Accuracy Test Part VII

“Best Quality” Sharps Linen Cartridges

feature By: William P. Mapoles & Cartridge Developer - Michael Murray | December, 21

THE HISTORY

Before the American Civil War, the U.S. Dragoons would sometimes find two or three broken Sharps paper cartridges in their cartridge boxes at each halt. This was caused by the weak design of the cartridges, the rectangular tin compartments in the box, and the bouncing around while on horseback. When their paper ammunition broke open, it made a real mess with the powder sticking to the lube on the other cartridges. Additionally, they could ill afford to waste that much ammunition, especially on long patrols, because they typically only carried 20-to-40 rounds per man. Clearly, there was a big need for a more durable cartridge that could withstand rough handling, so the Sharps company introduced the tougher linen cartridge about 1859. In 1861, the military redesigned the cavalry cartridge box, which also helped tremendously, with a separate hole inside for each of the 20 rounds.

The Confederate army, lacking anything better, stuck with paper cartridges throughout the war. Nathan Bedford Forrest, the prominent Confederate army general and cavalry tactician, had the highest respect for the Sharps carbine. He once remarked that unlike most of the other Federal carbines, the Sharps was still dangerous out to 800 yards. He was certainly one to know! During the first part of the war, there were simply not enough carbines to completely arm the Union Army Cavalry Corps, and many Yanks went into battle with only a pistol and saber, requiring them to get in very close to the Rebels. They ran up against Confederate Army Cavalry troopers carrying weapons such as double-barreled shotguns, “Mississippi” rifles, Hall’s carbines, rifled-muskets, and hunting rifles; with disastrous results. As the war progressed, the Union cavalry got almost a full complement of breechloading carbines, and they were then able to shoot at greater distances with more accuracy and speed to try to keep the Rebels at bay. In the end, it was a war of attrition as we know. The top four Union carbines, in order of the highest numbers actually used during the war were the Sharps (80,512), Burnside (52,881), Spencer (45,733) and Smith (30,360).

THE LINEN

Why use linen? Simple, it is made of flax, which is stronger than paper and it is very flammable. After examining some original Sharps Company cartridges, we determined that the linen was very closely woven, and it was .005 inch thick. (Cotton bedsheets are about .010-inch thick by comparison.) Our original Sharps Company cartridges were made with two wraps/layers around the mandrel, while other competitors used only one. This made for a stiffer, more durable cartridge. By the way, the linen used in our previous article was .011/.012-inch thick, so we could only use one wrap.

In the interim, we discovered a new, much better linen that we have incorporated into this latest test, namely “architectural drawing linen” (not “architectural parchment,” which is paper). Amazingly, it looks and feels just like the linen used by Sharps and it is the exact same thickness. For many decades, it was used by architects, design engineers, and for city/county plot maps. If you have ever looked at an old county plot map, you have undoubtedly seen it, and it stands up well to many years of rough handling. One side is heavily starched for drawing on, while the other is left almost in its natural state. We discovered that one gentle washing removed the bulk of the heavy starch, but it still left just enough for good rolling and forming properties. Unfortunately, architectural drawing linen isn’t used anymore, because computer graphics have replaced it; however, there is still some to be found in old businesses and on the internet.

We cut the linen to 13⁄8 inch by 35⁄8 inch for two wraps and we made the seam straight like the originals. Do not overlap the seam, but rather cut the linen so that the ends meet each other, making the cartridge wall thickness consistent. We used Elmer’s “Natural” Glue for the seam, and for closing the base of the cartridge with a small circle of .002-inch thick, 100 percent cotton rag paper. The circle was pushed through to the base of the linen tube with a dowel. This made for a correct flatbased cartridge that was not cut off when the breechblock was raised, and it was slightly shorter than the length of the chamber. The same glue was used on the base of the bullet to attach it to the cartridge and the linen was then choked into the bottom grease groove in accordance with the 1864 military specifications.

