The two carbines used in these tests.

Colt’s revolving rifles were introduced prior to the Civil War and were utilized in combat, most notably by Berdan’s Sharpshooters. However, early on in that war, they converted to using Sharp’s Infantry breech loading rifles utilizing a paper cartridge with a separate cap. Remington, who had a very successful line of percussion revolvers, introduced a “Revolving Rifle” based on the action of their revolver in 1865. Uberti currently makes a replica of the Remington revolving rifle in .44 percussion with an 18-inch barrel. Conversion cylinders, chambered for the 45 Colt cartridge in the Uberti Remington-type revolvers, also fit this revolving carbine. A comparison will be made between the performance of this replica revolving carbine and a Marlin Model 1894 Cowboy Competition Carbine in 45 Colt with a 20-inch barrel.

There is a paucity of information on the Remington revolving rifles available in the literature or on line. The best source of information is an article by Mike Strietbeck, which was published in the Remington Society of America Journal for the second quarter of 2007, and is available on the RSA website.

The Revolving Carbine with both cylinders.

According to Mr. Strietbeck’s article,

A Study of Remington Revolving Rifles, the revolving rifles were introduced in 1865, and produced through 1878. He believes that no more than 800 were produced. These rifles were originally available in six-shot .36 percussion and six-shot .44 percussion. Later in the 1870s, they became available in factory conversions in six-shot 38 Long rimfire and five-shot 46 Long rimfire. Generally, in this time frame, the .44 percussion revolver (revolving pistol) factory conversions had five-shot cylinders in 46 Short rimfire. The 46 Short was generally loaded with a 227/230 grain bullet and 20 to 26 grains of black powder. The 46 Long was loaded with a 305-grain bullet and 35 grains of powder or a 300-grain bullet and 40 grains of powder depending on the manufacturer. The article also shows one 45 Colt conversion, presumably not a factory conversion.

Close up of the breech area of the revolving carbine.

According to the article, the revolving rifle had a different frame with a longer cylinder than the revolver. Checking several Remington-type replica revolvers by both Pietta and Uberti, the revolver cylinders are a few thousandths of an inch over two inches. The article gives the cylinder length of the .44 revolving rifle at 23⁄16 inches (2.1875 inch). Measuring the cylinder of the Uberti Replica Revolving Carbine shows a chamber volume of .208 cubic inches. Assuming the same diameter chamber on a cylinder 3⁄16 of an inch longer would indicate a chamber volume of .238 cubic inches. This is about a 14.5 percent in volume and would translate into a black powder charge increase of about five grains. An ad reproduced in the article shows the “Revolving Breech Rifles” to carry an elongated ball of 30 to the pound or round ball weighing 48 to the pound. This translates to a conical bullet of 233 grains or a round ball of 146 grains. The original Remington rifles are found with barrels between 18 and 30 inches. The advertised lengths were 24, 26 and 28 inches, the Uberti Revolving Carbine has an 18-inch barrel, which, when combined with a two-inch long cylinder gives an effective length (barrel plus chamber) of 20 inches. This makes for a good comparison with the 20-inch barrel of the Marlin, which includes the chamber, as the expansion ratio is about the same. Thus, most of the difference in velocity between the two firearms is due to gas loss at the barrel/cylinder gap. Having both percussion and conversion cylinders for the Revolving Carbine allows for a comparison between the two. An R&D conversion cylinder of the capping-plate type with individual firing pins for each chamber was used on the revolving carbine.

The conversion cylinder in situ.

In an ad reproduced in the article, the weight of the “Remington Revolving Breech Rifle” is given as six pounds. The Uberti Revolving Carbine weighs (empty) with the conversion cylinder, four pounds 3.6 ounces. The Marlin 1894 Cowboy competition Carbine (empty) weighs six pounds, 4.4 ounces. The Uberti, with a 250-grain bullet and 40 grains of FFg, thumped the shoulder with authority when firing, due to its curved brass butt plate.

The original Remington revolving rifles were generally equipped with an open rear and a blade front sight; the Uberti carbine is similarly equipped. The Marlin has a Lyman aperture rear sight with a gold bead front sight. Due to the short sight radius, the front sights on both the Uberti and the Marlin were fuzzy. I have often speculated that the reason that long barrels were popular in the black powder era was that as people aged, they could see the front sights better on the longer barrels.

