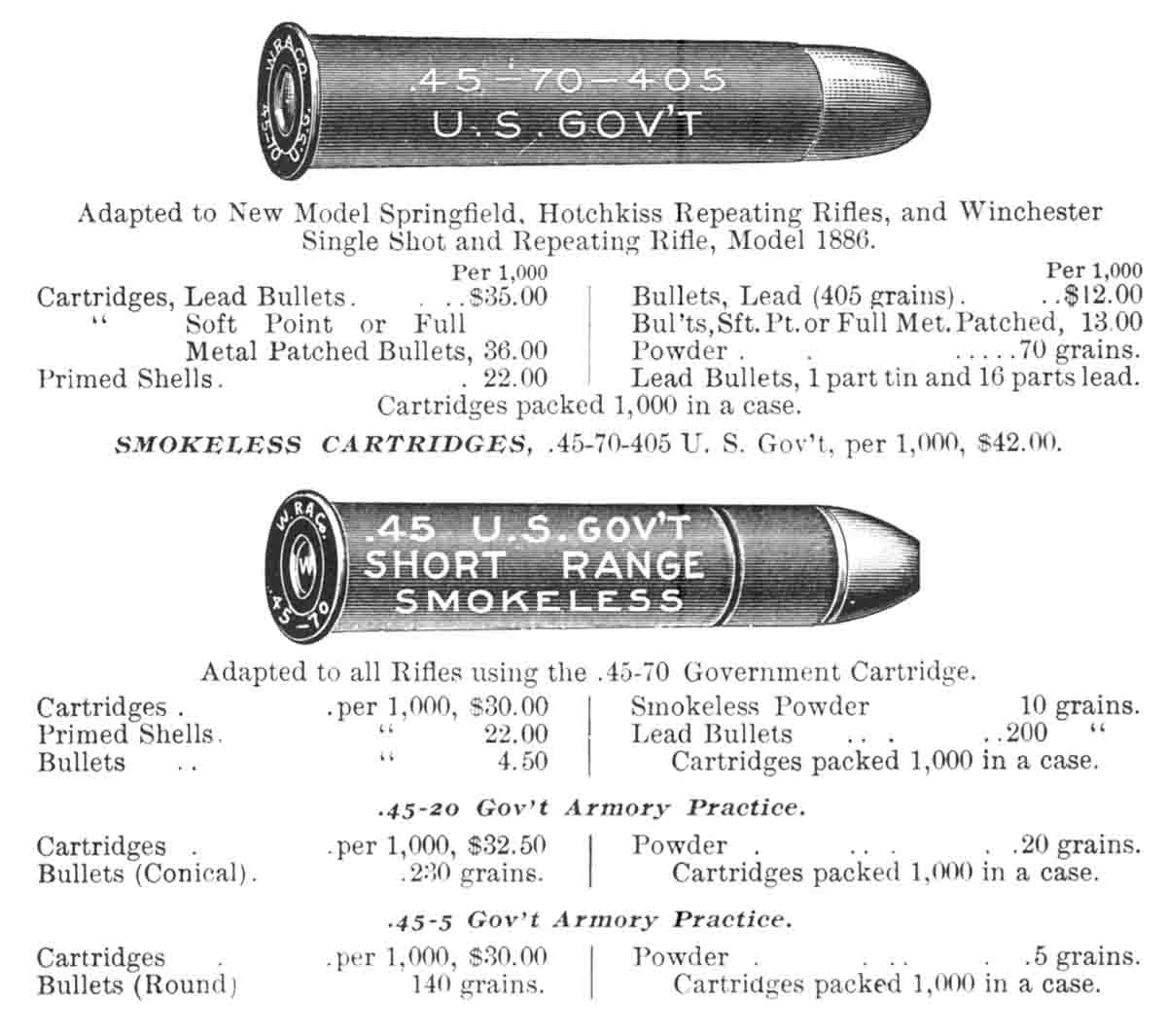

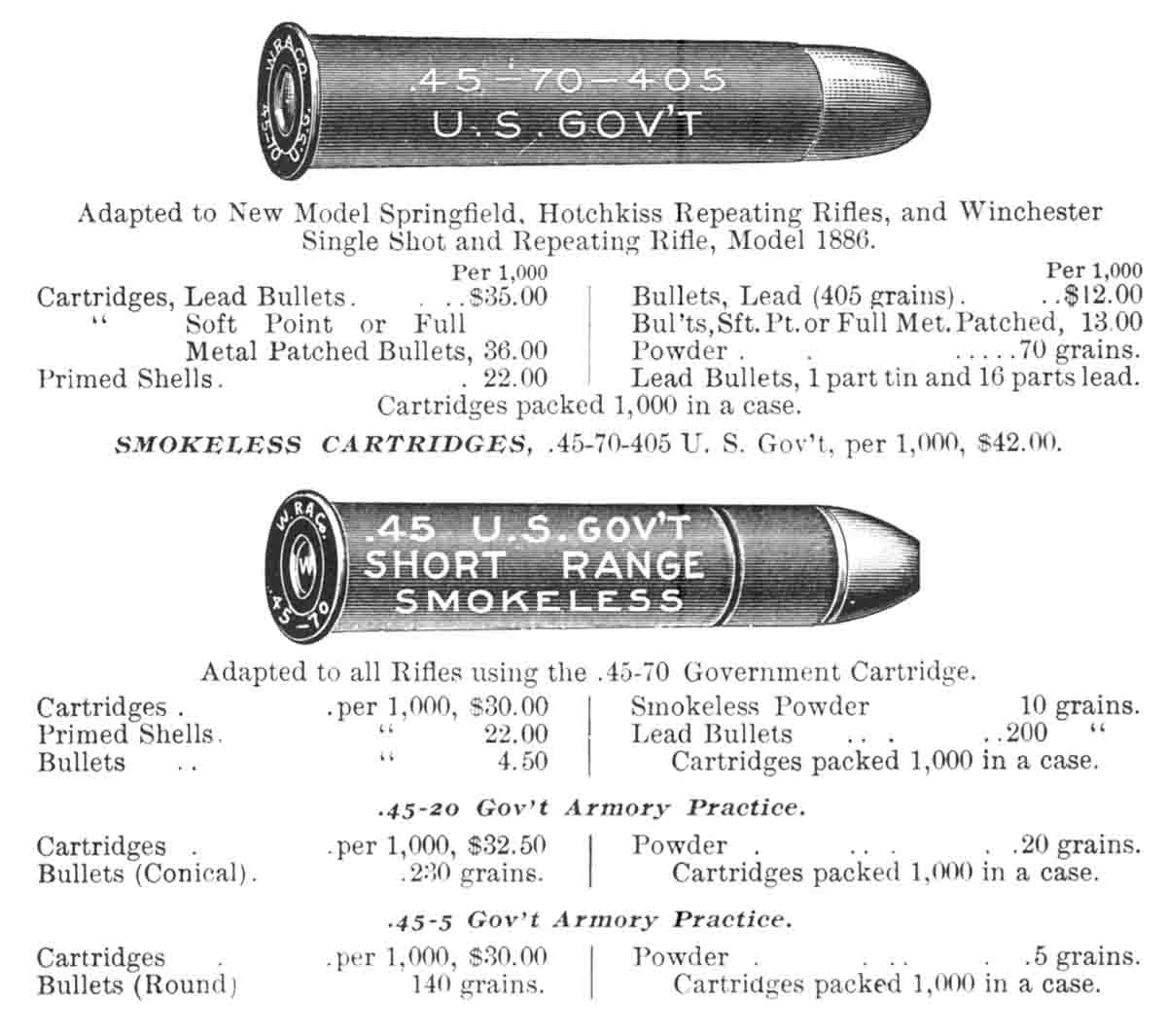

The standard service rifle at the time utilized a 405-grain, hollowbase bullet loaded over 70 grains of powder in a 2.1-inch cartridge case. This produced a muzzle velocity of approximately 1,350 feet per second (fps). The rear sight was barrel-mounted, with a ladder elevation graduated to 1,100 yards, but had no provision for windage correction. It soon became apparent to the testers that in order to shoot well at 800, 900, and 1,000 yards, they would need three things: a heavier bullet, a bigger powder charge and better sights.