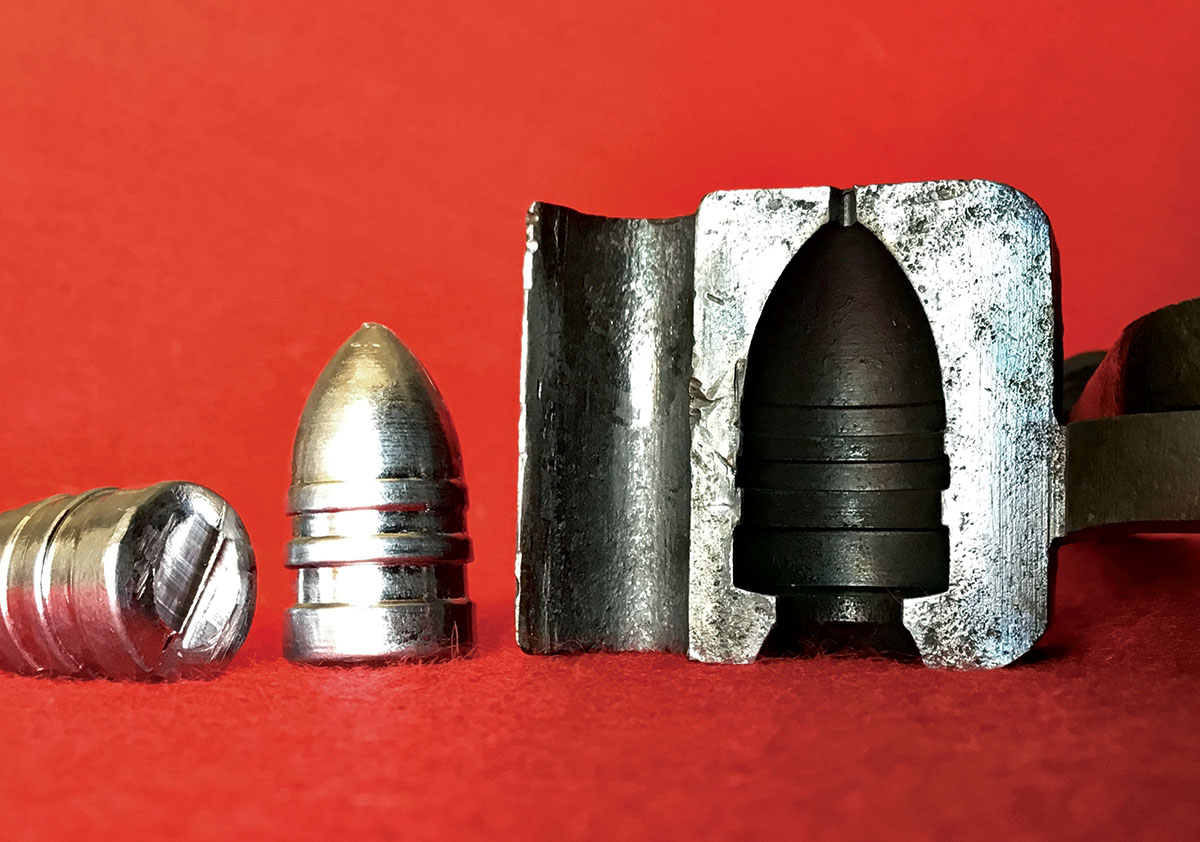

THE BULLET

Very few of the original Sharps Company moulds have survived, because it seems they also worked great for shoeing horses and stringing barbed wire. This mould cavity had no ringtail, nor did it ever have a sprue plate, so the sprue was cut off with the built-in pincers on the front of the mold. This left a raised line of lead across the bottom of the bullet, which meant the bottom was not perfectly flat. However illogical it may seem; I could not tell that this made much of a difference in the accuracy. For example, I tried removing the raised lines completely with a penknife and file, but that didn’t seem to help. Maybe with a longer sight radius and a Vernier tang sight, a shooter could tell a difference on the target, but not with the crude open sights on a military carbine.

