James H. Cook

Union Pacific Market Hunter

feature By: Miles Gilbert | August, 19

James H. Cook was born in southern Michigan on August 26, 1857, but his mother died when he was two. His father was a seafaring man and placed him with a family named Titus, who were one of the oldest and most respected families in that part of the state. They exhibited industry, frugality, integrity and “every Christian virtue.” The men took pride in their skill as marksmen and they taught the young Cook to become a master woodsman.

At age 16 he migrated to southern Texas and began the rough and tumble life of a cowboy trailing longhorns to Kansas, Colorado and Wyoming. In 1878, he met an old acquaintance, “Wild Horse Charlie” Alexander, in Cheyenne. Charlie had turned from catching wild horses to hunting and trapping. He had a Remington sporting rifle, a team with light wagon, a tent and camping outfit. Taking up Cook’s narrative there, we learn that:

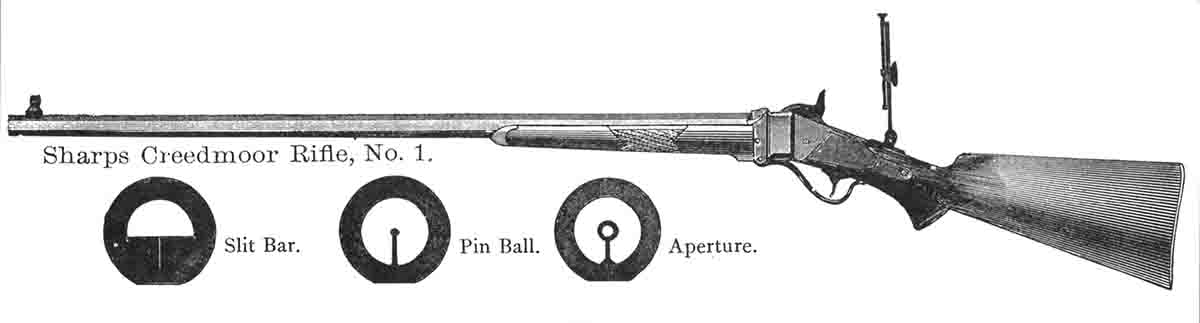

We became partners that day, and started out after some antelope for the Cheyenne market. We went down into Little Crow Creek, about thirty-five miles southeast of Cheyenne. There were plenty of antelope in that section. The first day we hunted, I did so well with my little (Winchester 1873) carbine that Charlie said, “If you can keep up this gait, all I will have to do is take the meat and hides in to Cheyenne and sell them.” I think I kept up my gait, for Charlie was busily occupied hauling game to market most of the time. We soon had money enough so that I was able to buy a very fine Sharps .40-90 target rifle, for which I paid $125. We loaded all of our cartridge shells and molded and patched our bullets. The prices we received for the antelope and deer meat ranged from five to eight cents a pound. The hides, when dry brought us from sixteen to twenty-five cents a pound.

(The market for bison hides is well documented. However, because antelope hides are so much less hardy, the market for them is less well known. In 1873 one broker in Iowa sent 40 tons of antelope skins to East Coast processors, and 53,000 of their hides were shipped down the Yellowstone River as late as 1881).

After hunting with Charlie a few weeks, I went into Cheyenne one day with him on a load of meat and hides. As I was going into the gun store of P. Bergersen I met…Mister Yale, the steward of the Union Pacific Railroad Hotel…Yale surprised me by stating that the Railroad Hotel and the eating houses of the Union Pacific Railroad in Wyoming used large quantities of game, and that he should be glad to aid me in disposing of all the game I could kill. I was delighted to hear this, for to me it meant a great deal. No more meat would have to be peddled out to butcher shops and private houses. I did my best to express my thanks to him for his kind offer, and introduced him to Charlie Alexander, my partner. The dealings we had with Mr. Yale in the months that followed were most satisfactory to everyone concerned.

Moreover, Colonel Jones of the Railroad Hotel, Cheyenne, became so interested in Charlie and me that he not only purchased game of us for the use of the hotel of which he had direct charge, but also shipped it to other eating houses up and down the line of the Union Pacific Railroad. The Colonel was a most genial host, and he had many friends and acquaintances among the travelers who were fed at his far-famed eating station. Among the gentlemen whom he met at Cheyenne were many who desired him to secure choice game for them for club dinners or other occasions. All such requests the Colonel turned over to me to fill, he himself attending to having the game shipped to various cities, from New York to San Francisco.