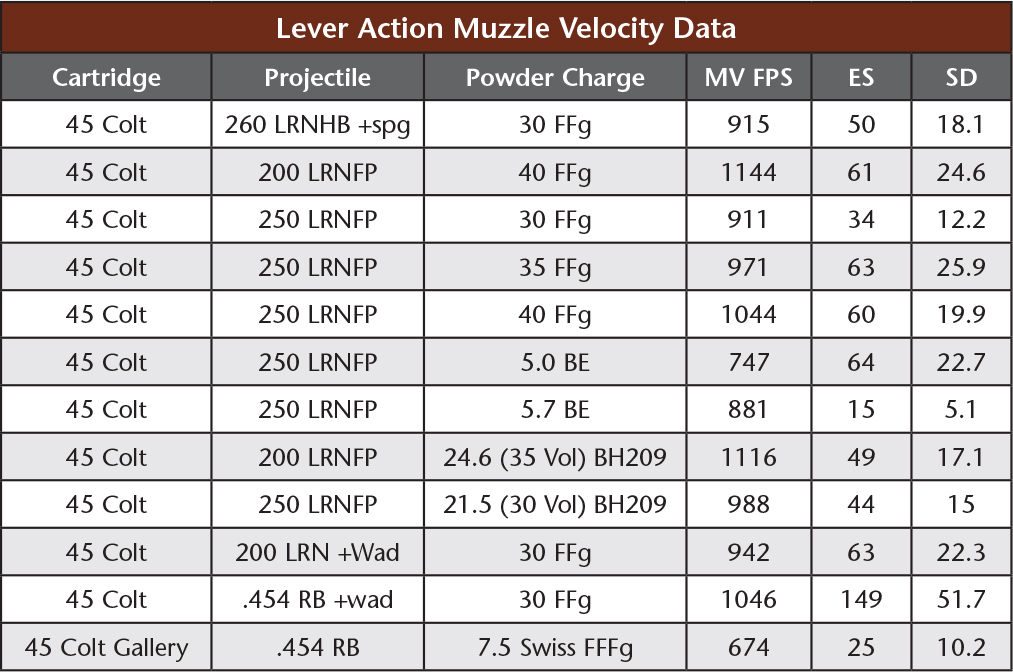

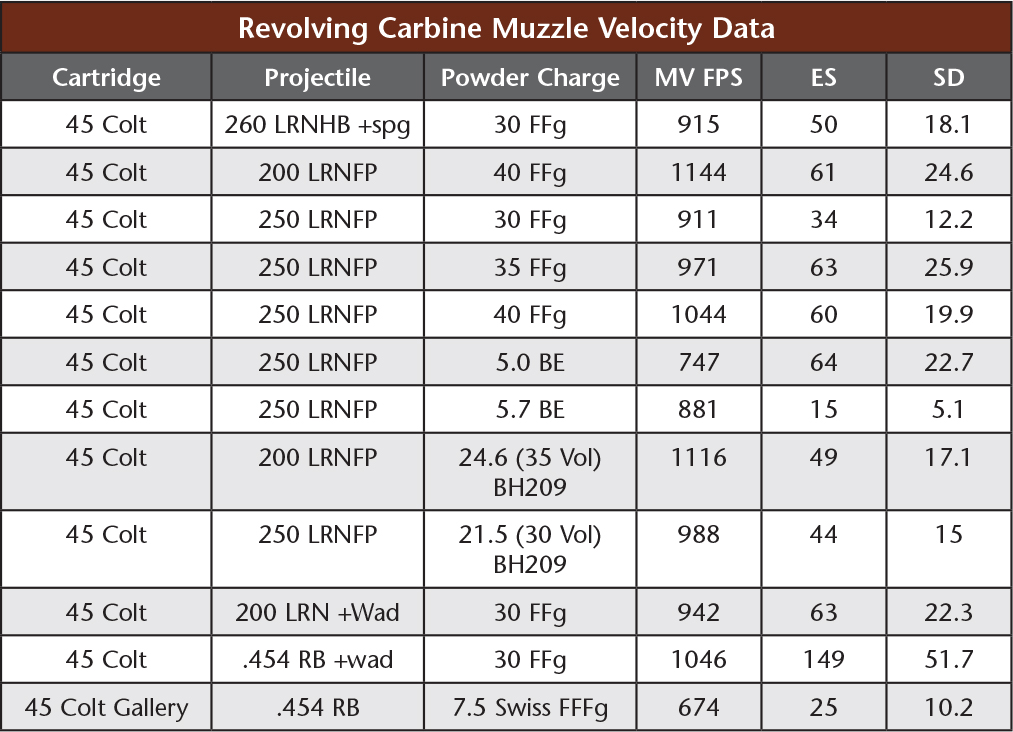

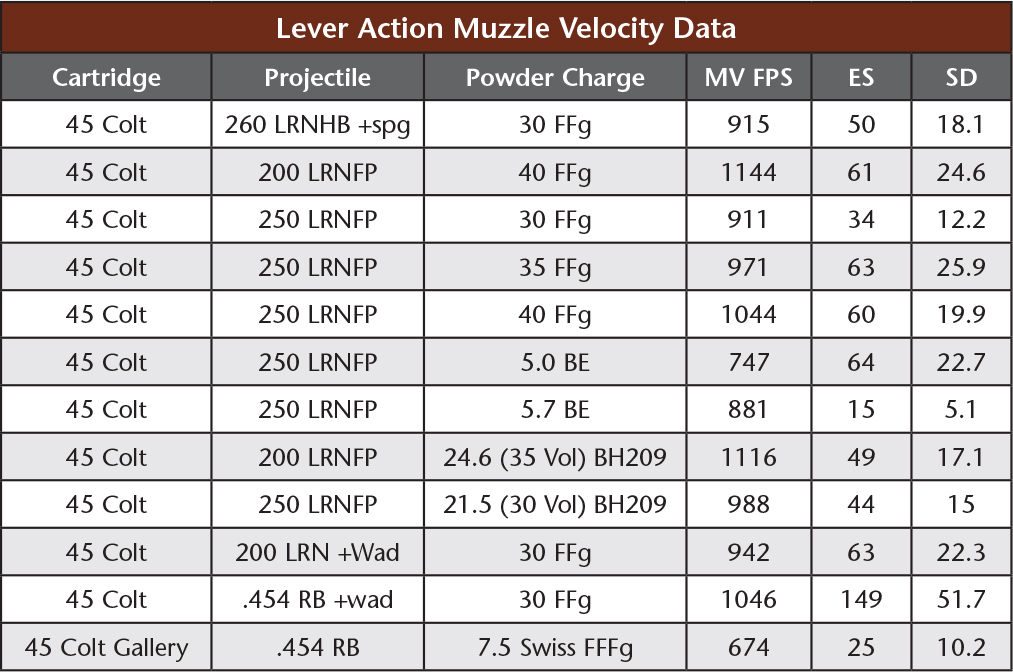

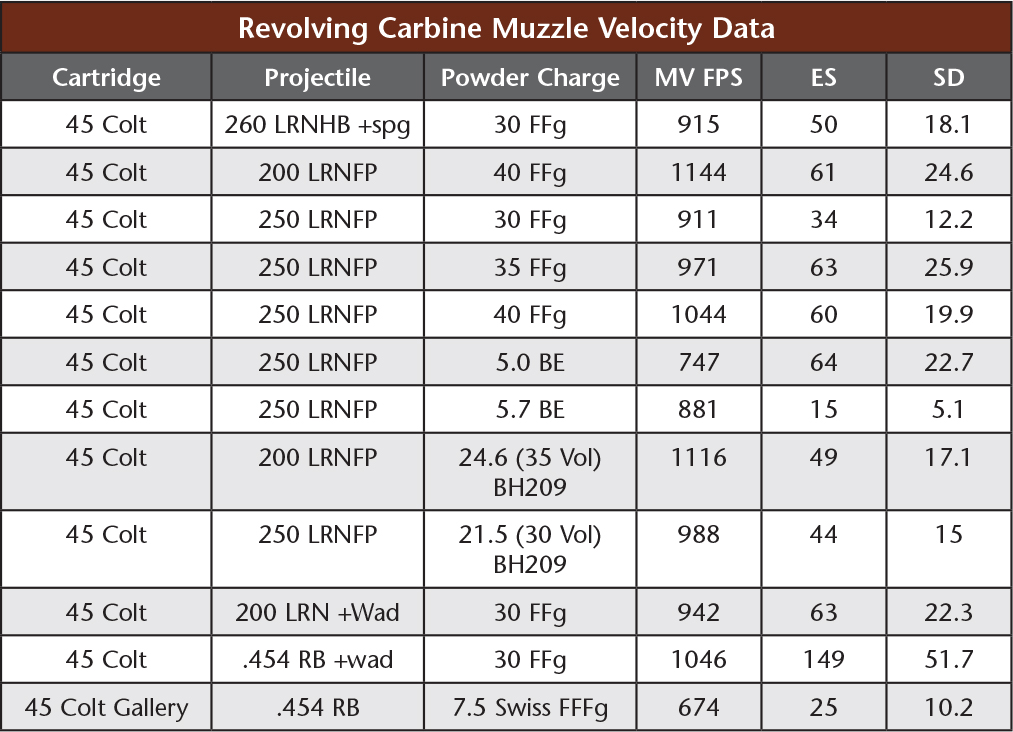

Various sources give the standard load for the .44 percussion revolver as around 30 grains of powder and a conical bullet of around 216 to 218 grains. There were a variety of more or less standard black powder loads available for the 45 Colt cartridge in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as well as smokeless and semi-smokeless powder loads. Goex 2Fg black powder was used in cartridge loads with the exception of Swiss 3Fg being used in the gallery loads. Both Goex 2Fg and 3Fg were used in the percussion cylinder. In some cartridge loads, the use of a black powder compression die was required to get the desired charge in the case and seat the bullet normally. Semi-smokeless powder was available from the 1890s, to World War II. To my knowledge it has not been manufactured since then. Black Horn 209 (BH209) is a black powder substitute available today, primarily for use in in-line muzzleloaders and metallic cartridges. It somewhat fills the niche that semi-smokeless did in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Two loads of it were tested in both the revolving carbine and the Marlin. Two common early factory duplication loads of Bullseye were also tested for comparison in the Marlin. Smokeless loads were not fired in the Uberti carbine with the conversion cylinder, as the frame has only black powder proof. Pre-lubricated felt wads from the Thompson Bullet Lube Co. were used in the percussion cylinder and in selected cartridge loads.