Historic Sharps literature has stated that the original bullets weighed 453 grains and that is exactly what this mould threw on average. The bullets were visually sorted for use, but not weighed. Pure lead was used back in the day without the addition of tin, so I stuck with that to be historically correct. The top band of the bullet measured .521 inch, the middle band was .538 inch, and the bottom band was .540 inch. The length of the bullet was .973 inch, not including the sprue pincer ridge on the base. The taper of the bullet was a good match for the taper in the chamber throat (aka: bullet seat). The lube was a mixture of tallow and beeswax, just like the originals.

THE POWDER

In 1864, the Ordnance Department increased the Sharps powder charge from 60 grains of government-issued musket powder to 65 grains. This was to better match the ladder distance numbers stamped on the rear sight. It also resulted in the Sharps having the heaviest powder charge of all Civil War breechloading carbines. A fellow named Peter Schiffers has opened a variety of original Civil War-era cartridges, and has fired the powder through a chronograph with a cap-and-ball revolver. Next, he compared the results with modern powders, and it seems that Swiss 1.5 Fg was the closest match to the velocity of the original “musket powder.” Therefore, I used 65 grains of Swiss 1.5 Fg, poured through a drop tube to make a firmer cartridge, like our original tight Sharps exemplars.

THE CARBINE – AN ORIGINAL NEW MODEL 1863

To get a proper historical comparison, I used a standard issue 1863 Sharps, serial number C,504. The barrel was 22 inches long and the sight radius was 18 inches. The twist was about one turn in 48 inches and the bore was about a 9.7 on a scale of 10. The land-to-land diameter of the barrel was .526 inch, and the groove-to-groove diameter was .534 inch, giving a rifling depth of .004 inch. Interestingly, the base band diameter of the bullet was .006 inch larger than the groove diameter of the gun, which is very often the case with Sharps percussion ammunition. However, the thin rear bullet band and the tapered chamber throat seems to mitigate some of this problem, but don’t overdo it as pressures can rise to dangerous levels. Please also note that on earlier Sharps models, like the Model 1852 and 1853, the groove diameter and rifling depth is often much greater, which means that this bullet used in this test would be too small in diameter for some of these earlier models. Maybe they made the rifling shallower during the Civil War in order to reduce the time it took to rifle a barrel, so they could crank them out faster. Other wartime makers, like with the Smith and Maynard carbines, used very shallow rifling too. In any case, slug the barrel and choose the bullet accordingly. Also, have the gun checked for safety by a competent black powder gunsmith before shooting it.

With respect to the receiver, the gap between the chamber sleeve/bouching and the face of the breechblock was less than one-thousandth of an inch. To be clear, the block would not completely close on my thinnest metal shim stock, which was .001 inch. My guess is that this matches the original factory specification since this carbine shows little evidence of having been shot very often. High-speed photography taken at the moment of ignition showed almost no gas leakage, except from the nipple as one would expect. The nipple was the original issue and had a much larger orifice than modern nipples, which ensured better ignition through the very long flash channel with two 90-degree turns and a blind cleanout screw hole. As a result, there were no hangfires or misfires during the test.

THE ACCURACY TEST

I decided to test these cartridges on paper at both 100 and 200 yards. Further, steel gongs were slammed with great regularity out to 400 yards using this bullet and the ladder sights. All shooting was done over a benchrest with sandbags fore and aft. Five-shot groups were fired and measured from center-to-center of the two widest shots. Between groups, the bore was wiped with one wet and one dry patch, because the accuracy fell off gradually after five shots with these full-power historic loads. Just for fun, I shot one 10-shot group without any cleaning and it was pretty darn good. Remember that cavalry engagements tended to be short, sharp clashes, with relatively few rounds expended, because the primary mission of the cavalry was to conduct reconnaissance. Sure, I could shoot all day without cleaning until the bore looked like a sewer pipe, but that would not tell us very much, except perhaps about the amount and effectiveness of the lube. By the way, these bullets had very little lube on them since the linen is choked into the bottom groove of the bullet, and the top groove is very shallow.