Charlie and I now had something to do. We took great pains to have the game we furnished dressed out and kept in the most cleanly manner possible until delivered-something that many hunters were often careless about. We also took great care in stretching, drying, and baling our hides for the market. The hide buyers of the great hide and fur house of Oberne, Hosick & Company of Chicago, which at one time had branch houses all over the West, complimented us on the condition of the hides and furs we sold them. In consequence, our bales of deer and antelope hides were not opened and inspected before paid for, for fear that damaged hides or a few pounds of dirt, gravel, or bones would be found inside. When we hunted too far away from Cheyenne to haul the meat to that city, we kept close enough to the UPR so that we could ship game regularly to our market. We killed many antelope, black- and white-tailed deer, elk, and mountain sheep during the time of our hunting in Wyoming and Colorado.

When we found that we could not supply the amount of game required, Charlie and I took in another partner by the name of Billy Martin. He was a good hunter. Both Charlie and Billy were very temperate men in every way. Neither had the drink or tobacco habit- something most unusual among hunters and trappers of that day.

When we hunted too far from the UPRR to handle our meat fresh, we built smokehouses and dried it. Our smokehouses were rather primitive in the manner of construction and material used, but the results obtained would compare very favorably with, or perhaps excel, those obtained by the great packing houses of recent years. Getting the empty whiskey barrels and salt to our camp (two most important necessities in pickling the meat preparatory to smoking it) was often a hard task, there being few wagon roads which we could use in getting to the railroad. When killing game in the mountains of Wyoming, such as elk, buffalo, deer, or mountain sheep, we took all game killed into camp on pack mules or horses.

As it was necessary to cut the heavy animals into quarters in order to lift and lash them onto our pack animals, we invariably before quartering them, cut out and kept intact long strips of loin meat, which were the choicest and most valuable part of all the meat we dried. In camp, we took all the meat from the bones of the animals, cutting it as little as possible, opening the partings between the muscles and leaving each group of muscles as near their proper form as possible.

(This is how European butchers continue to process large domestic animals.)

The meat was then placed in the barrels and brine poured over it until covered. It remained in this brine for nine or ten days; then it was taken out and hung up, each piece by itself, in the smoke house. We dug a long trench down a slope from our smoke houses, connecting these with the fireplace at the lower end of the trench. This trench would be covered with rocks and dirt, making a flue to conduct the smoke. Sometimes the trenches were as much as thirty feet in length, so that the smoke, when it reached the meat, would not be hot enough to injure it. As we could not remain in camp to attend the fire, we put a large amount of the most slowly burning material available into the fireplace or pits before leaving camp or turning in for an all-night sleep.

All the meat we dried was carefully sacked, then hauled to the railroad and shipped, most of it being sent to Cheyenne then forwarded to eastern cities by Colonel Jones on orders from his numerous acquaintances. Meat thus prepared brought a good price.

We certainly led a busy life, but it brought its rewards. We always had a camp appetite, and at night when our camp work was done and we had reloaded our rifle shells for the following day’s shooting, we were undeniably ready for a portion of nature’s sweet restorer. Early rising in a hunter’s camp must be the rule if success is desired. No alarm clock was needed in our camp. We awakened bright and early, refreshed by sleep and the pure mountain air. Never since those old hunting days have I been able so completely to relax and rest out in a few hours…

During my experience as a hunter I made and saved a little over $10,000. Game was plentiful all over Wyoming, and it was impossible for me, during my hunting period to foresee the day when big game of the United States would become as nearly exterminated as it is.

I was brought up to believe that a Nimrod or mighty hunter is as much to be respected as anybody-at least, among those who have the bread and butter problem to deal with in connection with securing the necessities of life. When now I hear old-time hunters spoken of as game butchers or game hogs, I cannot help resenting the accusation. I take pride in knowing that I never was a hide hunter, that I never took pleasure in killing game that I could not use. …Nor was the extermination of big game in the West an unmixed evil. The passing of the buffalo meant a great deal to the civilization of our western ranges. It had more to do with starting the Indians of the Plains on the white man’s road which they are now obliged to travel, than all the forces brought to bear upon them by the United States Army.