In 1879, approximately 20 rifles were produced at the Springfield Armory for experimentation, as well as use in competition by an army rifle team. These rifles had six-groove rifling (standard was three-groove) and were chambered for the 2.1-inch case with a modified throat to accommodate a 500-grain paper-patch bullet. This was loaded on top of 80 grains of black powder plus a lubricating wad. While this performed well, it barely allowed the base of the bullet to fit inside the case mouth, making the load very delicate and, the army believed, impractical. A screw was added to the base of the rear barrel sight to allow for windage adjustment.

In the spring of 1880, the commanding officer at Frankford Arsenal proposed a reloadable cartridge utilizing a 500-grain, grease-groove bullet over 80 grains of powder loaded in a 2.4-inch case. Subsequent long-range rifles would be made with a lengthened chamber to accommodate the longer case. It was while testing loads for the target rifle that the army discovered they could increase the effective range of their service rifle by several hundred yards simply by increasing the bullet weight from 405 to 500 grains. This was adopted as the standard rifle bullet in 1881. This original M1881 Springfield bullet is the forerunner of the 520-grain Lyman 457125 bullet still popular today.

A Long-Range (Hotchkiss) buttplate (top) is shown with a standard trapdoor buttplate (bottom).

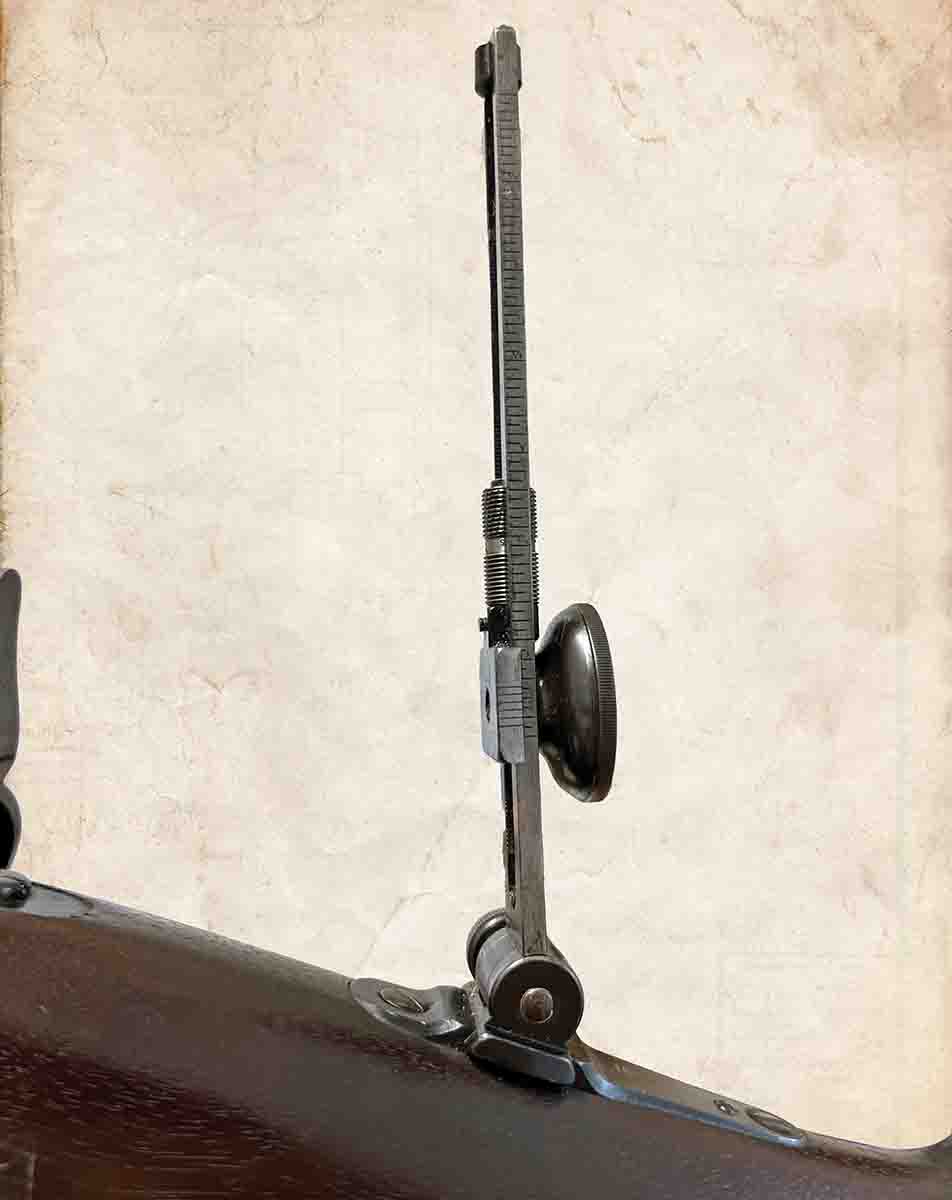

By April 1881, the army finally had all their ducks in a row and the Springfield Armory got busy producing 151 of the new long-range rifles. Chambered for the .45-80-500 cartridge with the 2.4-inch case, these rifles had six-groove rifling and the Hotchkiss-style shotgun buttplate. Some were equipped with a detachable wood pistol grip. According to Flayderman, 24 of the rifles were made with the Sharps Borchardt vernier tang sight, the remainder having the modified Bull barrel sight with windage adjustment.

The Rifle

Chris Fantini’s Springfield .45-80-2.4 Long-Range rifle.