As in my previous tests, I did not shoot oil/fouling shots into the berm. All are included in the group size, because I wanted to determine the historic performance of original guns and loads used in combat. Further, the sights were not perfectly adjusted for 10X target performance, because I was more interested in group size to properly evaluate these new linen cartridges.

The 65 grains of Swiss 1.5 Fg gave an average velocity of exactly 1,000 feet per second (fps) with the 453-grain bullet. The extreme spread for the 10 shots through the chronograph was 45 fps, and the average deviation was 12 fps. People have asked why I use “average deviation” instead of “standard deviation,” and it is simply because I never could remember nor understand the math used to calculate standard deviation. I can only manage to get my head around average deviation, and it seems there isn’t much difference anyway. Nevertheless, these extreme spread and deviation numbers were a bit higher than I expected based on previous tests. I guess this is due to some bullets going through the barrel with small bits of linen, or a ring of linen and glue, still attached to the bottom band of the bullet. However, I have no evidence to suggest that the linen stays on the bullet, as there was none found on the targets or the cardboard backers.

Amazingly, in all cases, there was no burning linen or any significant linen trash left in the bore after firing. That is not to say that it can’t ever happen, it just didn’t happen with these cartridges. As we know, this can be a big problem with paper cartridges, nitrated or not. However, I did notice some flat red speckles stuck to the inside of the chamber, which I guessed to be sulfur. I sometimes get little red sulfur balls inside my muzzleloaders that can clog the nipple, especially with Swiss powder. The good news is that the linen is almost completely disintegrated by the powder blast without any need to impregnate or nitrate the material. We busted that myth in our last article. I scoured the dirt in front of the muzzle for any linen residue, and I found only one tiny piece about a half-inch long and one-eighth inch wide that had adhered to the base of a bullet, as evidenced by the rifling marks left on the linen. No other trash was found, which was pretty remarkable. My theory is that linen is more porous than paper, which allows the powder flame, under great pressure, to better penetrate and consume the fabric. Just hold a piece of linen and a piece of typing paper up to the sun and see for yourself.