In the fall of 1879 Billy Martin, Charlie and I were hunting in the Shirley Basin country in Wyoming. Billy made a trip on the railroad down to Cheyenne. When he returned to camp he brought a number of young English sportsmen with him. Colonel Jones had sent them to our camp in order to give them a good opportunity to get some big game shooting, and also to give us a chance to make a little extra money. These gentlemen proved to be as fine a lot as it was ever my privilege to meet. They were ardent young sportsmen-Oxford men, athletic, full of life, and with all the education necessary to make anyone fully enjoy living close to Mother Nature. They remained in our camp about a month, and returned to England fully loaded with both trophies of the chase and, I think, the feeling that they had a most enjoyable time in the American Rockies…

Late in the fall off 1880 I guided a party of Englishmen on a hunting trip into the Big Horn Mountains of Wyoming. We found plenty of game-elk, buffalo, deer and mountain sheep being there in abundance. Bear also were unusually plentiful, and we had some great sport hunting them.

One morning I started out with two of the party on a bear hunt. It was their first hunt and they had never seen a bear in its wild state. As still-hunting a bear usually requires the utmost skill, I had little hope of success especially as the heavy hobnailed shoes worn by the Englishmen made so much noise against the rocks that I was sure we should not be able to get within gunshot of a bear. When we reached the place where I knew there was a good bear ground, I instructed the men to move in line with me, very slowly and carefully through the thick timber, to keep in sight of me, and also, if they saw any animal to beckon me to them.

When we had moved along cautiously in this manner for perhaps a quarter of a mile, one of the Englishmen motioned me to come to him. When I reached his side, he said that he had seen what he thought was a hog enter a little thicket about a hundred yards distant. Knowing that there was not a hog within a hundred miles of us, I was sure he had seen a bear. Looking the ground over carefully, I could see where we could get to a low, rocky point of land that overlooked the thicket into which the strange animal had gone. Backing away slowly until we were out of sight, we slipped around to the point. Reaching there I peered over into the thicket. In a few minutes, I saw a bear within fifty yards of me. He was digging into the ground after some food, and as I observed that he was not alarmed, I watched him several minutes.

Suddenly I thought I saw something move in a clump of brush a short distance from the bear. Changing my position a few inches and watching the place, I caught sight of a very large silver-tip grizzly lying down. Just as I made this discovery, to my astonishment three more bears put in an appearance. They slouched up to the bear that was digging in the ground, and he snarled at the newcomers as if warning them not to disturb him in his efforts to secure food. I motioned for my companions to slip up beside me, and they soon had a view of the bears.

The Englishmen were armed with double-barreled express rifles of heavy bore. I whispered to them that I would shoot the big bear which was lying down, and that the moment I fired, they were to open up on any of the others that were in good positions for shooting. I shot the big fellow and at the report of my rifle he tried to rise, screaming with pain and rage. The one of the bears which was nearest my victim immediately sprang upon the wounded animal and began to bite him. The Englishmen began shooting at once, but the bears instead of trying to escape sprang at each other like demons, fighting and growling savagely. In less than a minute those four bears were merged into one struggling heap, into which we poured shot after shot. The big fellow that I had shot first was out of the battle entirely.

Presently the smallest animal broke away from the others and ran about fifty yards as fast as he could streak it. Climbing up on a fallen log he rose on his hind legs and stood looking back at the battle which was still raging with unabated fury. He offered a beautiful mark. I shot him through the heart and he dropped off the log with a yell.

One after another the remaining bears went down under our rain of bullets, each hit not less than ten or twelve times. It was an exciting scene. My English friends were greatly elated and I myself had witnessed such a sight as I never would have dreamed could be. Very seldom are five bears found together by a hunter, and their reason for flying at each other in such a savage manner, paying no attention whatever either to the reports of our rifles or to ourselves was inexplicable.

When we packed the hides of those five silver-tip grizzlies back to camp that evening, we certainly had something to talk about.

(Cook next described making a deal to get a bighorn sheep for the UPRR Agent in Cheyenne if the latter would arrange passage for Cook’s hunting party 100 miles west to Carbon Station on the UPRR for a hunt at 11,156’ high Elk Mountain.)

He therefore shipped our guns, bedding, snowshoes, and other effects to Carbon, also securing roundtrip transportation for us. When we reached Elk Mountain and I endeavored to fulfill my promise, I found that the sheep had all left that part of the mountains, and that as I had expected it would hardly be possible to ship…the desired mutton. There was nothing left to shoot but antelope and deer. I felt exceedingly sorry for my friend the express agent.