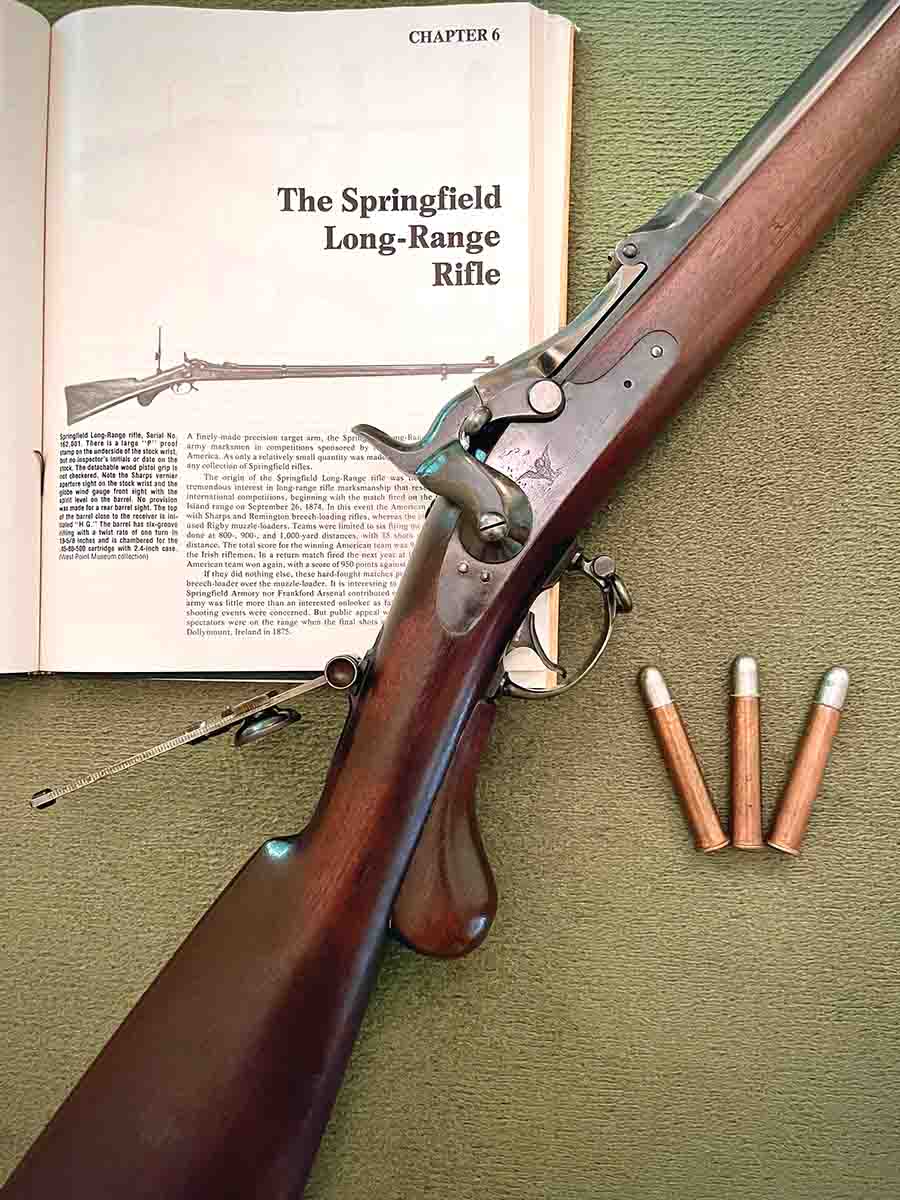

The rifle in the photograph is one of the 24 produced with the Borchardt

tang sight and no provision for a rear barrel sight. My father acquired

it while collecting antique rifles in the New York City area shortly

after the World War II. Serial number 162,012, six-groove rifling, with a

twist rate of one turn in 195⁄8 inches, Hotchkiss buttplate, detachable

pistol grip, corrugated trigger, windage adjustable globe front sight

and it is chambered for the 2.4-inch cartridge.

The .45-80-2.4 cartridge.

To meet Creedmoor criteria, rifles could not weigh more than 10 pounds or have less than a 3-pound trigger pull. This specimen tips the scale at 9.1 pounds. I do not have a way to measure trigger pull, but comparing it by feel to two other Trapdoors in my collection, I suspect it is in the 5- to 6-pound range. Suffice to say, that recoil and trigger pull are significant factors. This is not like shooting a silhouette rifle.

Shooting

I remember standing in my father’s gunroom when I was about eight or nine years old as he patiently showed me some of the antique collection that I found so fascinating. When he came to this rifle, he said “Now, we never want to shoot this one, it’s in mint condition.” Until I began shooting the rifle a year ago, it may never have been fired since leaving the factory. I decided it would be a shame to have it eventually wind up in a museum never having been put through its paces.