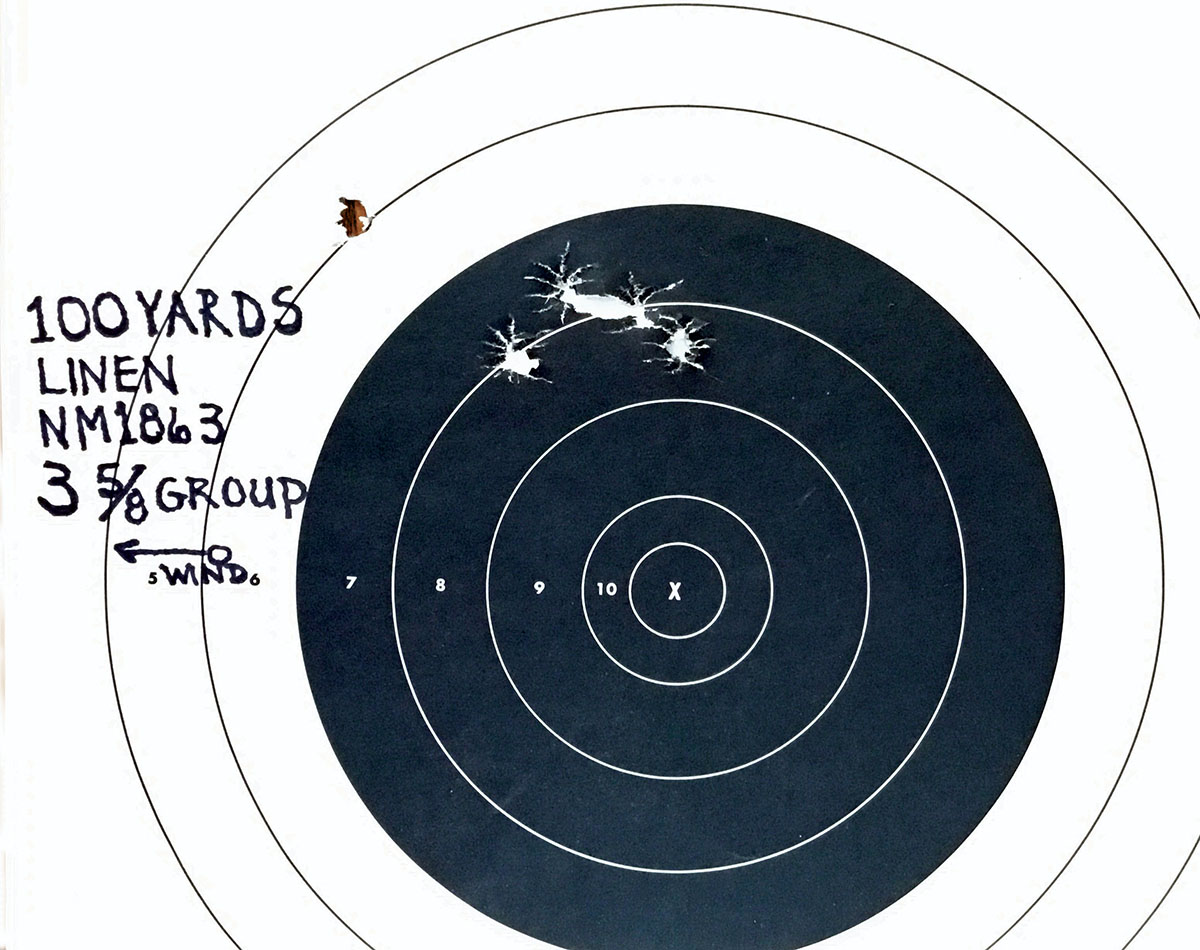

At 100 yards, I shot three, five-shot groups measuring 3.4, 3.63 and 4 inches, for an average of 3.68 inches. Ten consecutive shots came in at 4.6 inches. The wind was running 3-9 miles per hour and I pulled out my hair trying to catch the lulls.

At 200 yards, I shot three, five-shot groups with these bullets measuring 5.88, 6 and 6.75 inches, for an average of 6.21 inches. This is very respectable, given a 7-pound trigger pull, the slow lock-time, and the crude sights. There was almost no wind that day, no glare, and my eyes were working perfectly.

I liked the performance of this particular bullet better than any of the other modern flatbased, non-ringtail designs that I have tried in the past. Plus, when combined with this powder charge, it hit almost dead-on using the distance numbers on the ladder sight. That made shooting it extra fun at long range. An added bonus was that even with the small amount of lube on the bullet, I did not get any leading. Those old guys back in the 1860s really got it right with this bullet design.