Note that the left hand is behind the barrel/cylinder gap.

Chain firing or the firing of multiple chambers from flash-over on a percussion revolver or revolving carbine is always an issue. I have never had multiple chambers discharge when a felt or card wad was used between the powder and the ball but I have had them when no wad was used. With a revolving carbine, the supporting hand should never be in front of the cylinder. With self-contained metallic cartridges, multiple discharges are not an issue. However, considerable gas and burning particles are blown from the barrel/cylinder gap. When shooting off the sand bag, the back of my left hand was covered with residue. Because of the ejecta from the barrel/cylinder gap, the revolving carbine could not be supported directly on the bag; I made a fist and rested the trigger guard on the fist. The Doppler radar unit was located adjacent to the bag for recording velocities and when I finished it had to be cleaned of the residue that was deposited on it. When firing the revolving carbine offhand and off the bag, gas wash and impacting particulate matter could be felt on my left cheek. It is disconcerting to have up to 40 grains of black powder go off three or four inches in front of your face. The percussion cap adds to this effect when the percussion cylinder is used. Wear eye protection!

The conversion cylinder showing its rebated rim recesses. Because of this, 45 S&W cartridges would not fit as their rim is too large to enter the rim recesses.

The barrel of the Uberti carbine was slugged and found to be .455 in the grooves. It is larger than most percussion revolver barrels that I have slugged which run more like .448 to .451. The percussion cylinder mouths ran .448/449 and the conversion cylinder mouths measured .452/.454. This is not an ideal combination where the barrel has a larger diameter than the cylinder mouths. The question then became, will black powder and soft bullets bump up into the rifling of the revolving carbine? The barrel of the Marlin was not slugged.

In the revolving carbine, R-P 45 Colt (1.285-inch case length/small rim), cut-off R-P 45 Colt Government (1.1-inch/small rim) and Starline 45 Cowboy Special (CB Spl 0.9-inch/small rim) were used. The 45 S&W case (1.1-inch/large rim) would not fit the conversion cylinder chambers as those have rebated rim recesses that were too small to allow the 45 S&W to fully enter the chamber and seat the capping plate with its firing pins. Only 45 Colt (1.285-inch/small rim) cases were used in the Marlin to insure feeding and ejection. Gallery cartridges were single-fed into the Marlin.

Notice the cloud of smoke around the rear of the revolving carbine and the smoke and flame issuing from the muzzle. Firing this weapon is like having a firecracker go off four inches in front of your nose.