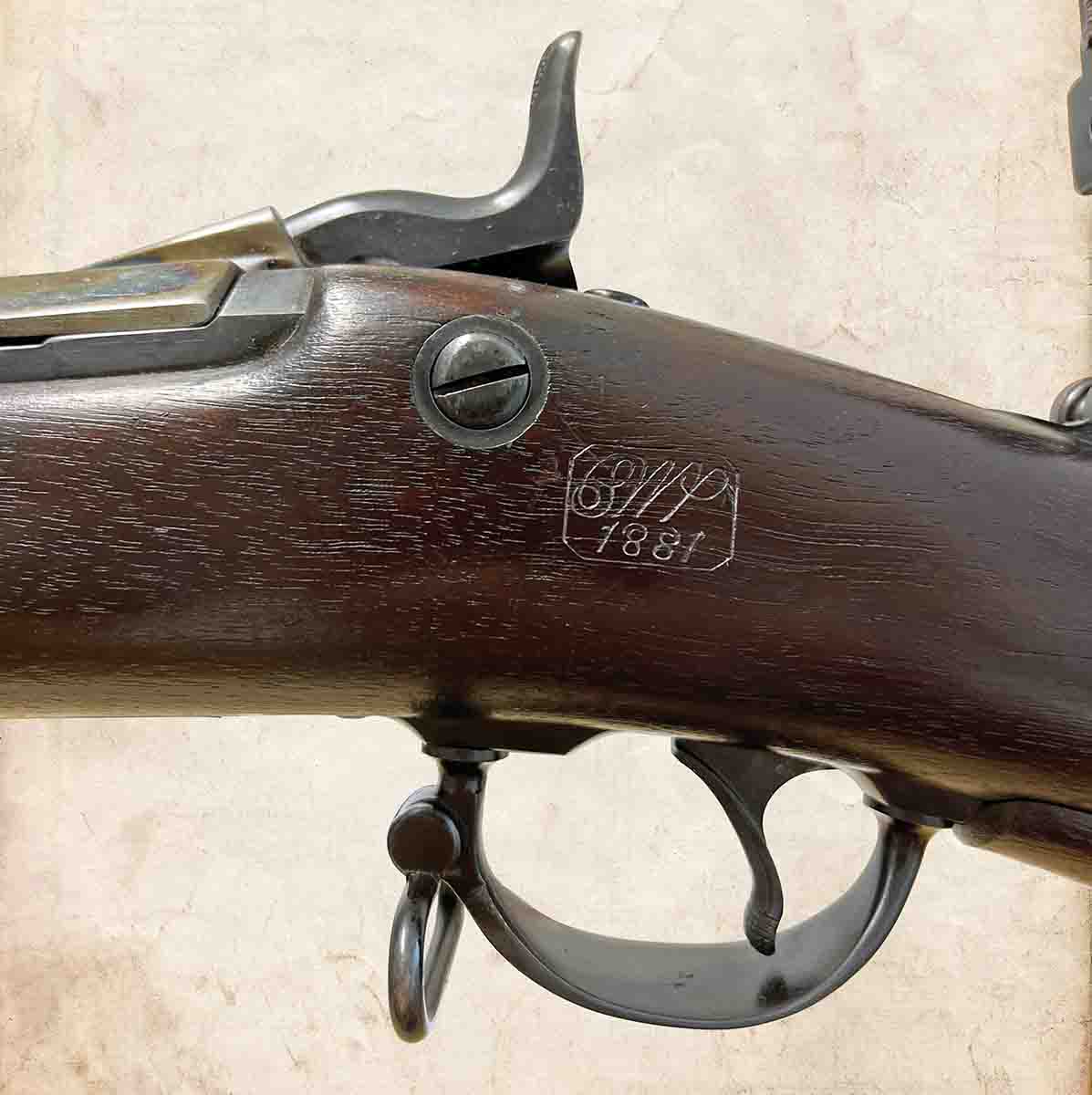

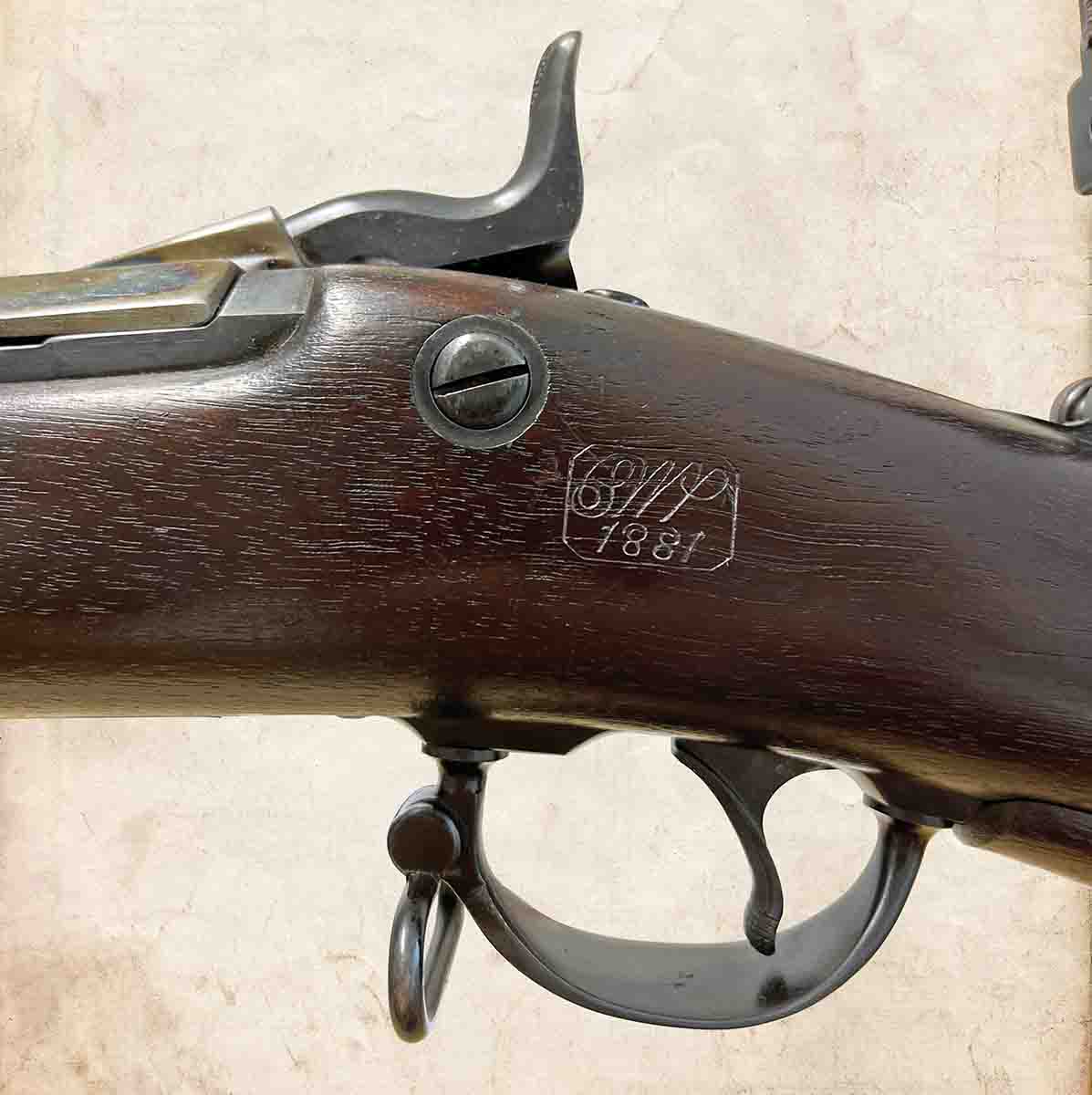

Inspector’s cartouche on the Springfield Long-Range rifle.

My first attempt was with a version of the original three-groove M1881 Springfield bullet that I had acquired years ago from Montana Precision Swaging. This was loaded over 68 grains of Swiss 1½ Fg with a .060 card wad. The first target at 100 yards was mediocre, but things improved when I switched to the 520-grain Lyman 457125 bullet. As groups approached 2 minutes of angle, things looked promising and targets were moved out to 170 yards, the distance that is easily negotiable at my local club.

I knew what I wanted: a perfect minute and-a-half of angle, 10-shot group with no fliers. I just didn’t know what was reasonable to expect given a 140-year-old rifle and my aging eyes. I began my trip down the rabbit hole of load development.