One day I happened to kill one of the fattest antelope I had ever seen. It was a barren doe-the choicest of all antelope meat. I dressed it nicely, being careful to remove all antelope hair from the meat. I then sawed the legs off short, so that the size of the leg bone would not serve as a give-away, after which I sacked it very carefully and shipped it to him…

When we packed up and headed for Cheyenne, I dreaded meeting the express agent, as I had not heard from him regarding the ‘mountain sheep’ I had shipped him. As we stepped from the train he was the first I saw. He came running up and gave us all a good handshake. I could not look him in the face, but Bergersen innocently inquired how he liked the sheep.

“Well boys”, was his hearty response, “that was just great! My friends all said that was the finest meat they ever tasted in their lives.” He then said that people could talk to him about elk meat, antelope, or deer, but in his estimation mountain sheep was the best meat on earth, and not to be mentioned in the same breath with any other kind of wild game. “I have lived here a long time,” he added, “and eaten all kinds of game until I can tell by the taste just what kind of meat it is, but believe me, nothing can compare with that mountain sheep you sent me, and I shall always remember it.”

This was so rich, and was announced in such a convincing and sincere manner, that he was not informed of the trick we had perpetrated on him. Nor did we request him to change his opinion regarding the qualities of mountain sheep meat.

Late one fall when I was hunting in the mountains south of the Shirley Basin…there came a very heavy fall of snow covering the ground to a depth of eighteen inches. The game in the mountains seemed instinctively able to tell when, to prevent being trapped by deep snows, it was time to leave the high ranges and seek a lower level where the snowfall had not been so heavy. We could see signs everywhere about us that the game was moving to the lower feeding grounds. We therefore prepared to break camp and follow.

A few days prior to this heavy snow fall we had killed three or four elk high up in the mountains. We had dressed them out, quartered them, hung the meat up in trees and left it until we could return with pack horses and carry it to camp. Not wishing to leave the meat, Billy Martin and I took some pack horses and a man whom we had hired and started through the deep snow up into the mountains. We had much trouble breaking a trail to the spot where we had left the meat. When we reached the place, we were somewhat surprised to discover that an immense bear had been having a feast on the elk meat. We had hung the hind quarters on stubs of limbs of big pine trees and the bear had stood on his hind legs and reaching as high as possible had stripped off the fat and kidneys and shredded a good deal of the best of our meat. What he did not eat he had playfully or maliciously left lying about. Thinking that the season had arrived when bears would all be in their dens taking their winter sleep, we had had no thought of a bear hunt when we started out after the elk meat. But here was the chance of getting the largest bear which we had ever seen sign of in the Shirley Basin country. Martin and I talked the matter over, finally concluding that as there was some of the elk meat which the bear had not spoiled, we had better send the man back to camp with it while we tried to kill the pesky varmint that had tampered with our meat cache. We carried some of the elk meat along with us in case the chase should prove to be a long one.

It was not a difficult trail to follow. The big fellow had left a plain record through the deep soft snow. We had of course no thought of finding the bear anywhere in the vicinity of the spot where he had eaten his last meal. After we had followed the trail about two hundred yards it made a sharp turn doubling back almost to the starting point, then off led off in another direction. We cut across this bend in the trail and followed cautiously along for perhaps another hundred yards. Finally, I saw where the bear had climbed over a big pine log. Mounting the log I was startled to note that the trail had come to an end! Within six feet of me grew a cluster of young pines. Looking closely down into them I could see a big bunch of hair. Old Bruin was taking a nap! Probably the feast of which he had so recently partaken made him sleep more soundly than usual.

The bear’s awakening was a rude one. My partner Billy was behind me but a step or two as I mounted the log over which the bear’s trail led. The instant I saw that things would soon happen I made sign to Billy to look out for squalls. Then I took aim for the center of that big ball of hair and pulled the trigger of my .40-90 Sharps rifle, immediately jumping back off the log.

The next instant I both saw and heard something. The great head and a large portion of the front end of a huge grizzly loomed up in very plain sight from the opposite side of that log. I was aware that a bear could, on occasions, utter fearsome screams; but that old fellow, as he rose up out of his bed in the pines to see what had dared sting, smoke and so rudely disturb his slumbers, gave vent to the most awful sounds I had ever heard. At that short range, he looked very tall and very wide to me, and the expression on his face was far from pleasant.