RANGE TIPS FOR THE SHARPS

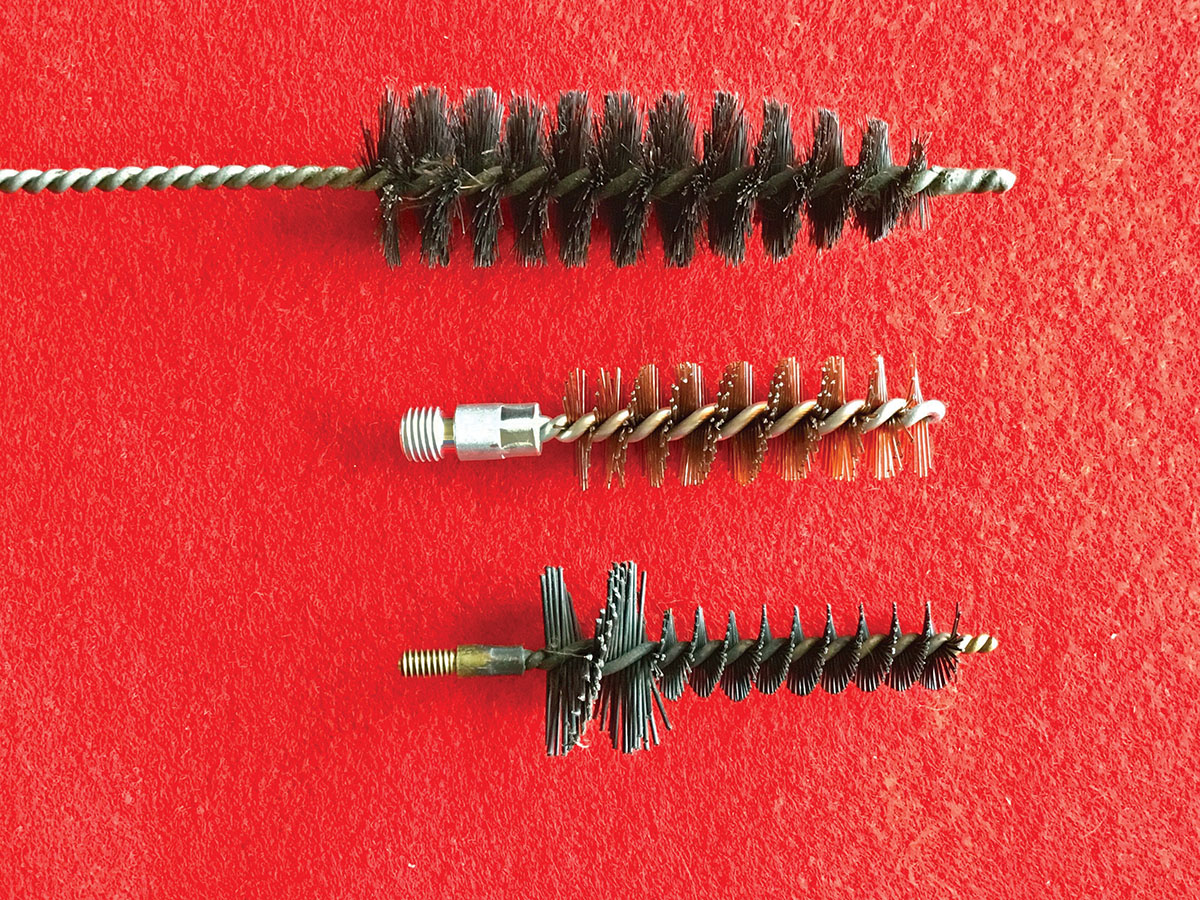

While thinking about the practicality of the original boar bristle brush and leather thong issued to clean the Sharps in the field, I had a blinding flash of the obvious, namely that one could use a modern .54-caliber or 28-gauge boresnake to do the same thing. Plus, they are hand washable. Another good idea was to use PAM frying pan spray to lube the breechblock at the range. Yup, simply take the block out and spray it. PAM adheres to the metal better than any other lightweight lubricants I have tried, it is very heat resistant and is easy to clean. It sounds goofy but it really works. (I didn’t use either of these tips for this test to be historically correct, but I have for plinking.) Before you shoot, regardless of what breechblock lube you use, always bust at least four caps first to completely dry out all the oil from the very complex flash channel. It takes less than a drop to kill a spark. Finally, when you put the cartridge into the chamber, push it all the way forward and wiggle it around a bit with your finger to seat it perfectly centered in the throat.

HUNTING TIPS FOR THE SHARPS

The biggest cause of ignition failures with any percussion gun is oil in the flash channel. I’m sure some greenhorn soldiers actually died as a result of this. Use 91 percent rubbing alcohol, now available at any pharmacy, to degrease the block and chamber the day before the hunt so it can dry completely. If there is any remaining fear of dampness, bust several caps before loading. Beware of oil hiding in the recess in front of the chamber sleeve (aka: bouching), because it could kill some of the powder in your cartridge. To lubricate the breechblock, put a very light coat of thick grease on only the most critical friction points. The less grease, the better. A lightweight oil might run and get into the cartridge base or flash channel – not good when the gun might be left loaded for several days. On very hot days, beware of bullet lube melting and running into the powder.

