The Wyoming Schuetzen Union's "Center Shot"

An Interesting Exhibit

column By: Jim Foral | August, 19

Theodore Roosevelt’s celebrated 1909 African hunt made him the toast of America’s press and the talk of its citizens, but to many entrepreneurs it represented another fresh profit angle not to be overlooked. Some of these were known to push the limits of good taste and fair play.

On the off chance that it would be used and mentioned, Webster Marble of Marble Safety Axe had delivered to the White House his entire, unrequested, and complimentary line of outing equipment. He then made an advertising point of it. Marble had sent the same kit to the office of Dr. Frederick Cook, a claimant to the discovery of the North Pole in 1908. “Marble goods to the North Pole”, his ad read – and maybe they were.

With whatever hopes he may have had, a minor manufacturer of inexpensive cutlery sent to the Oval Office an unsolicited folding knife and soon billed it as “the knife Roosevelt carried in Africa”. The magazines carried his illustrated ad.

America’s gun makers proved themselves not above pulling the same sort of stunt. They, too, tried to jump aboard the gravy train without buying a ticket, never minding that the president had ordered far in advance what repeating rifles he should need from Winchester. When the time came to ready the rifles, T.R. requested that the “Big Red W” make available the services of their agent, Captain Albert L. Laudensack, to assist him in adjusting the sights.

By 1909, Captain Laudensack had compiled an impressive resume. At Winchester, he was an ordnance engineer and a capable research and design specialist credited with several design improvements and modifications, and a small number of patents assigned to Winchester. He was the guiding force behind the Winchester Junior Rifle Corp. Laudensack was a member of the company Schuetzen squad, range master at the company range, and a high-profile competitor excelling in many disciplines. Albert Laudensack was a decided asset to the firm and the model “company man”. Just as importantly, he possessed an innate flair for public relations.

According to the unpublished post-retirement memoir of Winchester executive Henry Brewer, Laudensack met with Col. Roosevelt at the White House and the two headed to the basement where the staff had prepared a short range. One by one, they proceeded to sight-in each rifle on the makeshift range. After breaking for lunch with the first family, they returned to the basement and finished their work. All the while, T.R. and Laudensack chatted — gun crank to gun crank — about their common absorption with guns and ammunition. Laudensack reported to the W.R.A. office that he’d had the time of his life.

Roosevelt had a very extensive outfit assembled for his African departure. It had come from various sources, and to each the President had issued a special stipulation that his purchases were not to be used for advertising purposes. T.G. Bennet, Winchester’s president, had gotten the message and passed it along to William R. Clark, the gun maker’s Advertising Manager, making himself doubly clear concerning the presidential directive. Clark was particularly watchful that the letter of his instruction wasn’t violated, but did become craftily creative in circumventing its spirit.

Long before Col. Roosevelt departed for the “Dark Continent” in April of 1909, Winchester Repeating Arms had already a plan in the works to capitalize on the tremendous public interest the African trip had engendered. In preparation for this rare and fleeting opportunity, the company had readied a traveling exhibit of duplicated Roosevelt-ordered Winchesters together with a showcasing of enough “highly finished” specimens of the firm’s other models to blur the exhibit’s actual focus. It might have been hoped that straddling the indistinct gray line between advertising and not advertising, the gun maker could arguably be seen as compliant with the president’s ban on commercial exploitation.