From Missouri Bullet Company were procured 200 and 250-grain cast round-nose, flat-point bullets, sized to .452 and lubricated with Thompson PS lube. These bullets have a BHN of 12 and are intended for Cowboy Action loads. The 250-grain bullets used in the smokeless loads were Remington factory bullets #22897. The 225-grain round-nose, flat-point bullets were produced by the now defunct Mid-Kansas Cast Bullet Co. and were in their “Cowboy Action alloy” which is soft and designed to obturate at low pressure. They measured .452 and were lubricated with Thompson PS lube. The 260-grain round-nose, hollow-base bullets were from Bear Creek Supply and intended for use in the .455 Webley. They were .454 in diameter, swaged and hardness tested at around eight to nine BHN. The hollow base was filled with SPG Lube before loading. Round balls were pure lead and were the .451 Hornady #6060 and .454 #6070. These round balls were loaded un-lubricated into the percussion cylinder and when loaded into a metallic cartridge case, were tumbled lubed with Lee Liquid Alox. Only .454 round balls were loaded in metallic cartridges. Federal #155 primers were used with black powder and BH209. The conicals used in the percussion cylinder were pure lead and from a Lee 450-200-1R mould. The grooves on them were filled with SPG Lube (by hand) before loading. Federal #150 primers were used with smokeless and Remington #10 caps on the percussion cylinder. Velocity and accuracy testing was done with six-shot groups in both firearms and muzzle velocity was determined by Doppler radar. The bore was usually swabbed after each six-shot string and accuracy was tested at 25 yards.

The Bear Creek 260 grain LRNHB with and without SPG in its base.

Accuracy was in some ways better than I expected and worse in others. The soft bullets did indeed bump up to obturate in the Uberti barrel. The biggest problem with black power loads was that the first three bullets would usually cut each other on the target and the last three would be flyers. I attribute this to inadequate quantity of lubrication. The fouling was caking up after the third shot. The bullets were all well made and the lube grooves were full. These bullets were designed for use with smokeless powder and the quantity of lube that would fill the grooves was too small to keep the fouling soft after the third shot. The round balls did not seem to suffer this as much. They shot well in both firearms in both gallery and full-charge loads. There were accurate enough to take small game like rabbits or squirrels at modest distances.

The smokeless loads did well in the Marlin and the BH209 loads did well in both firearms. The black powder loads with the 260-grain LRNHB filled with SPG Lube also did well in both guns. When fired in 10-shot groups, this load ran 1.75 inches in the Marlin and the first six in the Uberti grouped similarly, but would open up with the final four shots. The Uberti was more sensitive to black powder fouling, possibly because of the mismatch between the cylinder mouths and the barrel groove diameter. Use of pre-lubricated wads also contributed to reducing issues of powder fouling in both guns. The average of the black powder loads was 2.5 to 3.5 inches for six shots, sometimes opening up to five or six inches as the barrel fouled. Still, I had no trouble making blocks of wood “walk” around the berm when firing off hand at 25 yards with either carbine. No significant difference was seen between the .451 and .454 round balls in the percussion cylinder of the Uberti, either in velocity or accuracy. It should be noted that the performance of the percussion cylinder was significantly improved when using 3Fg versus 2Fg and 2Fg performed better in the cartridge cases. This is attributed to the better ignition from a Large Pistol Magnum primer versus a #10 percussion cap, as well as the crimp on the cartridge case which held the bullet long enough for the propellant to begin burning well.

An “Express” type load was tried in both guns, with a 200-grain bullet and 40 grains of 2Fg. This did increase the velocity over the 250/40-grain load, but the muzzle energies of the 200/40-grain load were still below that of 250/40-grain load. The increase in muzzle velocity would not have flattened the trajectory very much over the effective range of these carbines. If a hollow-point bullet was used, the increase in velocity may help with its expansion. There were “Express” type loads available for the 38/40 and 44/40 WCF cartridges that used the 40-grain charge with a lighter hollow-point bullet. Black powder is almost always more efficient, in terms of muzzle energy per grain weight of power, with heavier bullets than lighter bullets. The main advantage to the lighter bullets, in a small cartridge, is a reduction in recoil. The increase in muzzle velocity between the 250/40-grain and the 200/40-grain loads were three percent in the revolving carbine and 10 percent in the Marlin. The average increase in muzzle velocity between two guns, for all the loads fired in both guns, was 8.9 percent in favor of the Marlin.

The main competition for the revolving carbine in the 1865 to 1879, time frame was the Henry, the Winchester 1866 and 1873, and to a lesser extent the 1876 lever actions, plus the Spencer rifle. The Remington revolving rifle in either .44 Percussion or 46 Long Rimfire was marginally more powerful than rifles taking the 44 Henry rimfire cartridge or the 44 WCF cartridge, but less powerful than the Spencer or the 1876 Winchester. The biggest disadvantage to the revolving carbine is that it’s like a firecracker going off in front of your face. The lever actions, especially with the side-loading gate, were easier and faster to load. Rapidity of action is also in favor of the lever action as it cycles and reloads faster. In a side-by-side comparison, the muzzle velocity and energy were greater with the lever action. The advantages of the lever actions outweighed the marginal extra power of the revolving rifle. After these firing tests, it’s no surprise that the revolving carbine was not a commercial success and the lever action carbine was.