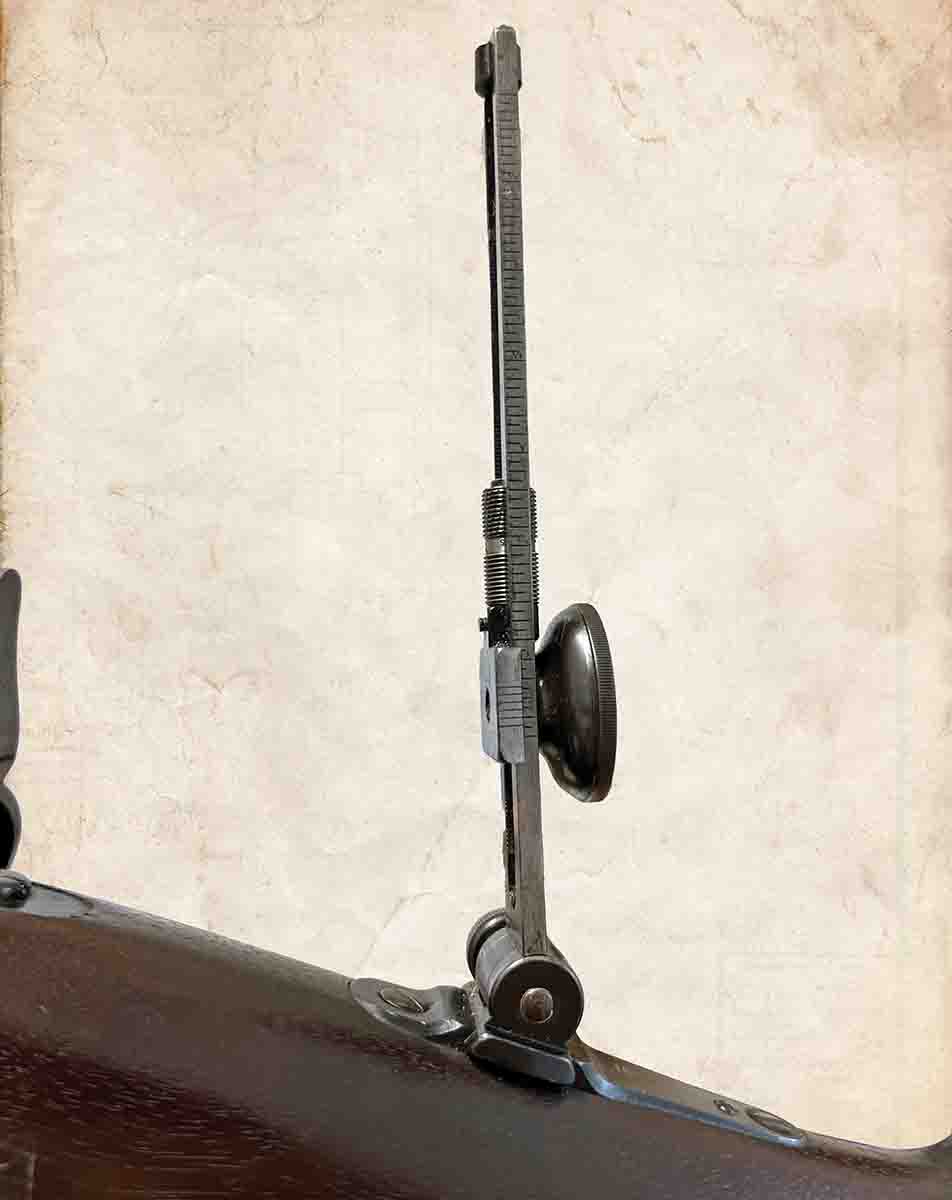

Sharps Borchardt tang sight on the Springfield Long-Range rifle.

Testing was frustrating, as I would invariably throw one or two rounds outside of a promising group when testing 10 shots. This was just as likely to be me as the load. I decided to try a 500-grain paper-patch bullet that shot very well in my Shiloh Sharps .45-90. No luck.

I tried the Lyman 535-grain Postell, which performs well in my Remington Rolling Block. Again, no luck. I was able to acquire some original cartridges loaded at the Frankford Arsenal for the long-range rifle. These provided me with an accurate measurement of the overall length and demonstrated a moderate crimp. I tried reproducing this load using the Lyman bullet over 80 grains of Swiss 1½ and giving it a moderate crimp to the loaded round. This load required a lot of compression, but it didn’t group very well. Throughout all this, I had more than a couple of case separations, never a split case, always a clean separation approximately ¾-inch up from the base. Nevertheless, I soldiered on.

Bullets used in the Springfield Long-Range rifle. Left to right, Montana Precision Swaging 500-grain, Lyman 535-grain Postell, 500-grain paper patch, and Lyman 457125.

As can be seen in the photos, a couple of targets were shot at 170 yards. I thought this load was worth testing at 300 yards and the weather finally cooperated to allow this. The load was as follows: Winchester brass, fireformed and neck-sized, expanded enough to start the base driving band in the case and give about .002 inch of neck tension; 74 grains of Swiss 1½ Fg, drop-tubed and covered with a .060-inch wad; just enough compression to ensure no airspace, about .030 inch; Lyman 520-grain bullet loaded with the first grease groove exposed and SPG Lube, of course. Winchester Large Rifle primers were used and the overall cartridge length was 3.185 inches, which is about the maximum that will chamber.