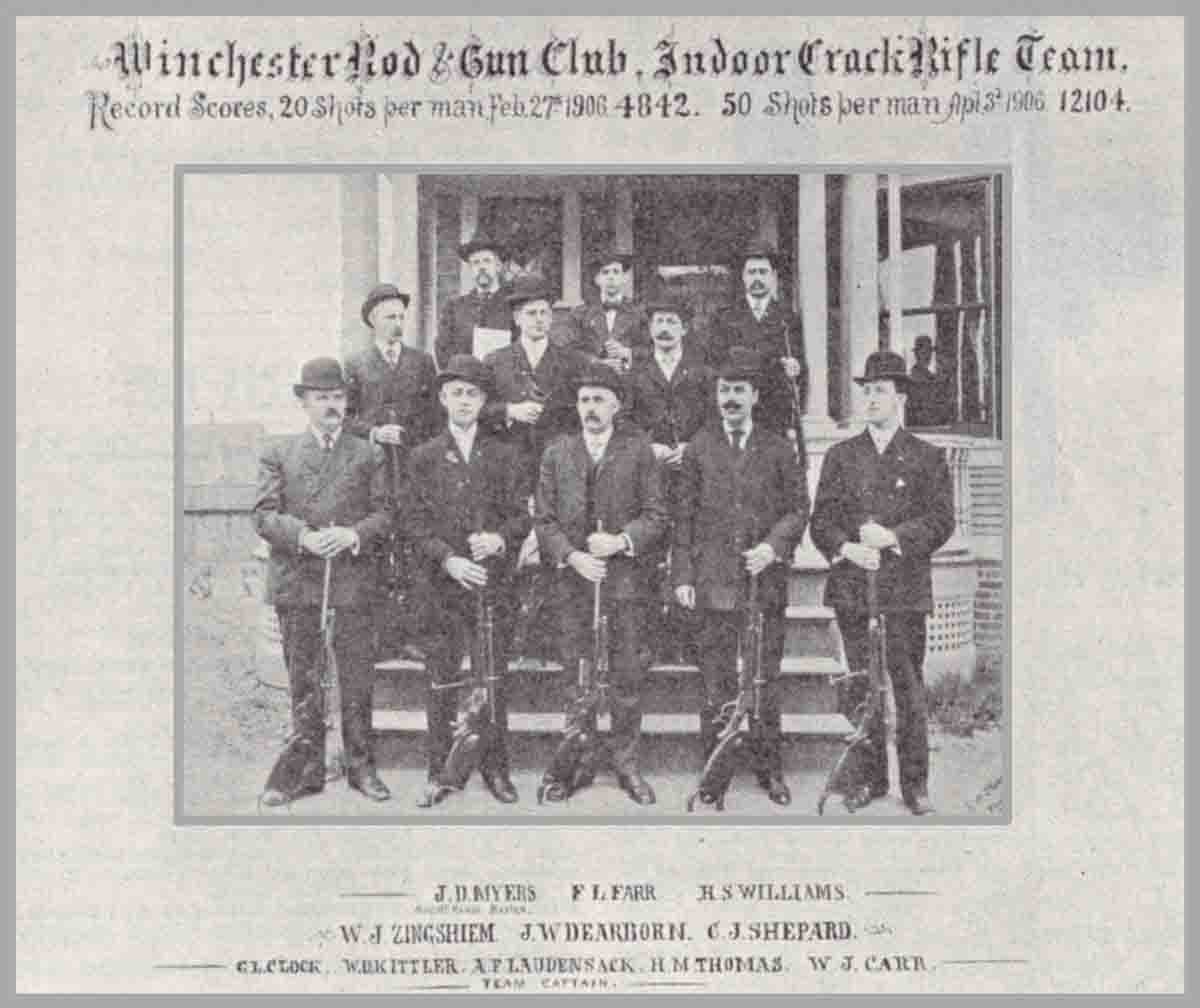

Charged with conducting this cross-country pilgrimage was Capt. Laudensack. He was given three able assistants, all Winchester reps accustomed to being on the road. The display was said to have included twenty-three guns, though only nineteen were shown in a picture taken at the Milwaukee stop. Above the display table hung a poster of Capt. Laudensack.

The personal battery of Mr. Roosevelt that Winchester furnished consisted of three Model 1895 lever-action rifles chambered .405 WCF, and another ’95 taking the “.30 rimless” shell (.30-1906 Springfield). Each of the ‘95s had 24-inch barrels, fancy cheek-piece stocks with Silvers recoil pads and were extensively engraved. A Model 1897 12-gauge represented T.R.’s preference in repeating shotguns. Like his other choices, it too was highly decorated. Two exquisite model 1903 .22 Automatic rifles, identical to the ones ordered by the president were shown to confirm T.R.’s good taste in rimfires.

The other guns at the table were lavishly appointed examples of Winchester’s “bread and bullet” models. There was a deluxe High Wall Single Shot with the new take-down system, and another in Musket configuration. All of the basic lever-action models were represented, embellished to show what the gun maker was capable of. Two of the new Model 1907 self-loading rifles were also on display.

Surviving newspaper coverage of the course of the traveling exhibit is fragmented and incomplete, leaving big gaps in the show’s schedule and route. Enough remains, however, to provide the general idea. After departing New Haven, the first traceable stop was at the Rochester station for the April 26 and 27 engagement.

The Detroit Free Press printed on May 10 the news that the exhibition would be open to the public through the 12th at the Hotel Ponchertrain. On June 28, a notice in the Evening Herald alerted Duluth’s citizens to their two-day viewing of Winchester’s display. Three weeks later the Daily Missoulan covered the arrival of the exhibit’s train rolling into their station for a scheduled July 16-17 stay. On August 2, the exhibit’s arrival made the front page of the Sacramento Union, and with it Laudensack’s statement regarding the mistaken “general impression” regarding the former president’s primary mission in Africa. There was growing, by this time, a vocal segment that believed, and would have others believe, that the African trip was a “slaughtering expedition” where the president pulled his trigger on “anything that moved”.

Capt. Laudensack ably defended what was officially known as the Roosevelt – Smithsonian African Expedition as a primarily scientific one, sent for the purpose of collecting as many of the 30 or so species needed for the Smithsonian’s new Natural History museum. Capt. Laudensack was especially forceful in setting the record straight.

Immediately afterwards, the San Francisco Chronicle announced that the exhibit would set up at the Saint Francis Hotel for a four-day stint, August 4-8, 1909. Later that month the Omaha Daily Bee welcomed the exhibit to its Henshaw Hotel for the 16 and 17 dates. After the newspaper trail went cold, there was still a lot of time and ground to cover.