If it rains, all bets are off, because unfortunately, there is no way to effectively waterproof a percussion Sharps. There is no telling how many cavalry troopers were killed during or after a rain shower while frantically trying get their wet Sharps to shoot. Even a heavy dew would cause fits. Once it gets wet, it is a big chore to dry it out. Obviously, the other three top Union carbines had more water-resistant ammunition. At least with a muzzleloading rifle-musket, one could put a cork/tompion in the muzzle, along with some bullet lube around the base of the cap and nipple and still be combat effective. (Warning – don’t forget to remove the cork when you shoot!)

We have all heard the stories of soldiers in the heat of battle supposedly urinating on their breechblocks to free up a jam, or by pouring water from their canteens onto the blocks to get them unstuck. I have seen several fellows try this by pouring water on their breechblocks; and thereafter, they could not shoot for quite a while, because their guns would not ignite a fresh cartridge. The breechblock had to be removed and the whole breech area completely dried out with rags and with many busted caps. That would take a soldier out of action for quite a while at the risk of his life and he and his comrades would quickly learn to never try that again. Remember, Christian Sharps recommended a few drops of water or some spit on the top of the block for this purpose, but not a full bladder.

CONCLUSION

This is the most accurate cartridge with a flatbased bullet (e.g., non-ringtail) that I have ever tested in a Sharps. The bullet and linen were clearly superior to all others previously tested. Short of shooting several boxes of original cartridges, this is about as close as a shooter could ever come to determining the actual combat accuracy of a Civil War Sharps carbine with linen cartridges. Only a swaged Sharps bullet might be very slightly more accurate than this one that I cast in an original Model 1863 Sharps mould.

So, how does the accuracy of this “best quality” linen cartridge compare to other types of percussion Sharps ammunition? As this point in time, I have written accuracy test articles on the models 1851, 1852, 1853, 1859 and now the 1863. While the accuracy of this flatbased bullet is excellent, it is still slightly less accurate than my ringtail mould, probably because there are times when some linen and glue adhere to the base band of the bullet. However, the linen is clearly the best for durability in shipping and handling, which is exactly what the army wanted back then. In addition, if a shooter doesn’t want to worry so much about the dangers of smoldering pieces of paper in the chamber, then linen is the way to go. (Always look in the chamber after each shot, because a shooter never wants to shove a fresh cartridge into burning chamber residue.)

Next, you might ask what was the most accurate Sharps model of all those tested? Here they are in order, in terms of the smallest 100-yard group averages: (1) the Model 1851 won hands down with an average of 2.63 inches; (2) the Model 1853 was next with 3.18 inches; (3) followed by the Model 1852 with 3.66 inches; (4) the New Model 1863 with 3.68 inches; and (5) the New Model 1859 rifle with 3.88 inches. Of course, there are many cartridge and gun variables in my tests that we could debate, but the bottom line is that all of these rifles group better than most troopers could hold. There is not a bad model in the bunch, and all of them are more accurate than many modern carbines with open sights.

All-in-all, this has been a very fun project and even though percussion cartridges are somewhat time-consuming to make, it is still faster than using brass cases; what with all that annealing, lubing, sizing, expanding, de-lubing, priming, seating and cleaning them. So, get out that percussion Sharps that is rusting away in your safe and spend time with the old gal. Remember this adage, “Don’t just fondle them old guns, SHOOT ‘em.” Plus, we all know that “recoil therapy” is good for you!

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND REFERENCES

–Thanks to Dave Thorn, editor of “The Sharps Collector Report,” for the use of this bullet mould.

–Thanks to Dean Thomas, a leading expert on cartridges from this era, for his kind assistance.

–Roy Marcot, Edward Marron Jr., Ron Paxton, et al., “Sharps Firearms, Volume 1, The Percussion Era,” Northwood Heritage Press, Tucson, AZ, 2019. A truly great book. Few are left, so buy now!

–Peter Schiffers, “Civil War Carbines... Myth vs. Reality,” Mowbray Publishing, Woonsocket, RI, 2008.