Case separations in the .45-80-2.4 Springfield.

Case separations had whittled down my inventory to 15 rounds, so I loaded these and went out to the 300-yard range. The wind was gusty coming over my right shoulder, not ideal conditions, but not terrible. A best guess at sight elevation brought me on target after four shots. This left me 11 rounds to shoot for a group on a clean target.

Two fliers went out at one and seven o’clock, the remaining nine grouped into 53⁄8 inches horizontal and 57⁄8 inches vertical (see photo). Three case separations occurred in these last 11 shots, which may have hurt the group. Overall, not the best, but not terrible either.

I wish I could report that I had gotten this gun to shoot the wings off a gnat at 300 paces. What I can say unequivocally is that messing around with this beautiful old rifle for the last year has been an incredible amount of fun. It was often a topic of interest and admiration at the range. So many shooters have seen or owned Trapdoor Springfields “… but I never saw one like that.”

Epilogue

So, what happened to these fine specimens? Well, within months of producing this last batch of rifles, the army decided it was too expensive to send rifle teams to the international competitions and suspended the program. They substituted an intra-service marksmanship program, which would only allow use of the standard service rifle and ammunition. Some of the long-range rifles were distributed to different army units for practice and experimental purposes, but could not be used in competition. Once smokeless powder was adopted in the 1890s, the remaining rifles were sold as surplus. According to Bud Waite’s excellent book Trapdoor Springfield, in 1907, the Francis Bannerman catalog listed 60 long-range rifles selling at $6.80 apiece. A box of 20 cartridges was thrown in for free.

“This is the way the world ends: not with a bang but a whimper.”

– T.S. Eliot