Since the tour was known to have been in the Milwaukee vicinity during the mid-May to mid-June window, it seems reasonable to deduce that this venue was visited during this time frame.

Bob Kane, the Arms and Ammunition Editor of the Milwaukee-based sporting magazine Outers Book, attended and wrote up the only surviving summary of the event and recorded it for posterity. His magazine claimed to have taken the only photograph of the assembly of guns, at least to that point.

Kane’s missive, unimaginatively titled “An Interesting Exhibit”, appeared in Outers Book, subtitled “A Magazine of Outdoor Interest” in August of 1909. Very likely Kane was unaware of the presidential edict. Kane’s prose, nevertheless captured what was plain to see, that the “…exhibit served as a splendid piece of advertising for the Winchester company.”

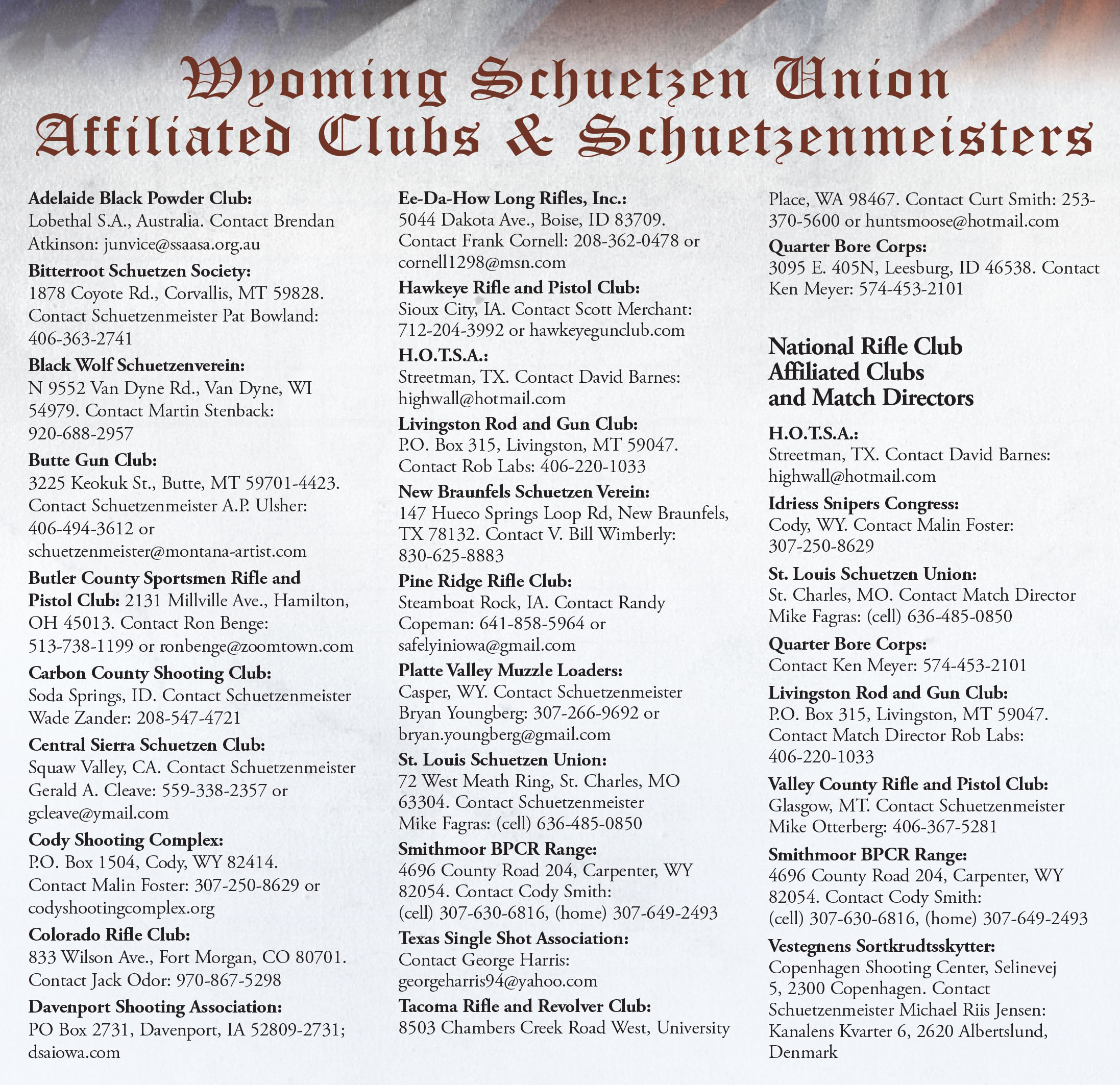

Wyoming Schuetzen Union Affiliated Clubs & Schuetzenmeisters