Things were now happening rapidly. No sooner had the bear exposed his head and body, with his forelegs all set for smashing an enemy, than Billy sent a bullet through his heart. This was too much lead, and down went Bruin. The man with the pack animals heard the shots and came back to us. We took our bear to camp. When we dressed him we found that our bullets had both passed through him not half an inch apart. Billy had shot to kill. I however could not see what part of the bear I was shooting at. As I now look back to that affair I can see where I might have really started a rough-house with that bear.

We shipped the hide and carcass to Cheyenne. One of our customers, Mr. Dan Ullman who conducted a meat market there at that time, sold both meat and hide for us. The latter brought $50, as it was an exceptionally large and fine specimen, classified as a silver-tip grizzly. It was on exhibition in Cheyenne at the Ullman market for some time….

Even elk hunting during the days when great bands of elk could be found in many of the mountain ranges of Wyoming, had its occasional elements of danger. A wounded bull elk might turn on the hunter and do him great injury, especially if the animal’s horns were grown and in fighting condition. Any buck of the deer families, when wounded, may become a most desperate warrior. I never took many chances when dealing with wounded animals, but on one or two occasions I had rather exciting experiences with them.

One day when I was hunting elk with Billy Martin we shot down six from a band found in the pine timber on a mountain south of old Fort Caspar. One old bull with an exceptionally large set of horns had dropped so suddenly in his tracks that we thought a bullet had broken his neck. Going to the spot where he lay we leaned our rifles against a tree some twenty feet away and made preparations to dress the game. After using my whetstone a few minutes, I picked up one of the forelegs of the big bull to add a few finishing touches to the edge of my knife by stropping it on his hoof-a trick I had learned from the Mexicans in the jungles of Texas.

Hardly had I started in to strop my knife on his hoof when the elk drew a deep breath and started to spring to his feet. He had only been grazed by the bullet, which had passed through the top of his neck. He had been badly stunned from the shock, but his recovery, when it came, was equally sudden and thorough.

I hung to the bull’s foreleg, holding it up so he could not get his forefeet under him, In some manner he was successful in giving me a kick in the elbow, which caused me to lose my hold and I fell across his neck. Grabbing hold of the horn farthest from the ground I managed to scramble over and get my feet on his other horn, hoping thus to be able to hold his head to the ground. This was my first and only experience at bull-dogging an elk.

While I was having my troubles at the front, Billy had rushed in, in an endeavor to get hold of the flank of the bull, trusting that he might thus be able to keep him down until I could take advantage of a lull in the proceedings and draw my knife across the animal’s throat. The kick on my elbow had sent my knife to a distance far beyond my reach, but Billy had not noticed that detail. By some manner of means the bull got his hind legs into action and Billy, according to his own story was kicked to a distance of bout fifteen feet, landing on his back close to the guns. Scrambling to his feet, he grabbed his rifle and taking advantage of a moment when he could shoot without danger of hitting me, put a stop to that bull’s struggles.

I was not sorry when that scrimmage came to an end. I had a bloody nose and black eye to care for, the results of a few whacks about the head and face from the prongs of the elk’s horns. My clothes were pretty well stripped off, also some skin.

Thus, ends Cook’s entertaining account of his hunting trips, although he continued to hunt for the UPRR and to guide English sportsmen into the Big Horns until the fall of 1882 when he moved to southwestern New Mexico. There he established a ranch, fought the Apache and eventually bought the Agate Springs ranch in western Nebraska. His story has been of particular interest to me personally because I lived in Laramie, WY, from June 1980 to December 1983. While there I shot a massive 7x7 nine-year old bull elk, killed mule deer and antelope near Elk Mountain, harvested a fork horn Mule deer with a Sharps Business rifle that lettered to Brown & Manzanaris at El Moro, Colorado, owned a Sharps .45-110 that lettered to Carbon Station and a Sharps .45-110 with “P. Bergersen Cheyenne” stamped on the barrel, conducted archaeological surveys in the Big Horn Mountains, Shirley Basin and the Powder River Basin and lived in a tent for eleven summers from 1974 to 1985 while supervising a dig in the Big Horns. Alas, I was only a few mortgage payments short of being able to purchase Cook’s Deluxe 1873 Winchester, caliber .22 Short, that he had won in a contest, purportedly shooting against Doc Carver. His autobiography is devoid of any mention of it, but the dealer who offered it to me claimed to have gotten it and the photo from one of Cook’s descendants.

Black Powder Cartridge News readers may find Cook’s full autobiography under the title FIFTY YEARS ON THE OLD FRONTIER, Yale University Press, 1923. They were a very full and fascinating 50 years indeed.